When I first heard about “The Sopranos,” I was reluctant to watch it. I knew this world – two-bit Jersey mobsters, their consiglieri and goomars – way too intimately. As a fledgling reporter, I had covered a mob trial back in the ’80s in Newark and heard my cousin’s name mentioned in the secretly recorded FBI tapes. I’d even written a book, “Five-Finger Discount,” with real characters from my own family – including a murderous grandfather called Beansie – that were eerily similar to David Chase’s creations. How could a TV show capture the world that I genuinely understood from the inside out?

Though I was a huge “Godfather” fan, I hated movies that poked fun at Italian Americans – “My Blue Heaven” and even “Moonstruck,” which I did come to love in time. Italian Americans aren’t all morons existing for your comic pleasure. I had a chip on my shoulder as thick as a slice of Sicilian pizza.

But out of curiosity, I tuned in to “The Sopranos.” From the opening credits, with Tony’s drive out of the Lincoln Tunnel through the urban wasteland where I grew up and into the “safety” of the suburbs, I was hooked. Because of my own life and my family’s hilarious and alarming story, I identified with Tony when he told his therapist, “I find I have to be the sad clown. Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside.”

I wasn’t the only one who identified.

“The Sopranos” was a huge hit with both critics and viewers – here was a family comedy and drama that didn’t insult our intelligence, that told a layered story, punctuated with a smart and varied playlist. Its characters were sometimes dumb, but they were always complex and genuine with an incredible cast led by James Gandolfini, who walked the line between brutal and sensitive every week and made “The Sopranos,” well, sing.

The landscape of television – and American culture – was changing right before our eyes. Television was generally a vast wasteland of laugh tracks and the occasional happy-ending dramedy. But “The Sopranos” raised the bar for narrative storytelling. Tony murdering a Mafia turncoat between stops on a college tour with his daughter, Meadow, shifted our standards on television violence. It paved the road for smart but graphic shows such as “Game of Thrones,” “Boardwalk Empire” and even international hits like “Berlin Babylon.”

Before social media and online video services, “The Sopranos” succeeded on old-fashioned word of mouth and marketing. Viral was still a word associated with the flu. Streaming and binge-watching hadn’t entered our vocabulary. But because of the revolution that “The Sopranos” started, TV would displace film as our main conduit for entertainment.

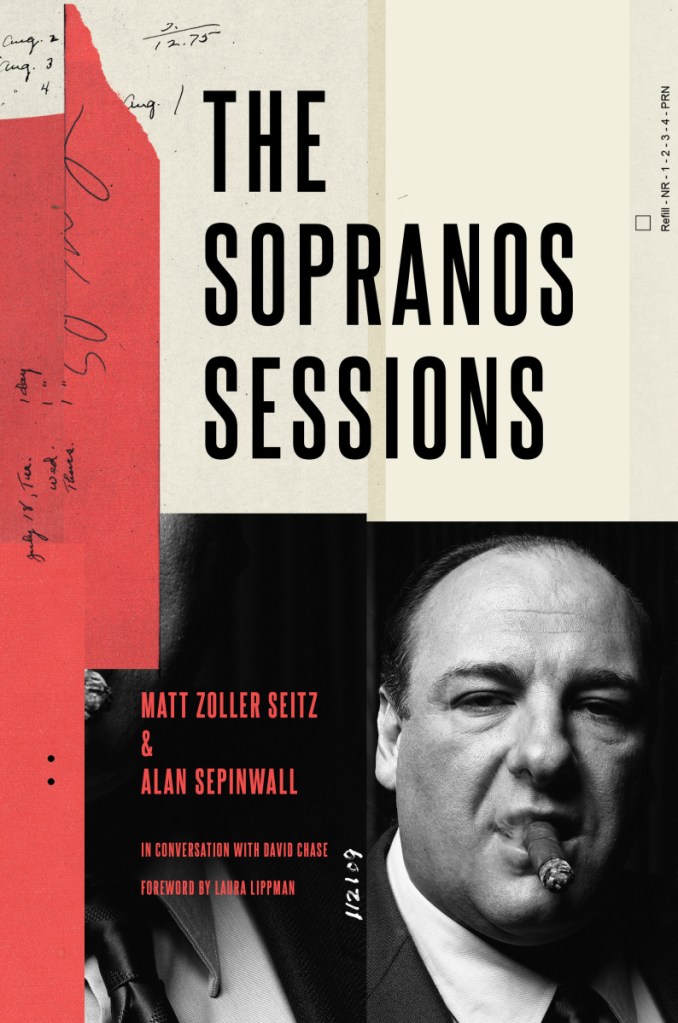

Like most family milestones, it’s hard to believe that 20 years has passed since the first episode of “The Sopranos” aired. To celebrate the anniversary, festivals and other events are being planned, as is a prequel feature film. A dense, all-encompassing book about the show – “The Sopranos Sessions” – has just been released, a psychological and philosophical deep dive written by two former Star-Ledger writers who were there on the ground floor. (The Ledger is the paper Tony memorably picked up in his driveway.)

I approached the book as I did the show, with trepidation. But like Chase and Gandolfini, these guys – Matt Zoller Seitz, TV critic for New York magazine, and Alan Sepinwall, chief TV critic for Rolling Stone – are the real deal. Their analysis of that opening-credits drive – which compares the ride to the evolution of immigrants in American society – is enough reason for any fan to buy this book.

Then there are the exclusive interviews with Chase, who doesn’t talk to many reporters. Brilliantly, they start with the question: Tell us about your mother. (Chase admits he based Tony’s mother, Livia, on her and says actress Nancy Marchand eerily channeled her. “My mother was nuts,” says Chase, “and she obviously did not have a happy childhood.”) There’s also lengthy discussion of that controversial, ambiguous last episode, filmed at Holsten’s, where I have enjoyed the occasional onion ring since the screen went black in 2007. (Chase tries to keep his responses ambiguous.)

The authors explain, in extended “Infinite Jest”like annotations, the actors’ ties to “The Godfather,” “Goodfellas” and the rest of the world that came before and after, and reintroduce us to Livia, Silvio and Carmela and Uncle Junior and Christopher and all the characters who have been standing there all these years in the shadows of our subconscious, waiting to whack us once again. They hit, head on, the Italian American community’s hatred of the show, glorifying gangsters at the expense of all the hard-working Italian Americans. (”I think it did a lot to raise the profile of Italians,” says Chase. “I know they were gangsters and killers, but I think for the right audience, they were very innocent. … they were human beings.”) They call out episodes that alienated viewers, such as the one in Season 3 when a stripper is violently killed.

They discuss Chase’s use of symbolism – eggs as a harbinger of death and the number seven – as well as literary and cinematic allusions, making the show seem even more of a dark masterpiece than we thought. The writers pick apart and analyze, in exhaustive and exhausting detail, each hilarious and disturbing episode of the seven seasons, making you want to go back and watch them all over again.

But I’m not sure I can bring myself to see them again. It would be like going through childbirth again or reliving the pain of adolescence or going through that bad breakup twice. There was beauty there, yeah, but mostly pain and darkness. Could I handle it all again?

Tony is like an old lover you hold dear in your memories but never really see again. The book ends with Chase’s eulogy of Gandolfini, a letter to his dead friend. When I heard Gandolfini died in 2013, I felt the shock that usually comes when a family member passes. For me, it was up there with John Lennon being shot. Because of what he put out there, because of his vulnerability and power, we thought we knew Gandolfini. And Tony.

Maybe I’m afraid to re-watch the show because I’m worried his performance and the series won’t hold up, even though the authors say here that they do.

Television, and storytelling in general, is better because of “The Sopranos.” But so much, too much, has changed for the worse since those days, which we thought – silly us – were so complicated and grave.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.