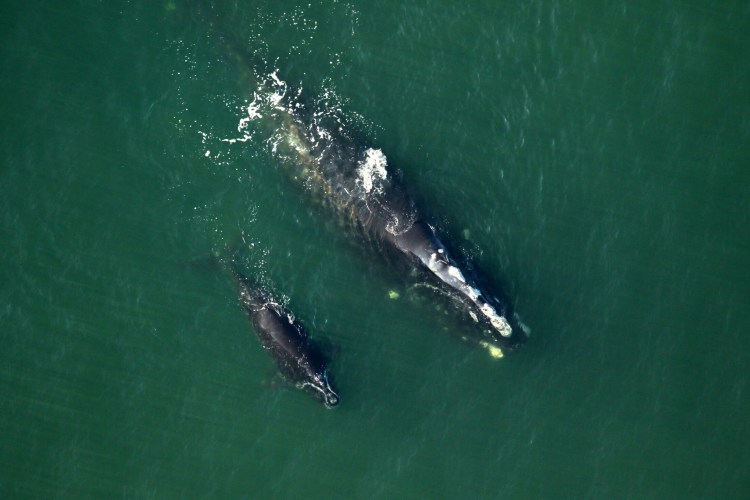

DAYTONA BEACH, Fla. — In February 2016, East Central Florida animal lovers were riveted by an endangered right whale nicknamed Clipper and her baby.

Clipper gave birth to the calf off Florida’s east coast, then found her way into Sebastian Inlet, giving many people their first look at two of the massive, endangered whales. This week, right whale biologists and scientists gathered around her body on a distant beach at Grand Etang, Quebec.

She is one of six whales found dead in June in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. Clipper’s story illustrates the highs and lows of the efforts in the United States and Canada to save the critically endangered animals.

Jim Hain, senior scientist and program leader for the Marineland Right Whale Project, fears the whales may have reached “a tipping point.”

A network of 200 volunteers in Volusia, Flagler and Brevard counties eagerly watch the ocean each winter hoping for a glimpse of any whale, but especially a female right whale with a new calf. Word of a sighting or a new calf ripples quickly through the community.

Whale calving has dropped off dramatically off Florida’s coast in recent years, bottoming out with no new calves in 2018. but seven calves were reported this winter, raising hopes that perhaps the whale calving would begin returning to its former numbers. But whale scientists cautioned not to get too excited.

Turns out they were right.

The jubilation about the seven calves quickly dissolved into despair as each new dead whale was discovered this summer. A seventh whale has been reported entangled in fishing gear. Canadian and United States authorities have been flying aerial surveillance in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, to try to spot the whales and warn shipping traffic of their locations.

This week that surveillance effort was “enhanced,” Canadian authorities said, so they could search for the entangled whale. At least three of the six dead whales were victims of apparent vessel strikes, said researchers with the Marineland Right Whale Project and the New England Aquarium.

The results of a fourth necropsy were inconclusive. Officials with Fisheries Oceans Canada, collaborating with a network of universities and agencies, have completed necropsies on four of the six whales. The outcome of Clipper’s necropsy was announced Tuesday: “death due to blunt trauma, consistent with vessel strike.”

She was buried in a landfill in Gaspe, Quebec. A 10-knot speed restriction implemented by the Canadian government where she was found is still in place. Four of the dead whales were females. Two of them had been producing calves, and two were old enough to produce calves but had not yet given birth.

“We can’t kill our females before they ever even replace themselves,” said Julie Albert, right whale hotline coordinator for the Marine Resources Council, who helps train local volunteers to watch for the whales. Like many right whales, Clipper’s body carried scars from previous encounters with vessels. She was named for an injury where a portion of her right fluke had been severed or clipped in a vessel strike before she was first spotted off Florida in 2004, said Jim Hain.

Twelve years later, in 2016, she was seen with her first calf, said Hain. She was photographed about a mile off Ponce Inlet.

Albert clearly remembers the excitement around Clipper’s visit in the winter of 2016.

“That was huge,” she said. “It was an incredible learning experience, not just for the public, but the marine mammal people as well.”

People were driving “from very long distances” to see the whale and her calf, Albert said. She was also seen off Ormond Beach and South Daytona, said Hain.

“The frequent sightings in 2016 meant that many volunteers with both the Marineland Right Whale Project and the Marine Resources Council had a connection with this whale.” The deaths are all the more concerning for whale researchers when considered in the context of the births and deaths among the right whales since 2016.

“With only two calves born in 2016 (one of them Clipper’s), 13 born in 2017, no calves born in 2018, and seven born in 2019 held against the 17 deaths in 2017, and the six deaths and an entanglement so far in 2019, we have to accept that we are faced with a tipping point,” Hain said. That’s “a net loss to the population.”

Right whale scientists have grown increasingly concerned about the calving rate, which may be influenced by the amount of food available to the female whales.

But this summer’s deaths particularly sting “for the scientists and volunteers working in Florida, who were cautiously optimistic as of March 2019 when seven calves were tallied for the season,” Hain said.

“While the seven were fewer than might be desirable, this was seen as perhaps the beginning of a rebound or upward trend. Now, in July 2019, even the most optimistic of us will have to face the reality,” he said. “Thoughtful, collaborative, and renewed efforts are required for the successful coexistence of humans and this endangered and symbolic whale species.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.