HALLOWELL — Two quarries with more than 200 years of history in Hallowell’s greatest industry — and a gathering place for locals — are for sale.

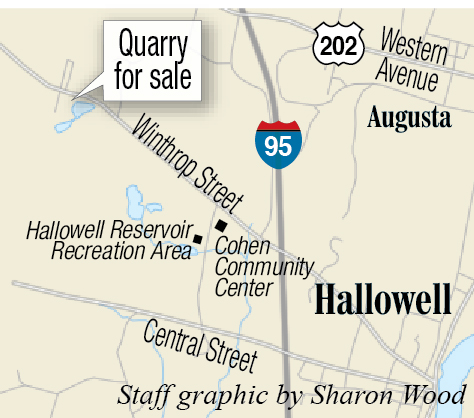

Owner Leonard Nason Jr., 86, has owned the 78-acre property on which the quarries are located, accessible from Winthrop Street near the Manchester line, for more than 50 years. He decided to list it for sale when it became too much for him to manage. The active quarries have an asking price of $5.5 million, Nason said, and a lot more granite to be mined.

“You could get your money right back,” he said of the asking price.

Nason, the owner of Hallowell Granite Works, plans to keep his Winthrop Street home near the quarries and other granite deposits in Manchester he owns.

The quarries were abandoned in the mid-1900s after the rise of concrete as a building material. They were dormant for eight decades until Nason started work there again in 2010. He has mined them sporadically since. He said he is pulling grout stone out now, but some deposits are untouched. Hallowell’s granite is still sought after because of its light gray color, according to Nason.

This view, seen Thursday, shows one of the two granite quarries for sale in Hallowell. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

In 2010, about 170 people attended a Kennebec Historical Society tour of the quarries, where they reminisced about swimming in the Stinchfield Quarry, the one closer to Winthrop street, during its dormant period. Nason has since posted the property, and swimming is banned there. Popular spots to jump in, including “The 60,” a ledge about 60 feet above the water’s surface, are now tagged with graffiti. Nason said Thursday he has thought about draining it again, but he resisted because the quarry is home to fish and the water to clear and clean.

“The state made me check 10 … samples of water,” Nason said. “They said (the) water is cleaner than Poland Spring’s. They said I’m in the wrong business.”

Tim Holland, left, measures a shelf of granite Oct. 20, 2010, in one of Leonard Nason’s Hallowell quarries with his brother, Bobby. Tim, Bobby and Bill Holland, of Jonesboro, were extricating blocks of granite from the quarry for J.C. Stone Inc., of Washington. Kennebec Journal photo by Andy Molloy

The quarry was drained ahead of 2010 work, exposing a number of strange items. Nason said items as big as cars and snowmobiles and as small as class rings were uncovered.

“I gave 19 cars to the state,” he said. “I think they wanted them out of there. I don’t get involved with that.”

“One little girl came to me with quite a little bit of coin and said, ‘Mr. Nason, I want to talk to you,” Nason added. “She said, ‘I got this coin. I think I should give it to you.’ I said, ‘Finder’s keepers, honey. Put it in your pocket.'”

Cornice stones at the Quincy Market, seen in 2010, were created from Hallowell granite. Photo courtesy of Sam Webber

“Historic Hallowell,” a book published by Hallowell’s Centennial Committee and written by Katherine Snell and Vincent Ledew in 1962, said Nason’s roadside quarry was first known as Haines’ Ledge, owned by John Haines, and then his son, Jonathan, where six or seven men worked to provide cornice stones for Boston’s Quincy Market from 1815 to 1827. In 1829, granite from the quarry was used to build the State House in Augusta.

The quarry was sold to a group of Hallowell and Gardiner businessmen in 1828, then to A.G. Stinchfield, whose name it bears now. Stinchfield sold it to Joseph R. Bodwell, Charles Wilson and William Wilson in 1865, according to Snell and Ledew. The neighboring quarry immediately to the southwest, the Longfellow Quarry, was owned at one point by Gov. John Hubbard and Samuel Longfellow, after whom that quarry is named.

The business expanded under Bodwell’s lead, according to City Historian Sam Webber. He said the Bodwell granite works was the largest employer in Hallowell from after the Civil War until the early 1900s.

“It brought skilled and unskilled granite workers to Hallowell, most of them … (from) Italy, who were skilled cutters in monument and statuary,” Webber said. “Many descendants live in Hallowell today.”

Bodwell’s son took over after the death in 1887 of his father, who by that time had become Maine’s governor. A decade later, 500 people were employed in stonework and related fields in Hallowell. The business boomed again from 1904 to 1906, when hundreds of statues, columns and monuments were sent all over the country. According to Ledew and Snell, it was claimed by a Hallowell Board of Trade dinner in 1909 that “Hallowell’s payroll was greater than any city in Maine.”

A number of prominent buildings across the country were made of Hallowell granite, including the Chicago post office, the Gettysburg monuments in Texas, New York’s Capitol and New York’s Manhattan Bridge Plaza.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.