Joseph Merrick, a Victorian-era celebrity who became known as the Elephant Man, led a difficult life because of his physical deformities, whose cause remains a mystery to this day. But now, thanks to research by one author, we know he may have found some semblance of rest.

Merrick died on April 11, 1890, at age 27. But his story of struggle and perseverance has made him an iconic figure in British history. He has been portrayed on screen and stage by the likes of John Hurt, Mark Hamill, Bradley Cooper and no less an icon than David Bowie.

Merrick’s skeleton is kept at Queen Mary University of London, where students and medical faculty members can request to view it. But Joanne Vigor-Mungovin, who in 2016 published “Joseph: The Life, Times, and Places of the Elephant Man,” believes she has located the plot at the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium where his soft-tissue remains were buried.

Though she told The Washington Post that she could not “be 100 percent sure” the grave she found belonged to Merrick, she said “everything pinpoints towards Joseph.” She said she worked with the cemetery’s leadership to search burial records that matched his name, as well as the time frame and circumstances of his death.

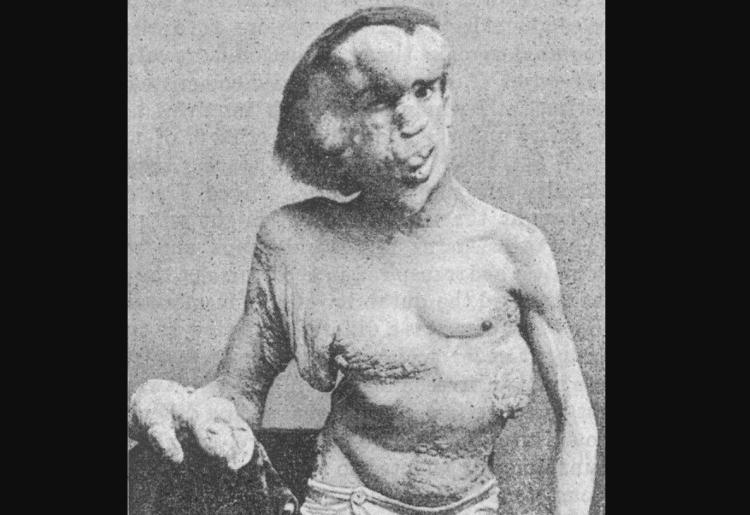

Born in 1862 in Leicester, England, Merrick initially appeared to be a healthy child but developed deformities at a young age. His head and right hand grew to immense proportions, his skeleton became contorted, and he had difficulty speaking and walking. He faced lifelong discrimination for his appearance, but it also brought him fame and a place in history.

After a challenging childhood, Merrick found employment at a workhouse in Leicester for several years but eventually decided he could attempt to make a living by exhibiting himself to audiences. He contacted a local comedian, who put him on tour before he eventually found his way to London in 1884. He began working for a man named Tom Norman, who specialized in displaying “freaks and novelties,” according to “The True History of the Elephant Man” by Michael Howell and Peter Ford.

Norman rented a shop in Whitechapel to exhibit Merrick and hung a garish banner outside advertising his deformities. It was there he was discovered by a young doctor at London Hospital named Frederick Treves, who became a key figure in Merrick’s life. Treves brought him to the hospital to examine him, where he wrote that Merrick was “shy, confused, not a little frightened and evidently much cowed,” according to Howell and Ford. Treves took measurements of Merrick’s features and later exhibited him to fellow medical professionals.

After Merrick allowed Treves to conduct initial studies, the two parted ways, and Merrick went on a disastrous European tour, where he faced ridicule and assault because of his features. He eventually returned to England, distraught and in worse condition than ever. Treves found him in a police station “so huddled up and so helpless looking,” he wrote in his 1923 memoir, “The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences.”

Treves provided him with a room at London Hospital, where medical staff looked after him, and the two grew close. It was during this time that his fame increased; celebrities raised money for his care, he was visited by members of British society, and at one point he met Alexandra, Princess of Wales.

His death in 1890 was officially ruled to have been caused by asphyxia, which occurred when he attempted to lie down to sleep. Treves conducted an autopsy and preserved the skeleton. But it was not clear what happened to Merrick’s soft-tissue remains.

Mungovin, 47, hails from Merrick’s hometown, Leicester, and works at its namesake cathedral. Her research on the Elephant Man was spurred by her fascination with her city’s history, and she said she felt that searching for his remains was “something I had to do.”

“Knowing that he had a Christian burial and it was on consecrated ground, it made you feel better,” she said. “I did this because I want him to rest in peace.”

She is not the only one who has hoped for such a conclusion for Merrick; campaigners have asked for his skeleton to receive a Christian burial in Leicester.

At an April event for the Whitechapel Society, a London historical organization dedicated to studying the murders of 11 women who are believed to have been slain by Jack the Ripper, someone in attendance asked her to guess where Merrick’s other remains were located. Knowing that the killings took place just two years before his demise, she offhandedly guessed that he would have been buried in the same location as some of the murdered women.

Mungovin said that hunch led her to search the City of London Cemetery’s website for death records. And there was his name: Joseph Merrick.

Mungovin worked with Gary Burks, the superintendent and registrar of the cemetery, who pulled additional records that bolstered the conclusion that the person buried at the cemetery was very likely Merrick. The burial took place on April 24, 1890, just a few days after he died, on the 11th. His residence was listed as London Hospital, where he lived.

On Friday, Mungovin finally went to visit Merrick’s newly discovered grave.

“It was poignant,” Mungovin said. “I said a little prayer and laid some flowers.”

Hi vigor @Berliozjo at the plot where Joseph Merricks remains were laid to rest. The story now @BBCLeicester pic.twitter.com/wiRGIVYv5w

— Dave Andrews DL (@davearadio) May 5, 2019

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.