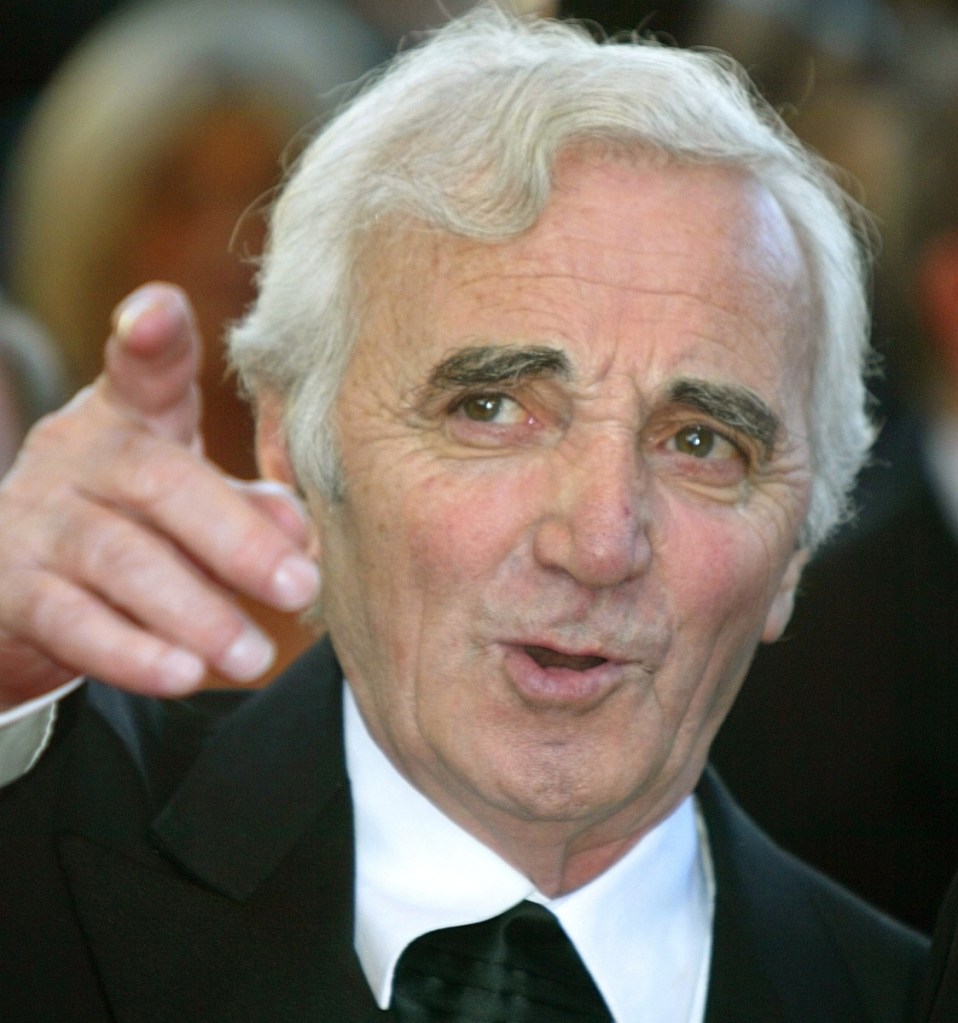

Charles Aznavour, the French singer and composer who became an international sensation for ballads that surveyed territory often unexplored in popular music – embittered marriages, squandered lives, and, daringly in the early 1970s, homosexuality – has died. He was 94.

The French Culture Ministry confirmed his death. Additional details were not immediately available.

One of the music world’s most captivating and prodigious stars – admired by entertainers as varied as Frank Sinatra and Bob Dylan – Mr. Aznavour wrote or cowrote about 1,000 songs and sold more than 100 million albums. He recorded or performed in French, Spanish, English, Italian and German, bewitching audiences with an alchemy that Time magazine once described as the commingling of “fire and sorrow.”

Diminutive and wiry, with mournful, beetle-browed eyes and a raspy tenor voice, Mr. Aznavour lacked the rakish sex appeal and ebullience of chanteurs such as Maurice Chevalier and Yves Montand. But he surged to fame in the 1960s, selling records on pace with Elvis Presley and the Beatles and drawing superlatives from critics for a charisma that was more implosive than explosive and for songs that illuminated the darker corners of the human heart.

Mr. Aznavour was one of the last surviving links to the mid-20th-century golden age of the “chanson française,” a song tradition blending streetwise, poetic lyrics and accessible melodies. Some of its most revered interpreters included Édith Piaf, a mentor to Mr. Aznavour.

Calling his songs “sketches of life,” he made an art form of ballads about bruised souls, crafting story lines shaded with irony and bitterness. Many of the ballads – ruminations on grief, remorse, longing, treachery and bliss – concerned the emotional chasms that open between people.

In “Tu t’laisses aller” (“You’ve Let Yourself Go”), a man grows disillusioned by his wife’s diminishing beauty and expanding girth. “La Bohème,” one of his signature songs, was a plaintive ode to lost artistic inspiration.

“Before Aznavour,” the French writer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau once quipped, “despair was unpopular.”

He filled major concert stages from Europe to North Africa to North America and performed in one-man Broadway shows over the decades.

In addition, he starred as a doomed musician in François Truffaut’s crime drama “Shoot the Piano Player” (1960), and appeared in dozens of other films, including the Oscar-winning version of the Günter Grass novel “The Tin Drum” (1979).

Country singer Roy Clark had a best-selling pop hit in 1969 with Mr. Aznavour’s “Yesterday, When I Was Young,” a melancholy contemplation of a fleeting and wasted youth. Mr. Aznavour had one of his biggest English-language successes in the early 1970s with “She,” about the feelings elicited by a mercurial woman:

Elvis Costello’s version of “She” was featured on the soundtrack of the Julia Roberts-Hugh Grant film “Notting Hill” (1999). Ray Charles, Celine Dion, Sting, Tom Jones, Elton John, Liza Minnelli and Plácido Domingo were among the entertainers to record Mr. Aznavour’s songs. He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1996.

Sharmouz Varenagh Aznavourian – different sources use variant spellings of the full name – was born in Paris on May 22, 1924. His parents, with roots in Armenia, had fled to France to escape massacres in Turkey. Charles, as their son became known, grew up in grinding poverty.

His father, by all accounts a fine singer, eked out a living working in restaurants. His mother, who also had been a singer, became a seamstress. Mr. Aznavour soaked up a variety of cultural influences, from American jazz to the Armenian and Russian folk songs and poetry his parents taught him at home.

He abandoned formal schooling at a young age and was performing in theaters and cafés by age 9. During the German occupation in World War II, he sold black-market chocolate and fake silk stockings while also struggling to establish himself as a singer, relying on his own compositions.

“My fundamental reason for writing songs was based on my conviction that the French chanson had insipid lyrics,” Mr. Aznavour once told the BBC. “I wanted to do something new, more truthful and far more to the point.”

Laments such as “J’ai bu” (“I drank”) or “Je hais les Dimanches” (“I Hate Sundays”) were startling – and attracted singers such as Juliette Gréco, a cabaret star known for her deep voice and world-weary style. He also captured the attention of Piaf, who pulled Mr. Aznavour into her entourage as a chauffeur, bag-handler and live-in companion.

He later told The New York Times they had “une amitié amoureuse,” which he said “means more than friendship and less than love.”

As he cobbled together a living as a songwriter for others, including Piaf, Mr. Aznavour found it difficult to emerge as a star in his own right. He did not exude joie de vivre onstage.

“The worst critics were when I first started,” he told Britain’s Daily Mail in 2015. “One wrote, ‘Why did they let a cripple on stage?’ I disturbed everybody. My ugly face, my lack of height, my uncommercial songs. I was told I would never be a success.”

His breakthrough came in 1956 with a revue in Casablanca, where he was embraced by audiences. He was soon headlining at top Parisian venues, leading to record contracts and starring roles in French movies.

He continued to pour out songs. He wrote about a man in love with a deaf-mute woman, rape, illiteracy, traffic accidents, AIDS, urban violence and the slain journalist Daniel Pearl – stories he described as “realities of everyday life.”

He also composed, in 1972, “Comme ils disent,” about a gay man who works as a female impersonator. Known in English as “What Makes a Man a Man?,” it was one of the first songs to present a gay life without innuendo and sarcasm – just an unadorned tale of a lonely man who sees himself as a great artist.

Mr. Aznavour said friends at the time advised him to issue a disclaimer that he was not gay, but he refused. “There are no taboos in art,” he told the London Guardian years later. “Lautrec painted a woman on a chamber pot. Art is art. How can we have less in music?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.