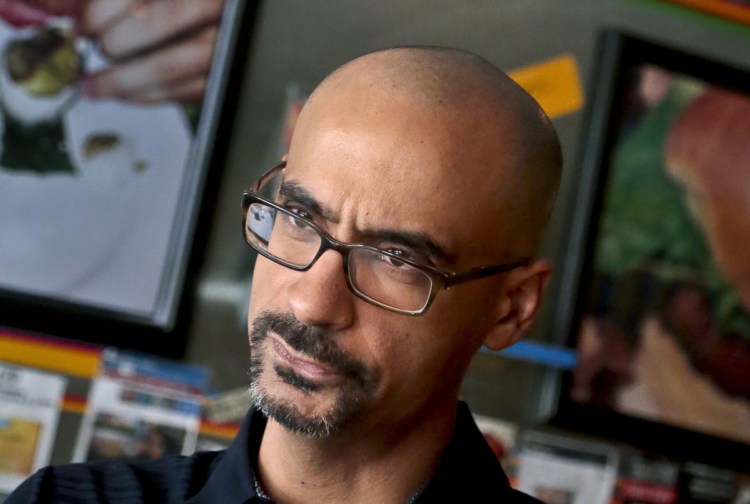

Long before an emotional public disclosure of his childhood rape, or the allegations of his own sexual misconduct that followed, author Junot Diaz was a pioneering and polarizing figure.

He emerged as one of the few prominent Latino voices in English literature, with a reputation earned through story lines that featured blurred sexual consent, victims who wanted to be victims and characters caught in a cycle of unhealthy relationships. The plots edge eerily close to some accounts his accusers have shared.

The women, empowered in part by the (hash)MeToo movement, broadened his notoriety with their allegations of abusive behavior. They told of forced kisses and inappropriate verbal attacks, leaving the literary and academic community grappling with the fall of one of the most acclaimed minority authors in the 21st century.

“It’s hard to really overestimate how prominent his voice is,” said Melissa Gonzalez, assistant professor at Davidson College in North Carolina. “He’s one of the few Latinos who has really not only been canonized but also established his voice as very important.”

Diaz did not respond to a request for comment from the Associated Press. But he told The New York Times he takes responsibility for his past.

“I am listening to and learning from women’s stories in this essential and overdue cultural movement,” he said. “We must continue to teach all men about consent and boundaries.”

A 49-year-old Dominican-American writer known for mixing Spanish and English in his prose, Diaz has broken down barriers in the literary mainstream. From a 6-year-old immigrant new to New Jersey to an award-winning author and professor, he defied the odds to become an American success story.

He landed on The New Yorker magazine’s “20 Under 40” list in 1999. By then, he’d already published his first short story collection, “Drown.” In 2008, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his first novel.

In 2012, Diaz was awarded a MacArthur genius grant, and his second short story collection, “This Is How You Lose Her,” earned a spot on The New York Times’ “100 Notable Books.”

Diaz became a go-to name for teachers, who directed students to his work when trying to show how diverse American literature can be, said Joseph George, a lecturer at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro.

“Personally, I was intrigued by the way he exposed the male ego,” George said. “It seems foolish now to say it, but I read it as a confession and a deconstruction that we could look at why men think this way.”

George often assigned Diaz’s “How to Date A Brown Girl (black girl, white girl, or halfie)” in his class. Some students recoiled at the title alone. They told him they found its narrator “disgusting,” but he pushed them to delve further and try to see how the text agreed with them.

George, a white man who said he has never suffered sexual misconduct, now does not feel equipped to incorporate Diaz’s work in his courses.

“I’m not the person to teach it, at least not now,” George said. “It requires a different level of expertise and sensitivity.”

He’s not alone. Greg Barnhisel, an English professor at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, has opted not to use Diaz’s books for a gateway English class next academic year. He does not want to spend the time unpacking Diaz’s personal life instead of focusing on literature.

The accusations against Diaz began with a panel at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on May 4, when author Zinzi Clemmons confronted him about how he had allegedly mistreated her when she was in graduate school. Hours later, after Clemmons tweeted that Diaz cornered and forcibly kissed her six years ago, other women took to social media to share their stories of verbal abuse and perceived misogyny by him.

Before the allegations surfaced, Diaz had published his own story of childhood abuse, revealing in The New Yorker last month that he was repeatedly raped when he was 8 years old.

“It is time for the burden of his bad behavior to be laid squarely at his feet, and for him to deal with the consequences of his actions,” Clemmons wrote in a statement to the AP. “Not in a self-serving personal essay, but by losing some of what he has accumulated while conducting himself in this manner.”

Reaction has been swift. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Diaz teaches, is investigating, and the Pulitzer Prize Board is conducting an independent review.

Though readers have expressed their disappointment over the allegations, some see the scandal as an opportunity for other Latino writers to get noticed.

“His literary presence has sucked a lot of the air out of the room,” said Gonzalez, the Davidson professor. “A lot of the anger in this moment is about that fact.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.