The proportion of Americans without health insurance grew significantly last year for the first time this decade, even as the economy’s strength pushed down the poverty level to its lowest point since 2001, according to new federal data.

The findings released Tuesday, based on a large U.S. Census Bureau survey, reverse the trend that began when the Affordable Care Act expanded opportunities for poor and some middle-income people to get affordable coverage.

Taken together with other reported measures of Americans’ well-being, the census data paint a portrait of an economy pulled in different directions, with a falling poverty rate but also high inequality and a growing cadre of people at financial risk because they do not have health coverage.

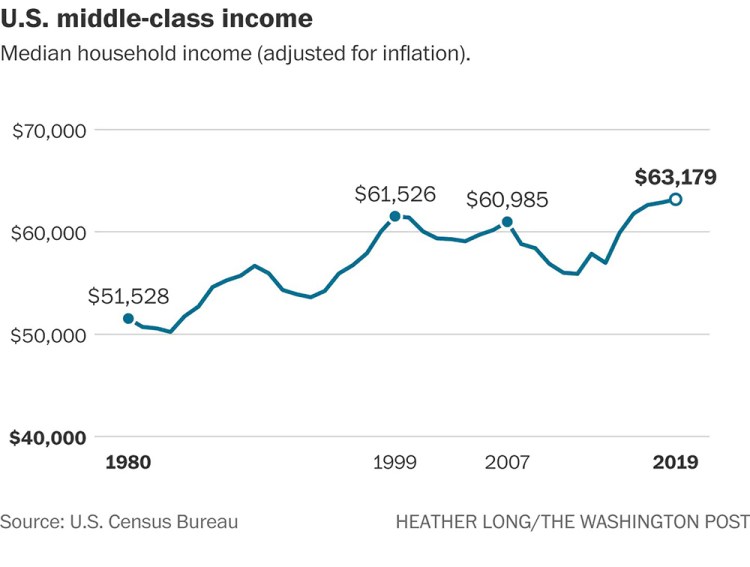

As more Americans found jobs, the poverty rate fell last year to its lowest level since 2001 and middle-class income inched higher. Median U.S. income – the point at which half of U.S. families more and half earn less – topped $63,000 for the first time, although it was roughly the same level as it was in 1999, after adjusting for inflation.

“Median household income today is right where it was in 1999. We’ve seen two decades with no progress for the middle class,” said University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers. “The economy is producing more than before, but the gains aren’t being shared equally.”

The data showed that incomes rose substantially in big cities last year but declined in smaller ones. And poverty rose for adults over 25 without high school diplomas.

“Some of the folks who fueled the Trump candidacy and presidency still aren’t doing great,” said Matt Weidinger, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who watches poverty trends closely.

With health care already a central issue in the 2020 presidential campaigns and a prime voter concern, meanwhile, the fresh evidence that insurance is slipping further out of Americans’ reach is virtually certain to escalate partisan warring about Americans’ access to affordable coverage.

The uninsured rate rose as well in 2018, marking the first time since 2009 that both the number of Americans without coverage and the uninsurance rate rose significantly from the year before.

The change was driven primarily by a decrease in public insurance for the poor, with enrollment in Medicaid dropping by 0.7 percent, the data show. The uninsured rate spiked especially among adults who are Hispanic and foreign-born, with the increase in uninsured among both groups three times the national average. Coverage also dwindled among children who are Hispanic and naturalized citizens.

Health policy experts interpreted those patterns as evidence of a chilling effect from the Trump administration’s efforts to restrict several forms of public assistance, including Medicaid, for immigrants seeking to remain in the United States. In addition, some state have been clamping down on eligibility rules for Medicaid.

“The word has gone out if you use Medicaid, then you are a public charge and you’re liable not to get a green card,” said Sara Rosenbaum, a George Washington University health law and policy professor, who called the patterns of health coverage for immigrant children “alarm bell territory.”

“People are not only not enrolling, they are coming in (to Medicaid offices) and asking to be disenrolled.” Rosenbaum said.

Health insurance has long been recognized as crucial to people’s ability to get medical care when they need it. The availability of insurance is influenced by a variety of factors, including economic conditions, because most insured U.S. residents get their health plans through an employer. In recent years, however, both supporters and opponents of the ACA have looked at Census’ yearly insurance data as a portrait of how well the law is working.

Expanding insurance access was a main goal of the ACA, the statute forged by Democrats nearly a decade ago that has reshaped much of the health care system. President Trump and other Republicans contend the law is fatally flawed, while Democrats maintain it has been undermined by recent GOP policies.

As Trump works to dismantle the law and liberal Democratic candidates seek to replace it with a government-financed health-care system, both sides can find ammunition for their interpretation of why the nation’s uninsured rate has started rising again.

Republicans point to how, as premiums escalate, fewer people buy health plans through the ACA’s marketplaces unless they qualify for federal subsidies. Democrats point to how major tax changes, adopted by a Republican Congress at the end of 2017, eliminated the financial penalty for those who violate the ACA’s requirement that most Americans carry health insurance – removing one motivation to stay insured.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., a candidate who has long called for “Medicare-for-all,” tweeted on Tuesday, “Mr. Trump lied. He promised to strengthen health care – instead, he has done everything he can to sabotage the Affordable Care Act. The result: Nearly two million people joined the ranks of the uninsured last year.”

A consistent decline in the number of uninsured Americans that began in 2011 actually stopped in 2017, according to census data, with about 400,000 more people than in 2016 reporting they lacked coverage. But that did not amount to a statistically significant change in the uninsured rate.

The new figures for 2018 show that the uninsured rate increased to 8.5 percent of the population from 7.9 percent the year before. In contrast, some 9 million Americans gained coverage between 2013 and 2014, the year that Medicaid expanded in many states and ACA insurance marketplaces opened for individuals and families unable to get affordable health plans through work.

Tuesday’s data make clear that the contraction of insurance has been broad. Around the country, insurance coverage worsened in eight states and improved in three states. For the first time, the Census Bureau broke out the proportion of Americans buying health plans through the health law’s insurance marketplaces. They show that 3.3 percent of people last year got their coverage through such a marketplace. The breakout reinforces how the ACA’s health plans, while attracting considerable political attention, account for only a fraction of the nation’s health insurance.

While Medicaid enrollment fell, the proportion of Americans covered through employer-based insurance did not change significantly. Meanwhile, enrollment in Medicare, the program for elderly and disabled people, grew slightly – probably as a result of the nation’s expanding population of older residents, Census officials said in releasing the data.

The Trump administration cheered the news, meanwhile, that the official U.S. poverty rate fell to 11.8 percent last year (38.1 million people), the lowest since 11.7 percent in 2001, as a sign the president’s policies are working to boost the economy. Businesses have been hiring minority and low-skilled workers at unusually high rates lately, helping give jobs and opportunities to Americans who struggled for years to get a chance.

“Employment is the best way out of poverty,” said Tomas Philipson, acting head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. “President Trump’s critics wrongly assert that government programs and handouts are the only way to lift people out of poverty, but today’s data tells a different story.”

The poverty rate for adults who work full-time all year round is 2.3 percent, much lower than the poverty rate for people who do not work, which is nearly 30 percent.

The fall in the U.S. poverty rate has been driven largely by people moving from part-time to full-time work, helping boost incomes. Last year alone, more than 2 million people found full-time jobs, the Census report said.

“We have found quite a big increase in full-time, year-round work that would tend to bring up incomes for working people,” said Trudi Renwick, an assistant division chief at the Census Bureau.

But income inequality also remains near the highest levels of the past half century, according to census data. Recent wage gains by lower-income workers who have found jobs and benefited from minimum wage increases in many states have not been enough to close the long-running trend of the wealthy seeing far larger income gains than the middle or lower classes.

Income for families earning about $15,000 or less have fallen since 2007, according to the latest Census data, while incomes households bring in about $250,000 a year have grown more than 15 percent.

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.