The conversion of Turner V. Stokes began with teenage skinny-dipping and concluded, some 30 years later, at a nudist retreat in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains. He had gone mainly out of curiosity, taking his wife after their two children had grown up and left home. What he found, he later said, was “a feeling of freedom” and a growing sense that the nudist movement could “benefit humankind.”

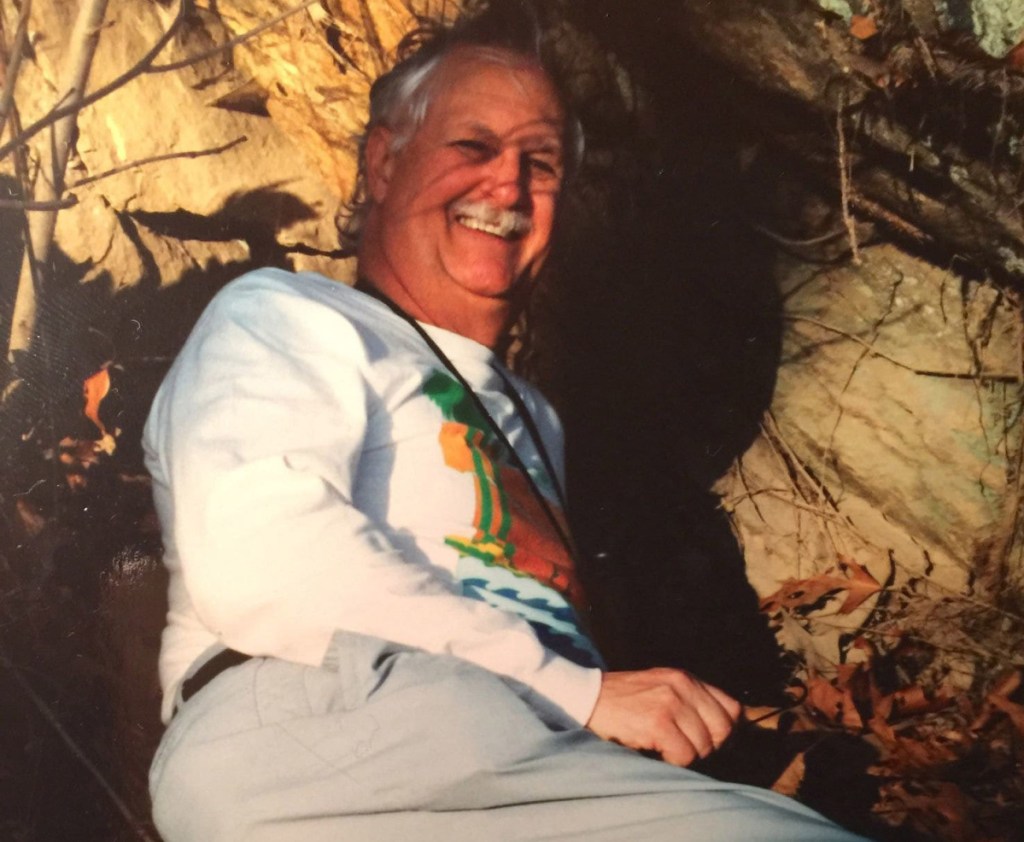

Stokes, an engineer who usually wore a suit in the office but nothing at the beach, went on to become one of the most prominent advocates of nudist spaces, calling for protections for those who wished to bare all in the face of hostility from government officials, religious leaders and other critics who linked nudity to moral perversity.

As president of the country’s largest nudist organization, and then as chief of its government affairs committee and political fundraising branch – Nudepac – he became “an omnipresent figure in Washington,” said Bev Price, current president of the American Association for Nude Recreation.

In meetings with lawmakers, as well as in interviews with talk-show host Phil Donahue and news organizations including The Washington Post, Stokes “advanced the understanding of nudism,” Price said in a phone interview. “People knew he was a nudist, by golly, and he never pulled any punches.”

Stokes, who viewed nudism as a civil rights issue and spearheaded political and legal campaigns on behalf of the unclothed, died June 23 at his son’s home in Nanjemoy, Maryland. He was 90.

The cause was prostate cancer, said his brother W. Royal Stokes, a former Washington Post jazz critic.

A bespectacled Navy veteran with a thick white mustache, Stokes did not present himself as a radical so much as a rebel. He abided by the rules of “textile” beaches (the nudist term for a clothed beach) and never practiced “naturism,” as he called it, in the company of those who hewed to more traditional social norms.

Instead, he became a circumspect evangelist for a lifestyle that, to his mind, promoted the unequivocal acceptance of the human body.

“It’s so hard to explain what the appeal is, because you don’t understand it until you participate,” he told The Post in 1984. “If you’ve ever gone into the ocean without a swimsuit, you’d never wear one again. The thought of a swimsuit is disgusting. Who wants a wet, slimy swimsuit?”

Stokes was president of the AANR, then known as the American Sunbathing Association, from 1986 to 1988. While he called for protections for nude beaches and gatherings across the country, he was best known for his work on Assateague Island, the 37-mile barrier island that straddles the Maryland-Virginia state line.

In the early 1980s he helped create a nude beach on the island, and through the National Capital Naturists – a group he organized with writer Lee Baxandall – he oversaw efforts to preserve the sand dunes and clean up litter along the shore. After an article in Playboy magazine drew the attention of local officials, however, Virginia’s Accomack County passed an anti-nudity ordinance that effectively shut down the gathering site. If caught, nude sunbathers faced a $1,000 fine and up to one year in jail.

Stokes led a more than $50,000 effort to fight the ordinance in court, urging fellow nudists to oppose the “self-righteous, self-styled moralists . . . who claimed that we are to be likened to pornographers, child molesters, rattlesnakes and agents of the devil.” The legal campaign was financed in part by the sale of T-shirts reading “Bare Assateague.”

After the Supreme Court upheld a ban on public nudity in 1991, however, Stokes and other trunk-free bathers abandoned their Virginia legal efforts for ostensibly freer swimming grounds across the Maryland border, in a section of the island controlled by the National Park Service.

Rangers at the Assateague Island National Seashore began enforcing a Maryland state ban on public nudity in 1996, although Stokes said that he and fellow nudists ultimately achieved a form of detente with park authorities. Nudism, he suggested, was little different from horseback riding, windsurfing or any other form of recreation.

“We encourage people to be responsible, not to flaunt nudity around those who might be offended,” he told the Baltimore Sun in 2001. “Frankly, I don’t think there are a lot of rangers interested in aggressive enforcement as long as people behave responsibly.”

Turner van Cortlandt Stokes was born in Washington on Dec. 17, 1927, and spent his early years in the city’s Adams Morgan neighborhood, in a home that later became the after-hours jazz club Villa Bea.

His mother was a homemaker, and he traced his rebellious streak to his father, a World War I aviator who fought prohibition in court and later worked as an equipment purchaser at Western Electric.

Stokes was about 10 when the family moved to Gibson Island, Maryland, where he occasionally swam naked. He later recalled buying his first nudist magazine as a teenager, and – on a lark – running through the woods nude with a cousin.

Returning to the District of Columbia for school, he graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in 1945 and enlisted in the Navy, days before the Japanese surrender ended World War II. He studied electronics in the Navy and then at several Washington-area schools, graduating from George Washington University in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in engineering.

For decades, Stokes focused almost entirely on his work with military contractors such as Melpar, testing electronics equipment until his retirement in 1992. He began his nudist activism only in his 50s and said his work never flustered employers or prevented him from receiving a security clearance.

His marriage to Sara Wood ended in divorce, and he married LaVerne Utterback Kinehan in the late 1960s. She died in 2001.

Survivors include two children from his first marriage, Sue Stokes Bridgett Becker of Annapolis and Robert Bruce Stokes of Nanjemoy; two stepchildren from his second marriage, Shannon Donoway of Port Charlotte, Florida, and Tim Kinehan of Halifax, Virginia; two brothers; and three granddaughters.

Stokes lived on a rural property in Leesburg, Virginia, before moving to his son’s home in recent years. The perks of a secluded house, he told The Post, included walking naked whenever he wished – weather permitting, of course.

“Clothes, basically, in surroundings like we’re in, are to protect you from the elements,” he said. “If it’s cold, you wear clothes, if it’s hot, you don’t. And of course women especially like to be able to get a good tan without all these strap marks and all those complications. Getting a suntan is a minor consideration as far as I’m concerned.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.