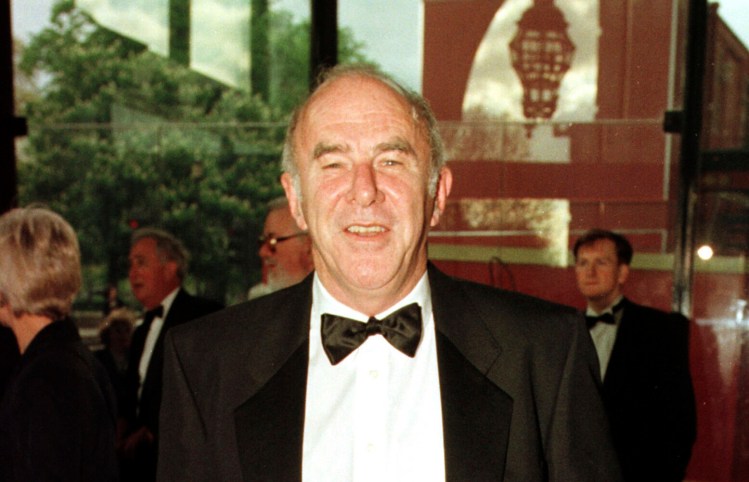

For decades, the Australian-born writer Clive James was a cultural sensation in his adopted Britain as a critic, TV host, memoirist, novelist and poet, and not least for his exuberant, often cunning wit. He memorably described Arnold Schwarzenegger, then a young bodybuilder, as resembling “a brown condom full of walnuts.”

James, who occupied a central place in a London literary coterie that included Christopher Hitchens, Martin Amis and Julian Barnes, was, above all else, a master of incandescent English prose.

Ailing from chronic illnesses in his final years, James couldn’t contain his capacity for wry self-mockery even as he speculated over whether it would be leukemia, kidney disease or emphysema that would cause him to “drop from the twig.”

He died Nov. 24 at his home in Cambridge, England, at age 80. His literary agency, United Agents, announced his death, saying in a statement that James “died almost 10 years after his first terminal diagnosis, and one month after he laid down his pen for the last time.”

James built his early reputation as a television critic before moving to the other side of the camera as a popular TV interviewer and documentarian. On alternating nights, he could be seen joking about absurd Japanese game shows, discussing the state of the Russian novel or jumping into a hot tub with a bevy of Playboy bunnies.

He was often riotously funny as he skewered celebrities with finely honed witticisms. Aging romance novelist Barbara Cartland wore so much makeup, James wrote, that her eyes looked “like the corpses of two crows that had flown into a chalk cliff.”

Describing the intricate costume of actress Diana Rigg in a production of a classical drama, he wrote: “The bodice of her evening gown featured a gold motif that circled each breast before climbing ceilingwards behind her shoulders like a huge menorah. It was a bra mitzvah.”

Yet there was far more to James than sharp observation and clever wordplay. He wrote travel books and song lyrics, appeared onstage in one-man theatrical shows and published poetry in the New Yorker. He wrote four novels, translated Dante’s epic poem “Divine Comedy” and was an authority on Formula One auto racing.

He was immensely learned, yet he detested literary theories and pomposity. He knew eight languages, including Russian, which he learned in order to read the poetry of Pushkin in the original.

James’ five volumes of best-selling memoirs chronicled his rise from a lower-middle-class childhood in Australia to his unlikely fame in London, where he lived in a converted warehouse by the Thames with a library that filled three floors. Late in his career, he published an 876-page book, “Cultural Amnesia,” that Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee called “a crash course in civilization.”

He had no American counterpart.

“When England loses Clive James,” critic Dwight Garner wrote in the New Republic in 2013, “it will be as if a plane had crashed with five or six of its best writers on board.”

James, who said “all I can do is turn a phrase until it catches the light,” seemed incapable of writing an uninteresting sentence. Whether it was a newspaper column, an introduction to a TV segment or one of his more than 30 books, he sought to make his writing entertaining while aspiring to the quality of art.

His comment about the crime novels of Raymond Chandler could just as easily describe James’ own writing: “The thrill of his books was that they were so much better than they needed to be. The style was the substance.”

In any medium, James was compulsively loquacious, turning out essays, memoirs and novels between his countless TV appearances, like a “Benzedrine addict being held at gunpoint.”

His prose had a balanced, aphoristic sense of order, often using a well-placed punchline to make a larger point.

“A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing,” he wrote, in a sentence so memorable it is often mistakenly attributed to psychologist William James. “Those who lack humor are without judgment and should be trusted with nothing.”

Vivian Leopold James was born Oct. 7, 1939, in Sydney. His father, a mechanic who served in the Australian military during World War II, was captured by Japanese forces and held in a prison camp for the duration of the war.

After his release, he was returning to Australia when the airplane he was aboard crashed during a typhoon near the Philippines. There were no survivors. James grew up as his widowed mother’s only child.

She allowed him to change his first name because, as James wrote in “Unreliable Memoirs” (1980), “after Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O’Hara the name became irrevocably a girl’s name no matter how you spelled it.” He chose Clive from a 1942 Tyrone Power movie, “This Above All.”

He graduated from the University of Sydney in 1960, then worked for a Sydney newspaper before sailing for England. He arrived in 1962, equipped only with his native wit and an ambition to be a man of letters.

He received a master’s degree in English literature in 1967 from the University of Cambridge, where he was president of the dramatic society and a member of the university’s competitive quiz team. In 1968, he married Prudence Shaw, a scholar of Italian literature at Cambridge.

After abandoning studies for a doctorate, James made his breakthrough as a writer with a 1972 essay in the Times Literary Supplement about the American literary critic Edmund Wilson.

Although the 10,000-word piece appeared without a byline, the little-known James was soon identified as its author. A congratulatory letter arrived from novelist Graham Greene, who “suggested that I might consider the discursive critical essay as my destined field of operations,” James wrote in one of his memoirs, “North Face of Soho.”

When he began to write about television for the Listener newspaper in 1972 and later for the Observer, James found his voice. Something about the “crystal bucket” – one of his many terms for TV – unleashed a vivid, original style of commentary. His columns were more entertaining than the shows he wrote about.

His aimed his barbs at everything that crossed the flickering tube, from sports announcers to Finnish beer commercials to talk shows. He considered the highbrow dramas of “Masterpiece Theatre” little more than well-dressed twaddle. He much preferred “The Rockford Files.”

He proved so skillful at blending “the apparently antagonistic roles of wiseacre and smart alec,” as he put it, that he was soon invited to appear on television himself. Despite a paunchy physique and balding pate, he spent 20 years on British commercial networks and the BBC as the host of shows, including “Saturday Night Clive,” “Sunday Night Clive” and “The Clive James Show.”

He became familiar to American audiences in the early 1990s, when his eight-part TV documentary for the BBC, “Fame in the 20th Century,” was shown on PBS stations. In the series and an accompanying book, he explored the tangled strands of celebrity, publicity and infamy through such diverse figures as Al Capone, Billy Graham, Joseph Stalin, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Albert Einstein and Muhammad Ali.

From 1989 to 1995, James had a popular travel series on British TV called “Postcards,” in which he rode through the streets of Cairo on a camel, faced down a lion on an African safari and danced the tango in Argentina.

“I studied the language far into the night,” he said while visiting Buenos Aires. “I was looking for the phrase, ‘Is it legal to hold you like this?’ ”

James sustained his multifarious career as a writer and TV personality for decades, before stepping away from his television show in 2001. Six years later, he published what he considered his most ambitious book, “Cultural Amnesia,” an idiosyncratic collection of essays about more than 100 people who left their mark on the 20th century, from obscure German and Russian writers to actor Tony Curtis, jazz great Duke Ellington and historical figures of enlightened thought.

Known as a merry soul who enjoyed food and drink, James seldom revealed much about his private life. He lived in London while his wife stayed in Cambridge, raising their two daughters.

In 2012, a onetime model, Leanne Edelsten, 24 years younger than James, revealed that they had had an eight-year affair. James’ wife barred him from their house. He sought a rapprochement, often through heartfelt poems. They ultimately reconciled, in part through a shared interest in the TV series “Game of Thrones.”

In his final years, James viewed his approaching death with a wistful fatalism. Yet he remained heartily vital, churning out books of poetry and essays while seemingly on his deathbed. He published five books since 2017, with a final book of essays about poetry scheduled for release next year.

“I’ve got a lot done since my death,” he quipped in 2015.

His poem “Japanese Maple,” about a tree visible from his small Cambridge apartment, was published in the New Yorker in 2014, and included this passage:

My daughter’s choice, the maple tree is new.

Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame.

What I must do

Is live to see that. That will end the game

For me, though life continues all the same:

Filling the double doors to bathe my eyes,

A final flood of colors will live on

As my mind dies,

Burned by my vision of a world that shone

So brightly at the last, and then was gone.

Even in farewell, James remained ever quizzical, ever critical, ever quotable.

“I am in the slightly embarrassing position,” he said in 2014, “where I write poems saying I am about to die, and I don’t.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.