One day in early 1950, as Washington reeled from the twin blows of the communist triumph in China and the Soviet Union’s first atomic blast – and as a junior senator from Wisconsin named Joe McCarthy blamed it all on treason – an influential State Department consultant advised that the “threat of international communism” could be countered by employing a comparative U.S. advantage: advertising. “If we can sell every useless article known to man in large quantities,” reasoned banker Robert A. Lovett, one of the original “Wise Men” of postwar foreign policy, “we should be able to sell our very fine story in larger quantities.”

As it happened, a former ad man who fully shared Lovett’s faith in the superiority of American capitalism and democracy, and who had plied his trade not on Madison Avenue but in California, was about to make his mark selling America’s brand in the Cold War. Over the coming decade, authoring, with his own distinctive blend of hard and soft power, two (apparent) foreign policy victories in Southeast Asia – in the Philippines and Vietnam – Edward G. Lansdale would become an espionage icon and a guru of the emerging strategy of counterinsurgency; he was even seen as the inspiration for two major novels (and ensuing films). But in the 1960s, his fortunes, and those of the U.S. aims he promoted, would nosedive – in Cuba and then Vietnam. As a final indignity, in the mid-1970s, he would be hauled before the congressional Church Committee investigating CIA excesses, especially its role in assassination plotting against Fidel Castro; and in a nasty posthumous coda, Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie, “JFK,” would implausibly implicate a sinister Lansdalian stand-in (“General Y”) in the murder of his own president.

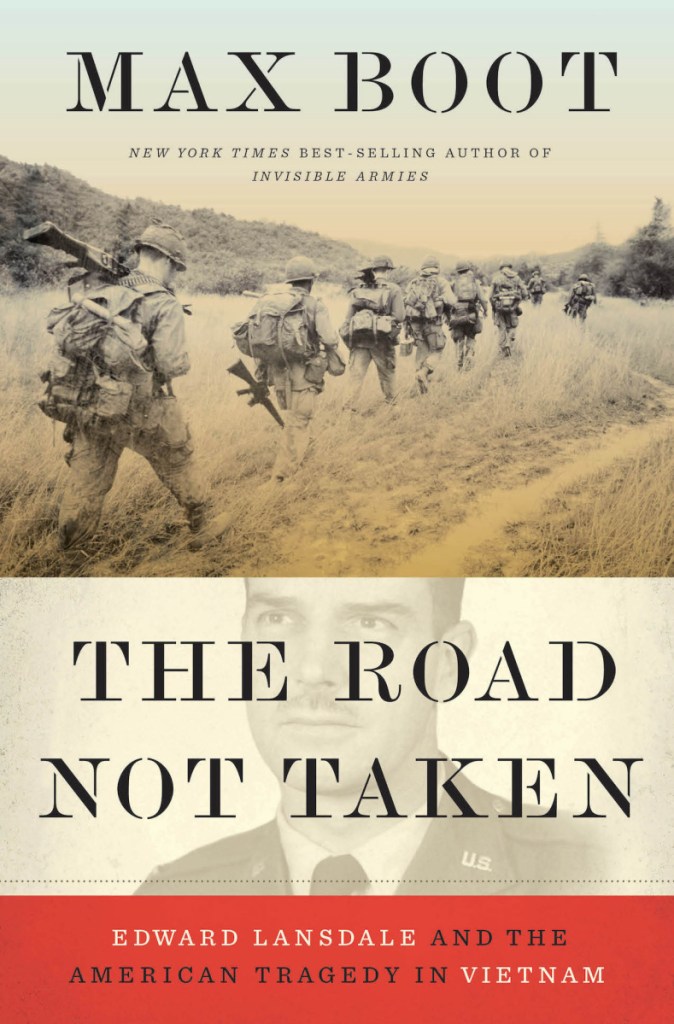

In “The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam,” Max Boot capably and readably tracks the fascinating but ultimately depressing trajectory of this shadowy figure, who, as a murky undercover operative and a literary and cinematic avatar, looms over or lurks behind some of the crucial moments in U.S. foreign policy in the decades following World War II, culminating in its greatest disaster.

Boot’s is not the first biography of this controversial man. Cecil B. Currey’s “The Unquiet American” (1989) provided a fine rendering of the basic life story given the record then available, and Jonathan Nashel’s “Edward Lansdale’s Cold War” (2005) probed its “cultural mythography,” examining popular as well as policy reverberations. Nearly three decades after Currey, Boot taps more recently opened government files and draws on additional family correspondence and interviews that illuminate Lansdale’s career, especially his Philippines and Vietnam missions.

Lansdale, who began his intelligence career during World War II with the Office of Strategic Services (the CIA’s forerunner), went to the Philippines after the Pacific war ended. There he fell in love with both the newly independent country and, as Boot recounts, a Filipina woman, while his wife waited behind in Washington. (Their decades-long, on-again-off-again romance, which, after Lansdale’s first wife died, produced a late second marriage, yielded a vast intimate correspondence that enriches Boot’s narrative.) In the early 1950s, Lansdale helped Philippines leader Ramon Magsaysay crush the communist-inclined Hukbalahap rebellion with a combination of sometimes folksy, personalized psychological warfare, well-aimed propaganda and selective brutality.

Hoping for an encore, CIA Director Allen W. Dulles in 1954 sent Lansdale to Saigon, hoping to prop up a pro-American, anti-communist regime as the United States supplanted the French after their defeat at the hands of Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh. To the surprise of many, including bureaucratic doubters, Lansdale was able to bolster Ngo Dinh Diem’s effective campaign to consolidate control of South Vietnam against sectarian and communist rivals.

By the decade’s end Lansdale had accrued even more mystique from his apparent fictional appearances in two major novels: “The Quiet American” (1955), Graham Greene’s eerily prophetic tale of well-intentioned American moral and political missteps in Vietnam, trapped between communism and colonialism, and “The Ugly American” (1958), by Eugene Burdick and William J. Lederer, a scathing critique of U.S. foreign policy whose thinly disguised Lansdalian hero (counterinsurgency expert Edwin B. Hillandale) struggles to promote American ideals and interests in Southeast Asia against nationalist revolutionaries and diplomatic bunglers. While Currey comments that Greene was “the first author to caricature Lansdale’s real-life exploits,” Boot echoes more recent scholars, such as Nashel and Fredrik Logevall in his Pulitzer Prize-winning “Embers of War,” in agreeing that Greene mostly modeled his ill-fated protagonist, CIA officer Alden Pyle, on other Americans in Saigon. (However, Boot shows, Lansdale did prod writer-director Joseph L. Mankiewicz to give the Hollywood version of Greene’s novel a pro-American, anti-communist spin.) Lansdale’s experience clearly spurred Burdick and Lederer’s novel, as well as (more loosely) Marlon Brando’s role in the 1963 film.

Impressed by “The Ugly American” and intrigued by rumors of an American James Bond, John F. Kennedy hoped Lansdale could repeat his magic and solve one of his most vexing foreign policy woes – not in Southeast Asia (though JFK flirted with naming him ambassador to Saigon) but Cuba, after the April 1961 Bay of Pigs debacle. He put Lansdale in charge of the Operation Mongoose covert ops program against Havana, but it flopped. Nothing worked, including various far-fetched assassination schemes, of which Lansdale later denied awareness (Currey thought he must have known more, but Boot credulously accepts his denials).

All this was prelude to Lansdale’s second major Vietnam mission, at the war’s height in 1965-68, after Diem’s overthrow in late 1963 (when Lansdale was largely sidelined). With a team of advisers, he pressed for political, social and economic reforms to complement anti-communist military operations, but he remained frustrated by the South Vietnamese regime’s inability or unwillingness to effectively pursue those goals, and his own government’s clear priority, embodied by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, on killing the enemy by using overwhelming and sometimes indiscriminate force, rather than winning the sympathies of ordinary Vietnamese. Unable to replicate the effective results or insider influence he had won with Magsaysay in the Philippines, Lansdale became marginalized and left Saigon for the last time in June 1968 “a beaten man,” Boot recounts.

A senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, Boot has written several books on military strategy, focusing on guerilla or small wars and blending history with policy prescriptions. Lately, however, he has been better known for his political persona, proffering foreign policy advice to Republican presidential candidates John McCain, Mitt Romney and Marco Rubio, and popping up frequently on cable news as a “never-Trumper” Republican talking head (or former Republican, since he reports abandoning his party affiliation, re-registering as an independent, the day after Trump’s election).

Boot’s long history of right-leaning politics and his book’s title aroused apprehension, in this reviewer at least, that “The Road Not Taken” might be less a work of historical scholarship than a partisan polemic arguing that the U.S. military plunge into Vietnam was proper, necessary and/or winnable, and could have preserved an anti-communist bastion in Saigon were it not for nefarious Democrats (and inept military commanders) who botched and ultimately sabotaged the American effort. Such arguments have infused some Vietnam tomes popular on the right, from Michael Lind’s “Vietnam: The Necessary War” (1999) to Lewis Sorley’s “A Better War “(1999) to Mark Moyar’s “Triumph Forsaken” (2006).

Boot clearly admires Lansdale, both his idealism and his strategy, and believes, not unreasonably, that the United States and Vietnam might have been better off and that the death tolls from the war – than more than 58,000 Americans and 3 million Vietnamese – would have been far lower had Washington chosen his approach over McNamara’s, which relied on heavy firepower and advanced weaponry to produce the highest possible body count and kill ratio statistics.

However, Boot judiciously refrains from contending that Lansdale’s route would have yielded a materially different outcome. He recognizes that Ho had far more legitimacy and popular appeal, as a nationalist who had fought the French for decades, than the Saigon leaders (whether Diem or the squabbling generals who followed him) and that Vietnam’s basic situation, in important respects, was far less favorable for Lansdale than that in the Philippines had been.

The closest Boot comes to charting an alternate history is when he faults Washington for withdrawing Lansdale from Saigon in late 1956 and failing to “replace his constructive, if not always decisive,” benign influence on Diem, to counter the “paranoid counsel” of his brother Nhu. That failure, he writes, set Vietnam on course to become, within a decade, “a failing state kept alive only with heavy infusions of American blood.”

“Perhaps Lansdale’s achievements could not have lasted in any case,” he hedges, “perhaps Diem would have fallen and Hanoi would have prevailed no matter what – but the course on which Washington had now embarked made failure far more likely and at far higher cost.”

That seems reasonable, but it also seems likely that Lansdale’s “road not taken” would have ultimately led, in Vietnam, to a similar destination. No sale.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.