GARDINER — Federal, state and local officials sat down at a conference table in this riverfront city more than a year ago to consider how to make Gardiner’s historic downtown more flood-resistant.

Part of that answer might lie in a report, issued Friday, that provides an assessment of how downtown buildings could be protected. But the larger question of how the federal government plans to respond to natural disasters such as floods remains uncertain.

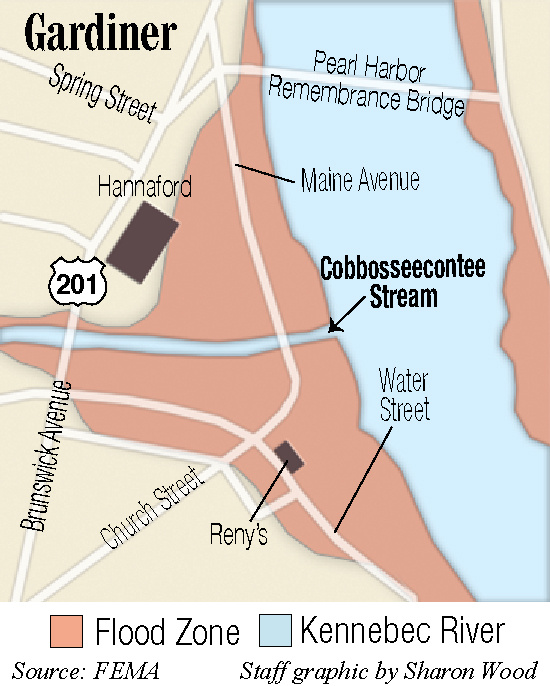

Unusual midwinter flooding along the Kennebec River this year has put the issue front and center.

The National Flood Insurance Program, which provides coverage for buildings with federally backed mortgages in identified flood plains, was already $25 billion in debt before a series of devastating hurricanes struck the nation last summer. And the program’s reauthorization, scheduled for the end of last September, has been delayed and its funding has been tied to a series of continuing authorizations voted by Congress to keep the federal government operating.

For now, some communities are forging their own path.

In late November, experts toured a historic block of buildings on Water Street in Gardiner, taking photos and making measurements. The buildings are owned by Gardiner Main Street, acquired from Camden National Bank for $1 in 2016.

The community development organization has offered the buildings as part of a pilot project to show how existing historic structures can be made more flood-resistant.

The assessment, completed by the Maine Silver Jackets program, part of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, might help determine what measures could be taken.

“The Downtown Master Plan and the Comprehensive Plan recognizes the threat of flooding exists,” said Patrick Wright, executive director of Gardiner Main Street. “There’s no specific flood mitigation plan, and there has been no coordinated, dedicated effort to deal with flood mitigation.”

HISTORY OF FLOODS

With or without mitigation plans, the Kennebec River has flooded, generally in the winter or spring, often as the result of a combination of factors – ice breakup, snow melt or rain.

A brief mid-January thaw and heavy rain shifted ice in the river, resulting in an ice jam and destructive flooding along Hallowell’s low-lying waterfront, submerging cars and flooding the lower levels of buildings closest to the shore.

In Augusta, police closed the parking lot behind Water Street. Twice, the Maine Emergency Management Agency requested ice-breaking operations by the Coast Guard.

The Coast Guard’s first attempt in late January was halted because the ice was too thick in places and the broken slabs didn’t flush down the river. The second attempt, about a month later, opened up the river south of Gardiner. While the flooding with that ice jam was relatively minor, other breakups have been much more serious.

In mid-March 1936, rain started falling as ice was breaking up on the Kennebec,. Historic photos captured in black and white the damage to bridges in the Kennebec River system, including the bridge that linked Dresden and Richmond, torqued and twisted off its supports and carried downriver.

But the largest of the Kennebec River floods – in fact, the largest natural disaster in Maine’s history – happened 31 years ago this weekend.

The massive flood of 1987 happened after heavy rain fell across the northern part of the Kennebec River’s 6,000-mile watershed. In Augusta, where the flood stage is at 13 feet, the river crested at 34 feet.

MEMA reported that 2,100 homes were flooded, 240 sustained heavy damage, and 215 were destroyed. Four hundred small businesses were affected.

Jessica Lowell can be contacted at 621-5632 or at:

jlowell@centralmaine.com

Twitter: JLowellKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.