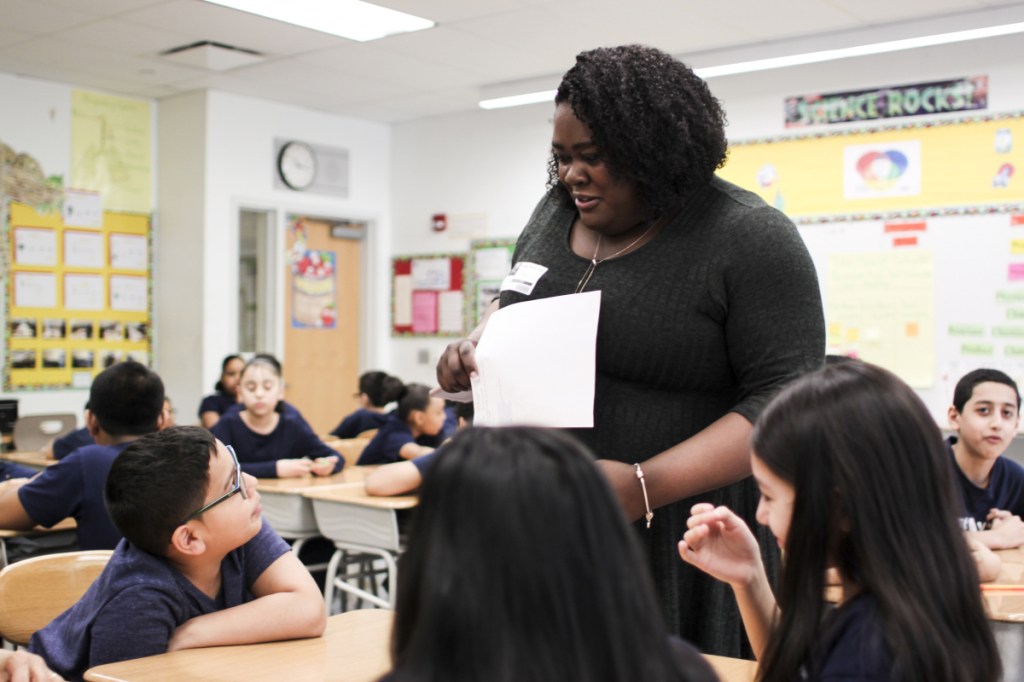

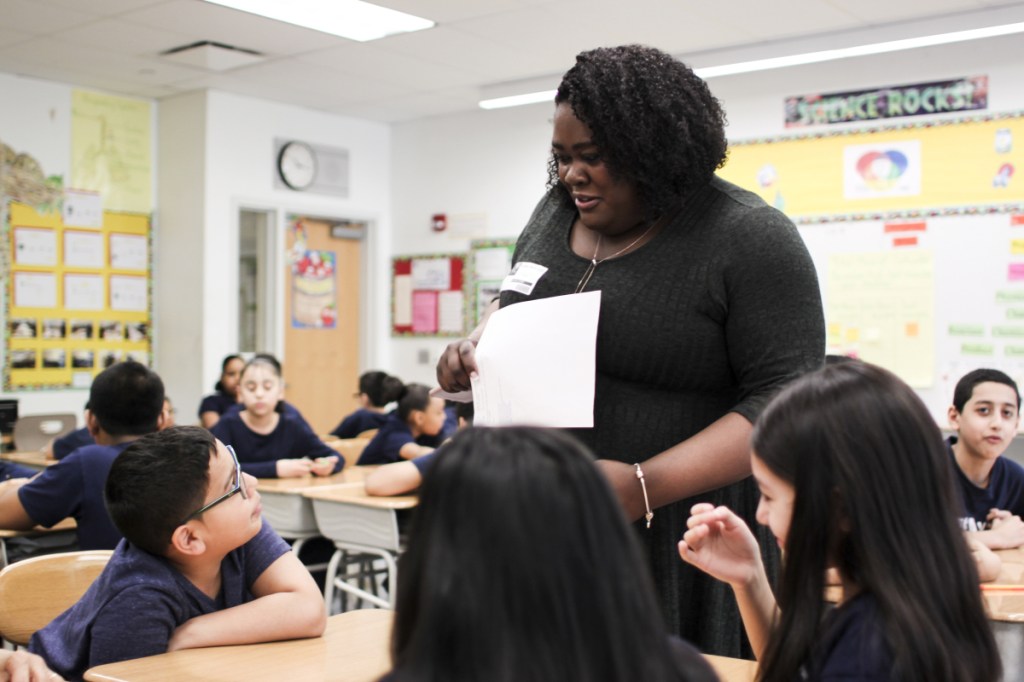

NEWARK — The fifth-graders of Yolanda Bromfield’s digital-privacy class had just finished their lesson on online-offline balance when she asked them a tough question: How would they act when they left school and re-entered a world of prying websites, addictive phones and online scams?

Susan, a 10-year-old in pink sneakers who likes YouTube and the mobile game Piano Tiles 2, quietly raised her hand. “I will make sure that I don’t tell nobody my personal stuff,” she said, “and be offline for at least two hours every night.”

Between their math and literacy classes, these elementary-school kids were studying up on one of perhaps the most important and least understood school subjects in America – how to protect their privacy, save their brains and survive the big, bad web.

Classes such as these, though surprisingly rare, are spreading across the country amid hopes of preparing kids and parents for some of the core tensions of modern childhood: what limits to set around technologies whose long-term effects are unknown – and for whom young users are a prime audience.

The course offered to Susan’s 28-student class at First Avenue School, a public neighborhood school in Newark, is part of an experimental curriculum designed by Seton Hall University Law School professors and taught by legal fellows such as Bromfield. It has been rolled out in recent months to hundreds of children in a dozen classrooms across New York and New Jersey.

The classes are free, folded into kids’ daily schedules and taught in the classrooms where the fifth- and sixth-graders typically learn about the scientific method and the food chain. Gaia Bernstein, director of Seton Hall Law’s Institute for Privacy Protection, which designed the program, said each class includes about a half-dozen lessons taught to the kids over several weeks, as well as a separate set of lectures for parents concerned about how “their children are disappearing into their screens.”

Professors designed the program – funded by a $1.7 million grant awarded by a federal judge as part of a class-action consumer-protection settlement over junk faxes – to teach students about privacy, reputation, online advertising and overuse at the age when their research found that many American kids get their first cellphone, about 10 years old, though some in their classes were given phones years earlier.

The Seton Hall instructors speak of the classes in the same ways others might talk about sex education – hugely important, underappreciated and, well, a bit awkward to teach.

But they said they had no interest in teaching kids digital abstinence or instructing parents how to be the computer police. The internet, they conceded, is a fact of life – and the kids always find ways around their parents’ barriers, anyway.

In designing the classes, Bernstein said she was surprised at how little attention most schools paid to the digital worlds its students were immersed in every day – and, as a parent, she often wished she had done things differently with her 15-year-old son.

She could find few other classes that included both the kids and parents in broader conversations about tech dependence and digital tracking. Other programs, she said, seemed unrealistic or out of date, aimed at choosing good passwords or avoiding bad chat rooms but silent on the daily questions of attention and privacy.

“Everybody seems to focus on things that are unlikely – a stranger online taking your child away,” Bernstein said, adding, “There are things that happen every day that parents aren’t taught about – children posting things on Instagram or a group text that could have an effect on their social lives, their college admissions, their futures.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.