The question was about playbooks. Gardiner coach Joe White just chuckled, then shook his head.

“It can turn into a monster real quick,” White said. “You start out week one of preseason, and you put maybe 10 or 15 plays in, and by the first game you’ve got a script of 80. You’ve got to dial it back a bit.”

Playbooks are the nervous system of a football team. They include everything, from the plays to run, to the schemes to use, to the assignments to follow. And no two playbooks are the same. Some have detailed route combinations for receivers, some consist almost entirely of blocking schemes. Some are expansive, while others stick to a core group of plays. Some aren’t even literal playbooks, but instead are either plays and concepts accessed digitally, while some teams stick with the old-fashioned notebooks, binders and hard copies.

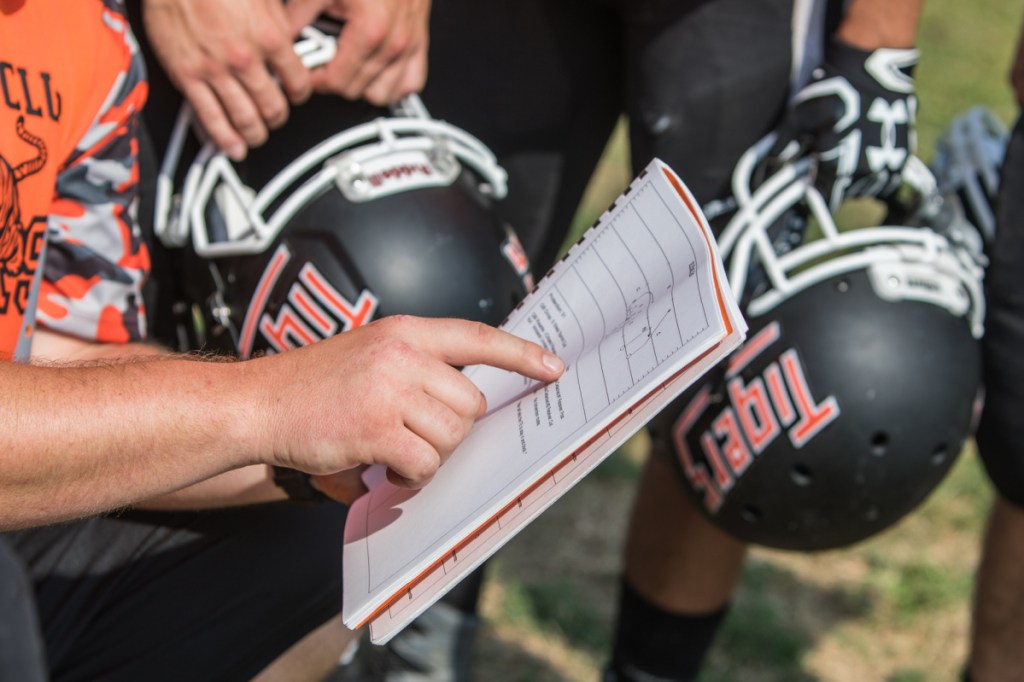

Photo by Jennifer Bechard Gardiner football assistant coach Michael Simpson points out plays from a playbook during practice Wednesday afternoon at Gardiner Area High School

In all cases, however, there’s a consistent rule: Whatever you’re running, keep it simple.

“You can get carried away and try to get cute and creative,” White said. “It’s like the old saying, 1,000 knives, none sharp. The same thing applies to your playbook.”

“It really comes down to what we think they can handle mentally, because you could have a limitless playbook,” Cony coach B.L. Lippert said. “You don’t want to overburden them with 400 plays, but you also want to be diverse enough where you can take advantage of a defensive weakness you’ve seen on film.

“It’s a tough balance. When kids are confused, they slow down. They aren’t as physical, they aren’t as fast.”

The structure of these playbooks has changed over time. The notion of the thick, physical book is largely outdated, with digital options opening up new ways to convey the information. Some coaches, like Messalonskee’s Brad Bishop, still use literal books, with hand-stenciled routes and formations.

“It really hasn’t changed much, I do most of mine by hand,” he said. “They get a playbook at the beginning of the year, then they get one every week during the season for the opponent. They get quite a bit of information.”

Others, like White, have embraced the digital possibilities for understanding the playbook’s intricacies. The Tigers use Hudl, a website that allows players and teams to post highlights and videos, and White can both share the plays there and provide breakdowns of how they run.

“It’s all digital, they can look at it on their phone,” White said. “(You) can pick out whatever game from last season or two years ago that you want to watch, bang. Playbook right there, you can just (read) right through it.”

Whatever the format, the objective is the same. Boiling it down is a goal of all coaches at the high school level, where players can’t be expected to spend hours and hours memorizing long play codes. The key is to funnel the playbook into a handful of schemes and concepts, which can then be tweaked to deepen what a team can throw at an opponent.

“If we’re telling players, ‘Hey, memorize 50 different pages,’ it might be a little difficult,” Madison coach Scott Franzose said. “If you look at our playbook, it looks like we have a lot of different code words for a lot of different run plays. … It might look like we have 20 different run plays, but five of them are tagged to the same concept.”

The key to knowing the concept is in the language of the play. One or two words reveal everything to the players, from the direction of the play to the formation to the individual assignments. At Maranacook, coach Walter Polky uses college teams and mascots to facilitate the plays in his 150-page playbook. The “P” and “R” in “Panther” could mean a power run to the right. The “O” in “Oregon” could indicate an option. When he adds a formation from the sideline, the Black Bears have their play.

“When we call a play, it’s one word,” Polky said. “It’s not like the NFL, where it’s X, Y, H Cross, things like that. … One main reason you can’t go overly complicated with the verbiage is you don’t have time to teach all of it.”

Even with passing routes, the principle holds. Players learn early on the routes involved with a rub concept or a smash concept, so hearing those words in the name of the play reveal, based on where they line up, what they’re supposed to do.

“We try to keep the terminology as tight as we can, because you don’t want to have those 15-word play calls because we don’t have headsets,” Lippert said. “If (my quarterback) forgets it on the way back in, we’re going to get a delay of game. That’s why they can get away with lengthier play calls in the NFL.”

Simplifying the playbook also comes down to putting the emphasis on practice and repetition, rather than memorization. Asked if the notion of players needing to spend hours poring over their playbooks was an outdated notion, Lippert didn’t hesitate.

“Yes, 100 percent,” he said. “When they’re in front of you, that’s your best opportunity to get them to learn.”

Instead, players learn the calls down cold by going over them relentlessly in practice. Lippert doesn’t even give his team a playbook, instead introducing plays during practice and having his players learn them on the field.

Photo by Jennifer Bechard Gardiner football assistant coach Michael Simpson uses an iPad to point out plays during practice Wednesday afternoon at Gardiner Area High School. From left, are players Sean Michaud, Cameron Michaud, Keatin Gaither, Nate Malinowski, and Terren Medeiros.

“You get the hang of it after a while because we just run through the plays every day in practice. It gets stuck in your head, honestly,” Cony receiver and tight end Matt Wozniak said. “I never forget them. We go over it like 300 times, it’s crazy.”

Even coaches with a playbook use it more as a reference point. The offense and defense are installed on the field, not at home.

“Out here, it’s constant repetition. We run a certain set of plays on Monday, a certain set on Tuesday, then we go back to Monday’s plays on Wednesday and Tuesday’s plays on Thursday,” Bishop said. “We’re seeing the same plays twice a week. Same thing on defense.”

And with only so many hours with which to work, there are only so many plays to go over. And as teams find out, the simple approach is often best.

“You can have an extensive playbook, but if you’re not able to execute all those plays, you probably should hit the reset button,” White said. “Do four or five that you can rep over and over to perfection.”

Drew Bonifant — 621-5638

dbonifant@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @dbonifantMTM

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.