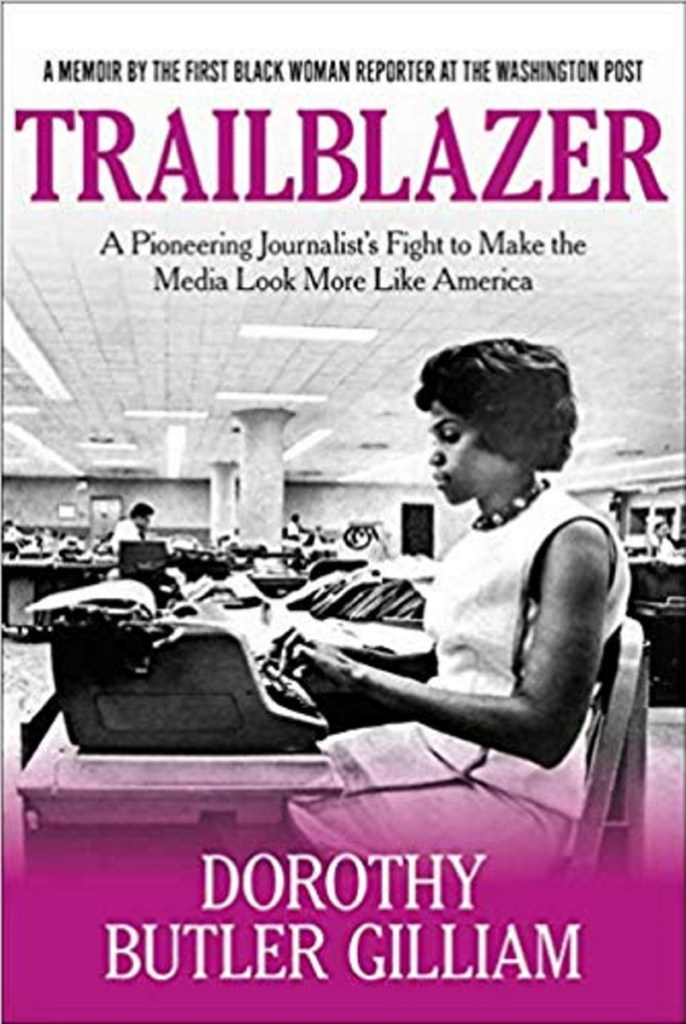

If your mother says she loves you, check it out. Every reporter worth his salt knows that adage, and Dorothy Gilliam, no slouch, practically took that quip to heart. As the first African-American female reporter ever hired by The Washington Post, she followed the rules and then some to survive. “Trailblazer: A Pioneering Journalist’s Fight to Make the Media Look More Like America” is her account of life behind the headlines and beyond.

Gilliam was only 23 when The Post hired her. The year was 1961 and times were fraught: President Kennedy and his attorney general brother were acting like the freedom riders of the civil rights movement didn’t know their place, calling them “‘unpatriotic’ because they were embarrassing the nation on the world stage.” Most of Gilliam’s white colleagues wouldn’t speak to her; taxis wouldn’t stop for her; a black doorman stopped her when she arrived at a fancy apartment building for an interview with a white resident. “The maid’s entrance is around the back,” he told her.

Through it all, Gilliam was intrepid, but she was also isolated, working in a city that wanted to erase her. The newspaper wouldn’t even cover death in the black community – an editor called them “cheap deaths,” unworthy of attention.

“I would sometimes experience panic attacks when I was walking to work,” she writes, “fearing what was happening at the office, what I would encounter there, who would not speak to me.”

Gilliam got started as a reporter in the black press in the 1950s when she was still in high school. She was living in the projects when she began working as a secretary at the Louisville Defender. Her fate was sealed one day when the society editor got sick and she was asked to fill in. She was only 17.

“Suddenly, with no journalism experience and only recently reintroduced to housing with indoor plumbing, I was launched into ‘black society,'” she writes. “I saw Negroes who set their tables with fine china and lead crystal, serving the grandest meals and liquors, entertaining the way I had seen white people do. … I began to see that I could have a ‘bigger’ life.” That bigger life included a job at JET magazine and Ebony in Chicago after college, and then a graduate degree in journalism from Columbia University. She also married visual artist Sam Gilliam and started a family.

Then, in 1968, the Kerner Commission attacked the press for ignoring the black community. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and parts of Washington went up in flames.

The commission “pointed to the media as a visible culprit for ignoring conditions in black communities,” she writes. “The negative images white America had of African-Americans were the fault of a biased white media.”

She was keenly aware of her own ability to tell black stories, and she was in the right place at the right time. She overcame racism and sexism and went on to become a columnist.

While much of this book is concerned with historical events, her personal experience burns at its core. Gilliam’s own story, her interiority, lights up the page. Her descriptions of growing up – as a preacher’s daughter and the eighth child of 10, suffering through her father’s illness and death, developing an eating disorder and living without indoor plumbing – are all riveting. She also writes about her own internalized racism, reflected in her first editorial for her college newspaper, where she advocated for “a ‘go-slow’ approach to implementing integration.”

“I had arrived at school in the fall of 1955 – psychologically shackled from living nearly eighteen years in the Jim Crow south,” she writes. “I had grown up internalizing feelings of second-class citizenship. … I had been ‘mis-educated.'”

Like many black journalists in the 1970s, she reversed this mind-set and went on to become an advocate and activist. Her journalism career spanned 50 years, and she eventually became the president of the National Association of Black Journalists.

One only wishes Gilliam gave herself permission to write more about the price of her ascent – the challenges of marriage and divorce, her husband’s mental illness and infidelity and the colorism she and her daughters faced. Regardless, a trailblazer she is and a trailblazer she always will be. This book is testament to that.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.