The rescue of the planet’s protective ozone layer has been hailed as one of the great success stories of modern environmental regulation – but on Monday, an international team of 22 scientists raised doubts about whether ozone is actually recovering as expected across much of the world.

“We’ve detected unexpected decreases in the lower part of the stratospheric ozone layer, and the consequence of this result is that it’s offsetting the recovery in ozone that we had expected to see,” said William Ball, a scientist with the Physical Meteorological Observatory in Davos, Switzerland.

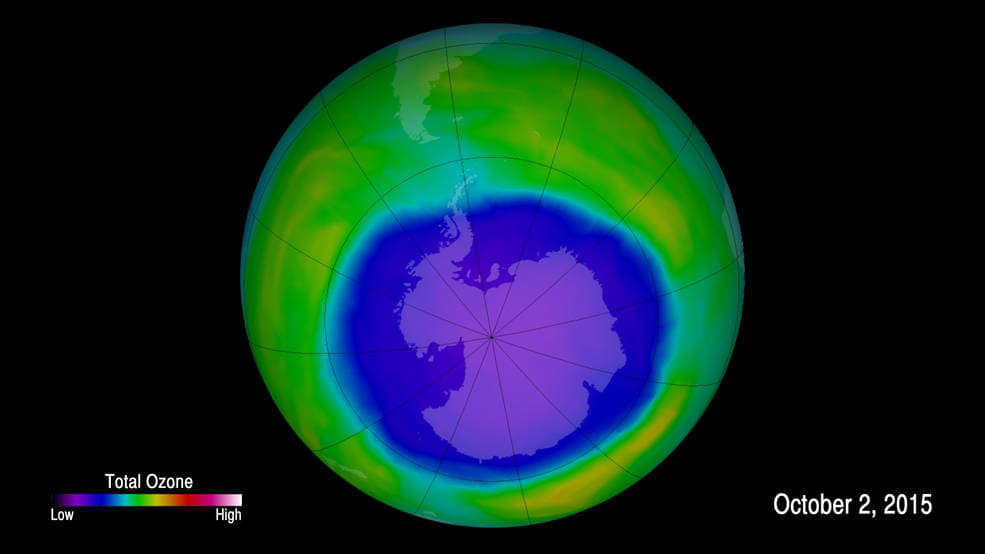

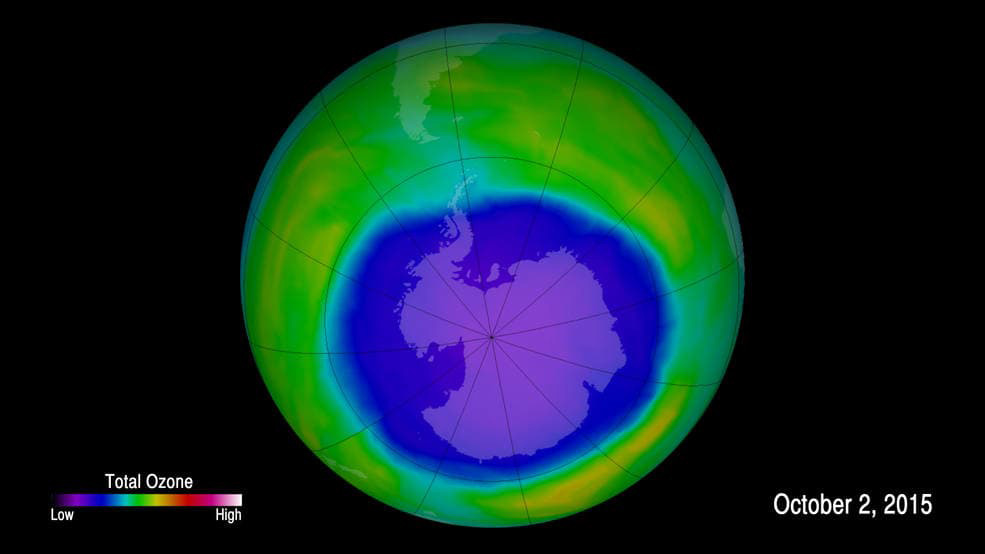

In 1987, countries of the world agreed to the Montreal Protocol, a treaty designed to phase out chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, responsible for destroying ozone in the stratosphere. The protocol has worked as intended in reducing these substances, and early healing of the ozone “hole” over Antarctica has been subsequently hailed by scientists.

But the study by Ball and his colleagues focused instead on the lower latitudes where the vast majority of humans live.

There, the scientists found a relatively small but hard-to-explain decline of ozone in the lower part of the stratosphere, the layer of the atmosphere that extends from about six miles to 31 miles above the planet’s surface, since the year 1998. Meanwhile, the upper stratosphere has been recovering.

“The precise cause of the trend is unknown but could be related to changes to the stratospheric circulation, which has a large influence on how ozone is distributed,” said Ryan Hossaini, an ozone expert at the University of Lancaster in Britain. Those, in turn, could be tied to climate change.

There’s also a possibility that a new class of chlorine-containing chemicals not limited by the Montreal Protocol, dubbed “very short-lived substances,” could be contributing to the problem. The most prominent of these substances is dichloromethane, which has a wide range of industrial uses, including as a paint stripper.

Concentrations of the substance have been increasing in the atmosphere, and because of the compound’s relatively short lifetime, it is not regulated now under the Montreal Protocol.

At the same time, though, it’s not clear that there’s enough of it in the atmosphere to be causing what scientists are now observing.

“Although so-called Very Short-Lived Substances – some of which are increasing in the atmosphere – can contribute to ozone loss, they are very unlikely to be the main driver of the reported downward ozone trend based on their current abundance,” said Hossaini.

It all amounts to a mystery, but a troubling one because ozone protects life at the surface from incoming ultraviolet radiation, and any thinning of total ozone in the stratosphere is cause for concern.

“At the moment, there’s no proof of what’s causing it but there are some reasonable hypotheses that need to be investigated,” said Ball.

“We’re raising the alarm that we need to very rapidly investigate whether it’s the short-lived compounds, whether it’s a climate change response, whether our models aren’t quite doing the right job, or whether there’s something wrong with the data,” he said.

The political implications of the new research are not immediately clear, but Ball cautioned that it certainly does not mean that the Montreal Protocol isn’t working. It just means scientists must figure out what is actually going on – the cause of the new trend “urgently need to be established,” the new study says.

In the meantime, the new research raises questions about whether additional extensions of the protocol, which is designed to be updated based on new scientific developments, may be necessary to deal with the new findings of an ozone downtrend in the lower stratosphere.

“The future evolution of ozone layer will depend on the interplay between emissions of non-Montreal Protocol controlled [ozone depleting substances], and on what happens with our climate,” said Paul Young, a climate scientist also based at Lancaster University, in an emailed comment.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.