In 1997, a few grams of Timothy Leary’s ashes were blasted into orbit aboard a Pegasus rocket. As a metaphor of the grand showman’s spaced-out antics, it was the perfect conclusion. And if Leary’s expanded consciousness is still out there peering down on planet Earth, he must be wondering what took T.C. Boyle so long to write a novel about him.

Boyle is America’s bard of historical frauds and pipe dreams. He’s written about the cereal promoter John Harvey Kellogg and the sexologist Alfred Kinsey. He’s studied the hippies at Morning Star Ranch and the terranauts of Biosphere 2. Again and again, he brings his skeptical eye to the stories of charismatic people devoted to bending society around the pole of their own mania.

Leary, the infamous promoter of LSD, the guru whom Richard Nixon once called “the most dangerous man in America,” feels like a character God cooked up in a lab specifically for T.C. Boyle.

With a Ph.D. in psychology – not a medical degree – Leary first gained notoriety in the early 1960s at Harvard where he made wild claims for the therapeutic and transformative effects of hallucinogens. Under the influence, prisoners were reformed and students saw God! But as Tom Wolfe wrote in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” Leary was actually just “french-frying the brains of Harvard boys.” When the faculty turned against him, Leary began a decades-long trip – sometimes as a fugitive – that took him in and out of prison, where he once chatted with Charles Manson; through the bedrooms of the rich and famous, including John Lennon and Yoko Ono; and around the world, pursued and protected by such fantastical figures as G. Gordon Liddy and Eldridge Cleaver. American authorities finally caught him in Kabul.

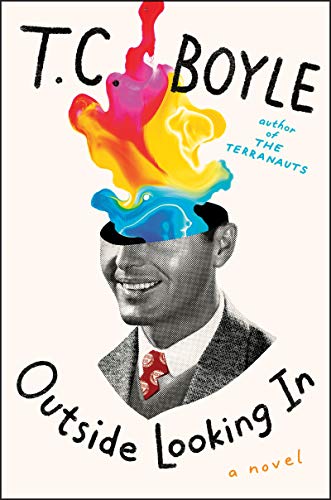

Many of those shenanigans still hover in the zeitgeist, and many more are exhaustively detailed in Robert Greenfield’s 2006 biography, “Timothy Leary.” No fiction writer could compete straight on with the full spectrum of that psychedelic life. But for his novel “Outside Looking In,” Boyle wisely keeps to Leary’s early career. And besides, he isn’t interested so much in staring directly at Leary as at the shadow this great burning ball of gas casts on ordinary people caught in its orbit.

The protagonist of “Outside Looking In” is a hard-working young man named Fitz Loney, a fictional character whom Boyle knits seamlessly into the historical craziness of the era. Despite having a wife and young son, Fitz has quit his job as a high school psychologist to pursue a Ph.D. at Harvard under the tutelage of a “shining star” named Tim Leary. From the moment Boyle introduces Fitz, he seems an unlikely disciple, a very unmerry prankster. Indeed, before he got to Harvard, the riskiest thing Fitz had ever ingested was vodka with orange juice: “He hadn’t come to grad school for God or mysticism or mind expansion or whatever they were calling it,” Boyle writes, “but for a degree that would lead to a job that would pay his bills and get him a house and a car that actually started up when you inserted the key and put your foot down on the gas pedal.”

Such square attitudes make Fitz reluctant to turn on, tune in and drop out, but the politics of graduate school require him to participate in his adviser’s research. Boyle portrays Leary as a blend of cheerfulness and manipulation, and he’s attentive to the new lingo that Leary and his disciples are slipping into the language – somewhere between science and mysticism – like “the Fifth Freedom, the freedom to explore your own mind.” Sensing Fitz’s hesitancy to jump in, Leary tells him, “It’s hard to let go, hard to evolve, but that’s what we’re doing here, that’s what the project is all about. We’re explorers, right? Going where nobody has gone before.”

Where’s Nancy Reagan when you need her?

Leary’s “experiments” involve weekly sessions at his house where sympathetic faculty members, sycophantic grad students and various hangers-on come together, drop acid and have mind-blowing sex. Boyle re-creates those sessions in all their supercool flimflammery, along with the haze of legitimacy meant to obscure Leary’s violations of basic medical procedure. “It was research, that was all, only research,” Fitz tells himself as he scarfs down pills from a bottle marked “POISON.” But he’s astute enough to know that what’s happening here has no clinical justification, and we can feel Boyle’s censorious attitude pumping through these pages like a naloxone drip.

That’s not to say that “Outside Looking In” is one long buzzkill, but it is a farce laced with tragedy: the story of a good man’s increasingly tortuous moral gymnastics. “Tim was unorthodox, but that was the whole attraction, wasn’t it?” Fitz asks himself. “How could you be an iconoclast without tipping over statues, stepping on toes?” Eventually, Leary, the mesmeric adviser, will announce that he’s “bored with the science game because the science game was too confining and had no place in it for pure experience,” but by that time, Fitz is too doped up to admit what’s happening to him.

There’s plenty of zany comedy here – including a poo-flinging monkey and a sombrero from which Leary picks the names of sex partners like some kind of libidinous predecessor of the sorting hat in “Harry Potter.” The humor, though, is tempered by the damage that Leary wreaks on Fitz and his family. One of the most heartbreaking sections of the novel focuses on Fitz’s wife, Joanie, who initially finds Leary and his “sacrament” an exciting release from the drudgery of her life. Ensconced with the “psychonauts” in a 64-room mansion in Millbrook, N.Y., Joanie imagines that this is “the moment all her life had been building toward.” What could go wrong when everybody – except Leary – is asked to “leave your ego at the door”? Surely, those 12 bathrooms will clean themselves, and meals will appear through the power of positive energy. All the children will be fine exploring their independence while the parents trip. “It was an idyll,” Joanie thinks, “her erotic life a dream of the flesh and the mind both.”

Boyle may sympathize with Fitz and his wife as they slide toward oblivion on Leary’s snake oil, but he’s a merciless chronicler of their descent. And all along the edges of “Outside Looking In,” we can see signs of the country growing both more alarmed and more enchanted by the promise of a drug-induced nirvana. Although Boyle resists the temptation to make any overt allusions to our current Oxycontin death spiral, the implications are clear.

This is a superbly paced novel that manages to feel simultaneously suspenseful and inevitable. As Boyle has suggested in the past – particularly in “Drop City” (2003) – “casting off societally imposed strictures” is often a recipe for loneliness at best, abuse at worst. Yes, it’s a drag, man, but any enlightenment that comes from a pill isn’t worth having. Better to get high on a good book.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.