Yet, the harsh fact is that in many places in this country, men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes. Every device of which human ingenuity is capable has been used to deny this right.

– Lyndon Johnson, Voting Rights Act Address, 1965

With the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, many Americans (except African-Americans and Latinos) believed that the voting rights fight was over – taken care of, time to move on. Democracy won. Next.

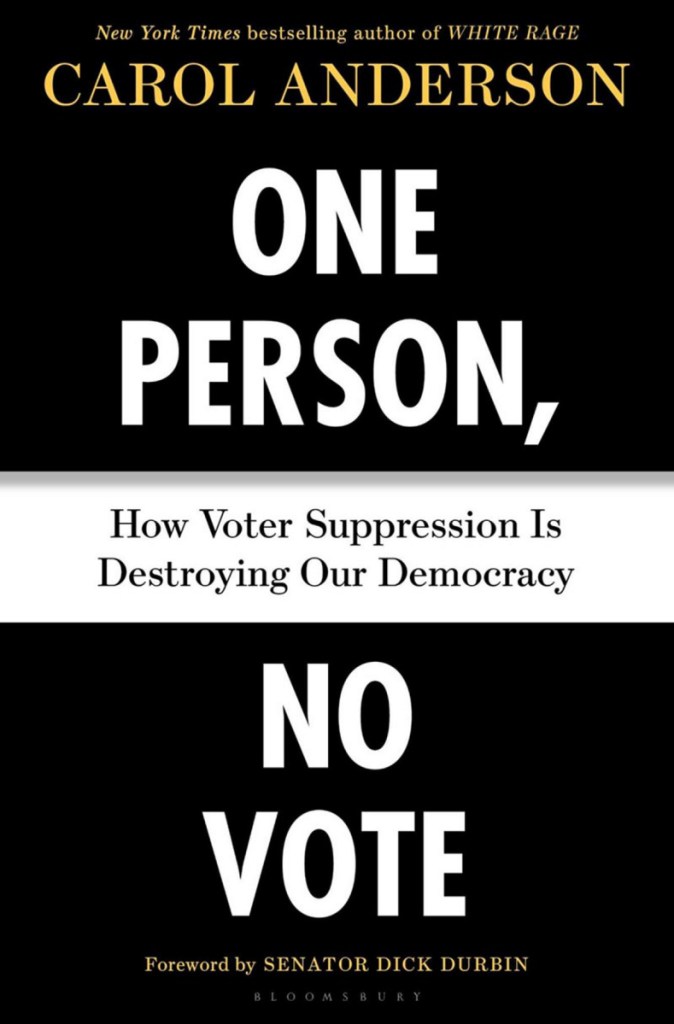

But as Carol Anderson demonstrates in her powerful new book, “One Person, No Vote,” the right to vote – a central tenet of our democracy – is under threat. Chief Justice John Roberts has said voting is “preservative of all other rights.” If that is so, then according to Anderson, all our other rights are in serious jeopardy. Her book is a disturbing drill down into how the right to vote is being slowly destroyed with too few of us noticing.

“One Person, No Vote” is an important sequel to Anderson’s “White Rage,” which examined the nefarious ways white America sought to oppress, repress and marginalize African- Americans after the Civil War. The key element of that oppression was an ongoing – and successful – effort to deny blacks the right to vote. Some tactics were less than subtle: poll taxes, literacy tests, limited hours for voting, allowing only whites to vote in primary elections. Other strategies were violent and cruel: Blacks were subjected to rampant voter intimidation and lynchings. Many were incarcerated on made-up charges and then as felons denied the right to vote. The deterrents worked. In 1867, just after the Civil War, more than 65 percent of newly enfranchised blacks registered to vote in Mississippi; by 1955, that figure had plummeted to 4.3 percent. The same dismal story was witnessed all across the South.

But 100 years after the Civil War, the 1965 Voting Rights Act gave blacks unfettered access to the ballot box. And with its passage, it seemed that the moral universe was, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr., bending toward justice – and democracy. By 2008, in North Carolina, a higher percentage of blacks voted than whites.

But when Anderson examined voting patterns in the 2016 presidential election, she discovered that some black voters had disappeared, a circumstance that she calls “the campaign’s most misunderstood story.” In 2016, the number of black voters nationwide dropped from a 66 percent turnout to under 60 percent. The decline was even more precipitous in places like Milwaukee, where it slumped from 78 percent of African-Americans voting in 2012 to less than 50 percent in 2016. And thanks to those lower turnouts, Donald Trump carried Wisconsin by a slim margin of fewer than 23,000 votes.

Anderson argues that this decline in black voters in 2016 was not a one-time anomaly but rather was evidence of a systemic hijacking of our democracy. The genesis of the hijacking began after Barack Obama’s 2008 election. Republicans then faced a quandary: How should they deal with the rising demographic tide of minority voters? In 1992, nonwhites represented just 13 percent of the voting population – by 2012, they were 28 percent. Republicans had a choice: They could change their policies to appeal to new voters or find a way to suppress their votes.

As Anderson makes clear, they chose the latter.

Republicans took to heart the words of Paul Weyrich, the conservative founder of the Heritage Foundation. In a 1980 speech, he opined: “I don’t want everybody to vote. … As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.”

Anderson catalogs how Republicans, beginning after 2008, put Weyrich’s manifesto into action. Their tactics included purging voters, gerrymandering, instituting voter-ID laws, closing polling places and preventing felons from voting (1.7 million felons aren’t allowed to vote in Florida – representing about a fifth of possible black voters). As Anderson writes, “Voter suppression had now gone nationwide as it became a Republican-fueled chimera that by 2017 gripped 33 states and cast a pall over more than half the American voting-age population.”

In 2010, Republicans managed, with generous funding from the Koch brothers among others, to take over numerous state legislatures in the midterm elections. Soon, state after state, most of them Republican-controlled, passed new voter laws, often requiring stricter types of identification. These voter IDs included driver’s licenses that white voters often had or could easily get. Not surprisingly, these IDs were much less commonly held by minority voters. For instance, when Texas enacted a voter-ID law in 2013, 600,000 African-Americans and Latinos did not have the proper ID to vote. Sherrilyn Ifill of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund sees these voter-ID laws as “old poison in a new bottle.”

Republicans claimed that voter-ID laws were the perfect prescription for an election system that was riddled with voter fraud. Yet Anderson amply demonstrates that a slew of academic studies prove that voter fraud, or illegal voting, is very rare. In fact the North Carolina Board of Elections found that out of the millions of votes cast in the state in 2016, there was only one case of voter fraud that a voter-ID system would have prevented. Yet half of Americans believe that voter fraud is common.

And it is not only politicians who have rallied to the cause of finding new ways to make voting more difficult. In 2013, the Supreme Court, by a 5-to-4 vote, overturned a key clause of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The pre-clearance clause required many Southern states to clear any changes in state election laws with the Justice Department before implementing them. After the court’s ruling, a number of Southern states, including North Carolina and Texas, quickly put voter restriction laws into effect. North Carolina’s law required a stricter level of voter ID, cut back on early-voting days and did away with same-day voter registration. The illegitimacy of these laws was demonstrated in the summer of 2016 when federal courts struck down or amended many of them. Of the North Carolina law, the federal court wrote that it targeted “African-Americans with almost surgical precision.”

Despite these federal court rulings, politicians proved adept at coming up with innovative laws to suppress the minority vote.

After Obama carried Indiana in 2008, the Republican legislature of this traditionally red state, along with its then-governor, Mike Pence, passed a law that said counties with more than 325,000 registered voters could have only one early-voting site unless the county election board ruled otherwise. In Indiana, there are only three counties with more than 325,000 registered voters; all three have large numbers of black voters. And data shows that blacks vote early in much higher percentages than white voters do. As a result of this new law, early voting in Marion County, which comprises Indianapolis and, as Anderson puts it, “the lion’s share of African-Americans in the state,” fell 26 percent. In 2012, Indiana went for Romney and in 2016 for Trump.

As we look toward this fall’s elections, Anderson gives us the lowdown on the voter suppression tactics of two Republican candidates running for governor: Brian Kemp in Georgia and Kris Kobach in Kansas. Both men are currently secretaries of state, the office that oversees state elections. Both preached the dogma of voter fraud and the need for what they call “election integrity” – code words, according to Anderson, for voter suppression.

Kobach was also vice chairman of Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, which was formed after Trump claimed that millions of noncitizens voted illegally in 2016. But the commission crumbled after eight months and found no proof of voter fraud. Nonetheless, Anderson sees Kobach as an accomplished practitioner of the dark art of voter suppression. He passed a Kansas law requiring proof of citizenship to register to vote. The American Civil Liberties Union sued. When a federal court agreed with the ACLU and banned the practice, Kobach quickly adjusted and made proof of citizenship a requirement for registering to vote in state (not federal) elections.

For his part, Kemp fought to turn back the rising demographic tide in Georgia. Anderson notes that while the state’s population has grown, unbelievably, the number of registered voters has dropped since 2012 (Kemp was elected in 2010). This is due in no small part to Kemp, a “voter-suppression warrior,” in Anderson’s words, who led a purge of more than 1 million voters from the rolls between 2012 and 2016.

If the trend in voter suppression looks bleak, Anderson finds a ray of hope in Alabama’s 2017 special Senate election. In that vote, African-Americans overcame myriad voter suppression obstacles and turned out in high numbers to elect the Democrat, Doug Jones, and defeat the Republican candidate, Roy Moore. Moore had infamously said, among other things, that removing all the constitutional amendments passed after the 10th “would eliminate many problems.” Those amendments abolished slavery, guaranteed the right to vote without racial discrimination and gave women the vote.

While Anderson notes some progress in battling voter suppression, she remains clear-sighted about the continuing dangers. She decries how voter suppression skews the electorate and the resulting consequences to our democracy. “Voter suppression has made the U.S. House of Representatives wholly unrepresentative,” she writes. “It has placed in the presidency a man who is anything but presidential. It has already reshaped the U.S. Supreme Court … and as a slew of Trump’s unqualified nominees to the federal bench get greenlighted by a compromised Senate, it threatens to undermine the judiciary for decades to come.” Her conclusion: “In short, we’re in trouble.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.