There are two parts of the Constitution which are of particular importance at this moment in Washington.

The first is Article II, Section 4, which reads:

“The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The other is Article I, Section 3, which reads in part:

“The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no vote, unless they be equally divided. … The Senate shall have the sole power to try all impeachments. When sitting for that purpose, they shall be on oath or affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two thirds of the members present.”

Americans are likely familiar with the mechanics here. The president can be impeached; if he or she is, the Senate holds a trial. Should two-thirds of the Senate choose to convict, the president may be removed from office.

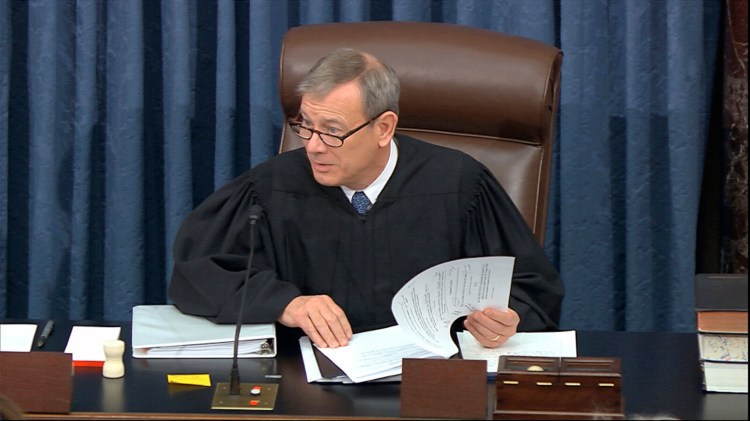

What may be less familiar to observers is the role played by the chief justice of the United States – or at least that may have been less familiar until Tuesday, when John Roberts assumed the dais to oversee the trial of President Trump.

It’s an interesting role for Roberts, who’s used to presiding over legal proceedings. That’s not what the impeachment trial is. Impeachment, instead, is almost entirely political process managed largely by the party with the majority in the chamber. When impeachment loomed in September, The Post spoke with experts to assess how much flexibility Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., had in how the trial might proceed. The assessment? McConnell had enormous flexibility, including simply deciding against having a trial at all.

McConnell’s been fairly direct about making clear his control of the process. On Monday, he introduced proposed boundaries for the trial which constrained opening statements and limited the evidence which might be presented to the Senate. In doing so, he kicked up a storm of opposition – and raised questions about the extent to which Roberts might actually play a moderating role.

To answer those questions, we reached out to Louis Michael Seidman, Carmack Waterhouse professor of constitutional law at Georgetown Law, with whom we’d spoken last year about McConnell’s power.

“As is true of so much else, the Constitution is silent about the things we would like to know – specifically about what the power to ‘preside’ means,” Seidman wrote in an email.

He noted that in the two prior examples of presidential impeachment trials (those of Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1999), the two chief justices took different tacks.

“In the Johnson trial, Chief Justice (Salmon P.) Chase played an active role,” Seidman wrote. “He cast the deciding vote in a number of cases where the Senators were evenly divided and actively directed the trial. In the Clinton trial, Chief Justice (William H.) Rehnquist, on his own characterization, did virtually nothing ‘but did it very well.'”

Where Roberts lands on this spectrum remains to be seen. But Seidman suggests that, in the absence of specific guidelines, Roberts could help guide where the trial goes.

“He could rule on various procedural motions, including responding to objections to testimony or argument, rule on the admissibility of evidence and witnesses, and other matters,” Seidman wrote. “It seems to be common ground, though, that, as with other decisions in the Senate by the presiding officer, he could be overruled by a majority of the Senators.”

Where things get interesting is if Roberts decides to emulate Chase and offer votes of his own as decisions are being made. How might he have the power to do so? As Seidman notes, the Constitution specifies that the chief justice should preside in the case of impeachment taking the place of the vice president. The vice president’s position as president of the Senate – the one who presides – allows his or her casting tie-breaking votes in the chamber. Might not the chief justice’s assumption of that role allow him a similar power?

(If you were suddenly struck with a flash of excitement about the prospect of senators challenging Roberts’s ability to cast a vote – and that challenge then heading to the Supreme Court for adjudication: bad news. Seidman notes that such “political” questions have in the past been determined to be outside the purview of the courts.)

“If the presiding officer had no power,” Seidman wrote, “the Framers might not have been concerned about the Vice President presiding in a case where he would assume office if the President were convicted. But the Chief Justice also has the ‘power’ to keep his head down.”

Seidman expects that Roberts won’t be interested in testing that question. Roberts is both conservative and is interested in avoiding an appearance of partisanship by the Supreme Court. Neither of those suggests a robust interest in interfering with a sharply partisan process.

“If the Democrats think that he will intervene on their side,” Seidman wrote, “they are kidding themselves.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.