During her workweek at the Maine Humanities Council, Freeport writer Diane Magras raises funds for literary and library programming across the state. On her own time, she chronicles in a new novel the adventures of a scrappy, medieval girl hundreds of years and thousands of miles away.

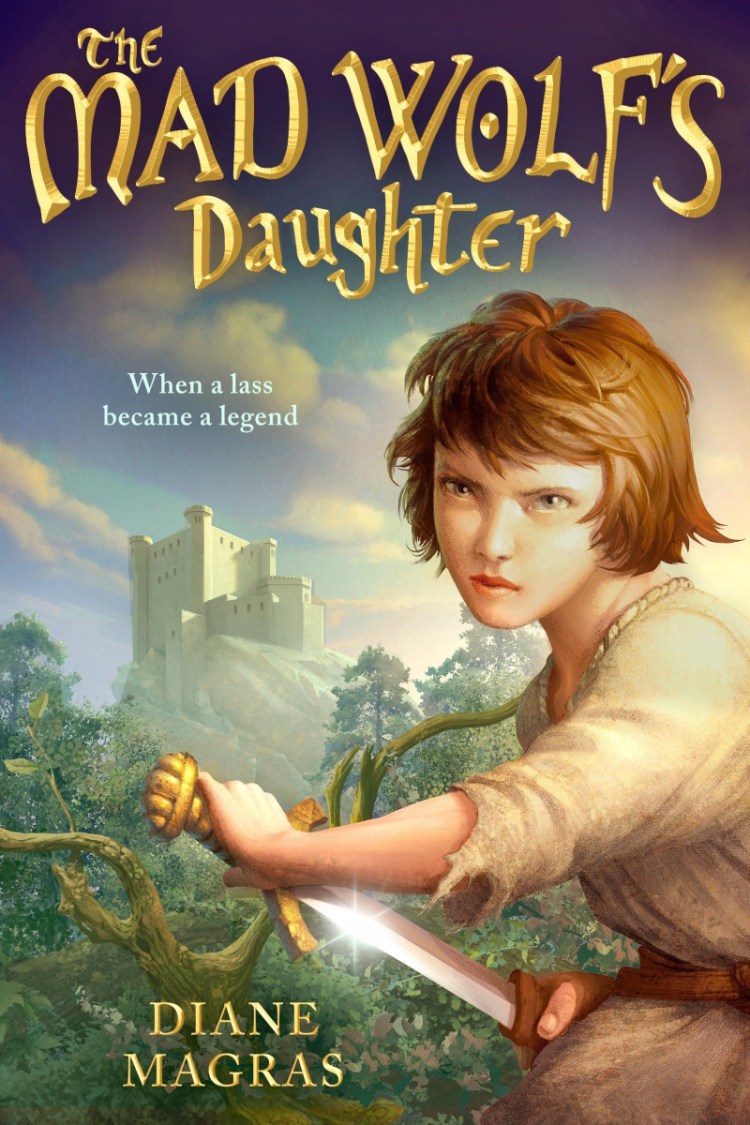

Magras’ debut novel, “The Mad Wolf’s Daughter,” published in March by Kathy Dawson Books, is written for middle-grade readers. The narrative follows 13th-century pre-teen Drest on her quest to save her father and brothers after they are captured on the Scottish headlands by invading knights. Accompanied by a wounded knight and a knowledgeable local boy, Drest must make her way to the castle where her family is scheduled to be executed in five days. It’s an adventure full of danger, startling revelations and brave endeavors.

“The Mad Wolf’s Daughter” explores how legends grow, as Drest discovers hidden talents in herself and sees her family’s story reinterpreted by strangers.

Diane Magras

In the opening chapters, Magras emphasizes the closeness Drest feels for her father and brothers as they exchange stories and advice. Magras writes, “Here she had sat rapt as her brothers had spoken of blows and broken shields in battle, of the swiftness that had saved their lives. She’d grabbed her own share of ale and meat and gone to sit with her father, who’d tuck her under his rough, warm arm as he told his tales of castle sieges in the days when he’d fought among knights of another war-band.”

In a telephone interview, Magras, 44, said she is inspired by an “idyllic” childhood spent on Mount Desert Island. She lived five minutes from the beach, close to Acadia National Park. “I grew up climbing all of the mountains and scrambling over the boulders.”

That’s why she created the Headlands. “Drest’s journey mirrors many of the landscapes that I grew up with. It’s Scotland as seen through Mt. Desert eyes.”

Always an avid reader, Magras wrote her first “novel” in seventh grade, encouraged by her English teacher, Lisa Plourde, who told her about a 15-year-old author.

Magras said, “So I thought, well, I won’t write just stories. I’ll write an actual novel. It was a fantasy with a sword, but the girl wasn’t carrying the sword in that one, unfortunately.”

She said that the book that had the biggest impact on her as a young reader was “The Dark Is Rising,” by Susan Cooper, which mixes elements of European myth.

“That was the book that showed me how to tell a really powerful fantasy, how to create a world, how to create drama.”

A graduate of the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Magras has written – but not published – novels for adults. “I have two novels that I tried very seriously to get published,” she said. “But I’m glad I didn’t (succeed), because they’re not worthy.”

It wasn’t until she started sharing books with her now 11-year-old son, that Magras saw the potential of middle-grade fiction.

“The book that really made me want to start to write middle-grade was ‘The Luck Uglies’ by Paul Durham,” she said. “The adventure, the optimism, the imagination and the depth – I hadn’t realized that middle-grade fiction could handle so many big themes so beautifully.”

Middle-graders need special attention, noted Magras, as they build identities separate from other members of their families.

“It’s a really tough time,” Magras said. “And I want my novels to be there for kids who are struggling and need a fun, imaginative book with good themes that they can explore as much as they want to.”

Scotland is a fair reach from Maine, but Magras has traveled there a few times: once at age 13 and twice to research “The Mad Wolf’s Daughter.” Of Scottish heritage by way of Ulster, Ireland, Magras said it “was so incredibly inspirational to go up into these monuments, these fortresses, and examine the details. Historic Environment Scotland is one of the major heritage organizations there, and they do an incredible job of keeping up the properties.”

Although “The Mad Wolf’s Daughter” is marketed as a fantasy novel, Magras prefers to call it a “historical adventure,” as there’s no magic at play in it.

“Magic would have given me so many easy outs,” Magras said. “I realized that the world Drest lived in was difficult enough without that.”

“I wanted to write something that had the heart-pounding excitement and the cliffhanger chapter endings that you find in great fantasy novels. But all with historical (accuracy).”

Magras is married to author and book critic Michael Magras, whom she met at The Stonecoast Writers’ Conference in 2002.

“I read his work and give him comments. He reads mine,” she said. “It’s fantastic being married to a writer who understands what I’m trying to do.”

In her capacity as Director of Development, Magras is the editor, writer and chief fundraiser for the Maine Humanities Council, on staff since 2004. She was working for the Vermont Symphony Orchestra in development when she jumped at the MHC job posting. “How many organizations are out there that deal with literature and books and things of the mind?”

The state’s affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Maine Humanities Council, offers programs and grants for all Mainers.

Magras said, “Our library program always impresses me because it gets into the smallest communities and brings something free that everyone can participate in. That really bridges differences and gives people who may not have a lot of cultural opportunities a place where they are welcome.”

Magras also mentioned “Literature & Medicine,” a reading and discussion program that gives health care professionals the opportunity to reflect on their professional roles and relationships through reading plays, short stories, poetry, fiction and personal narratives.

According to the MHC website, “Literature & Medicine” is the only national program that engages a cross-section of experienced health care professionals with the humanities.” It touts the program’s success at improving provider communication skills, cultural awareness and empathy for patients, and says that another innovative program, the Veterans Book Group, was an outgrown of Literature & Medicine.

Almost one-third of the council’s funding is provided by a base grant from the NEH. Funding for the arts sometimes becomes a political issue, but for the moment, no cuts seem imminent.

“(NEH funding) hasn’t been reduced, thank goodness, but it has been threatened,” Magras said. “We’ve been worried about that. That would directly affect the amount of programming we can offer. We’ve been lucky.”

As for the sequel to “The Mad Wolf’s Daughter,” Magras is already working on it. The story picks up only hours after the end of the first volume. The author declined to provide many details, but readers can be assured that plenty of historical adventure lies ahead.

Berkeley writer Michael Berry is a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, native who has contributed to Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, New Hampshire Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and many other publications. He can be contacted at:

mikeberry@mindspring.com

Twitter: mlberry

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.