Hank Aaron, one of the greatest players in baseball history, who smashed Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record in defiance of threats to his life, and who used his Hall of Fame baseball career as a platform to champion civil rights, died Jan. 22 at 86.

Jonathan Kerber, the Atlanta Braves’ communications manager, confirmed the death but did not provide additional details. Aaron became the 10th member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame to die since April, an unfathomable loss of star power, history and institutional knowledge of the game.

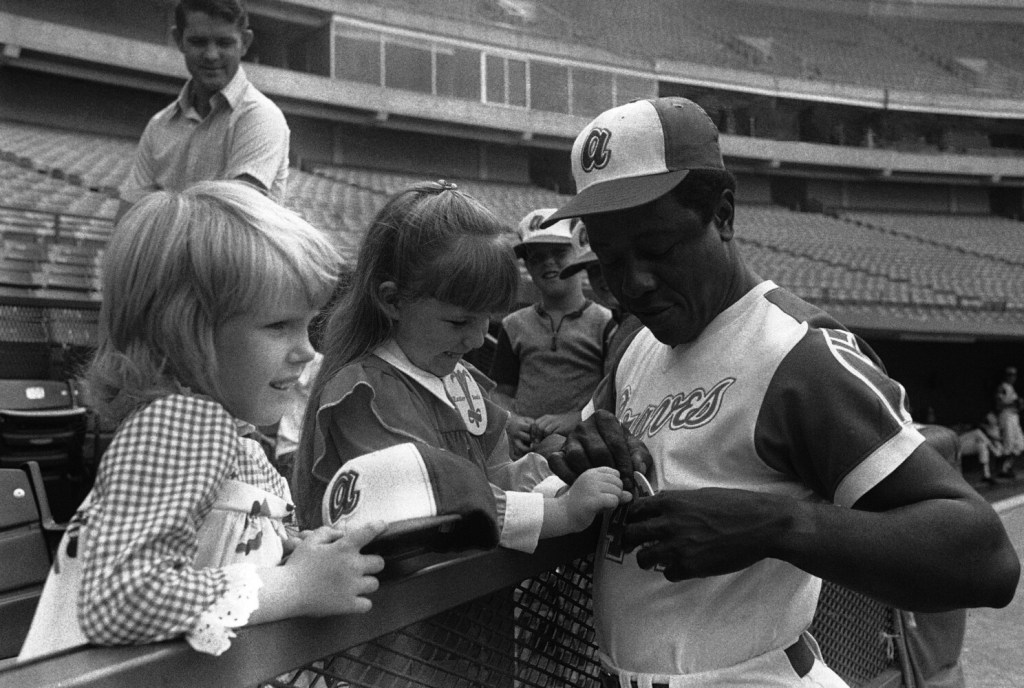

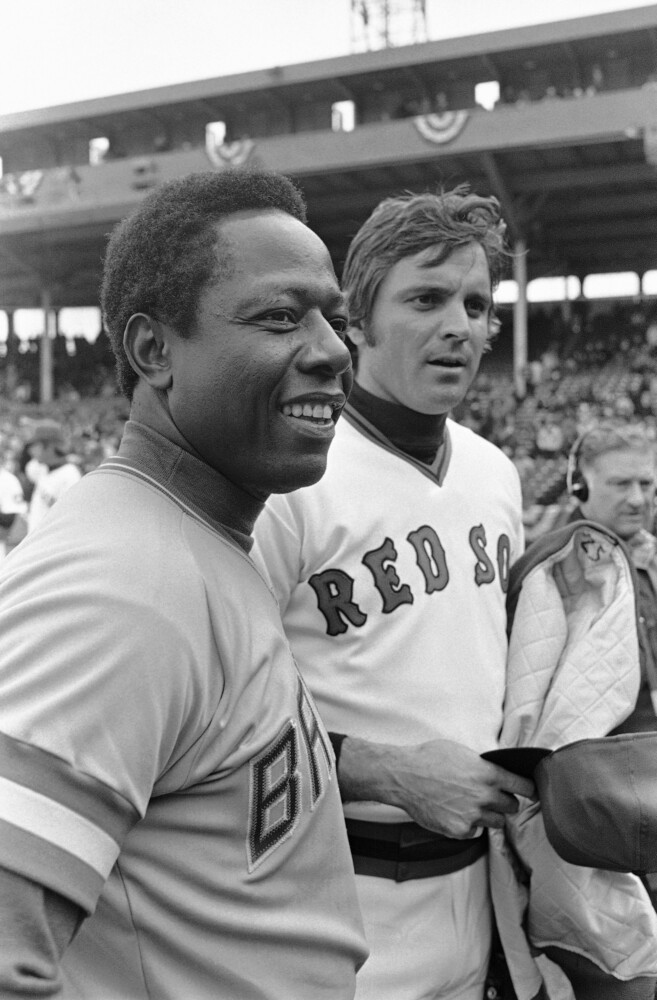

Throughout his 23-year career, spent mostly with the Braves in Milwaukee and then Atlanta, Aaron was admired as a model of steady excellence on the diamond, even though he lacked the swaggering charisma of Ruth or the exuberant flair of his contemporaries Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente.

In 1974, Aaron broke Ruth’s record of 714 home runs before retiring two years later with 755, which remained one of the most hallowed numbers in all of sports for more than 30 years.

Aaron, who preferred to be called Henry but was generally known to baseball fans as Hank or “Hammerin’ Hank,” for his long-ball power, grew up in Alabama and never forgot the jeers he received while playing in the South during the days of segregation.

On the field, few players in history were as skilled at every dimension of the game. Aaron won three Gold Gloves for his defensive play in the outfield and was deceptively fast, once finishing second in stolen bases in 1963 to the speedster Maury Wills.

But it was his quick, compact right-handed swing that made Aaron a superstar, as he compiled one superior year after another. He led the Milwaukee Braves to the World Series championship in 1957, when he was 23, and remained a potent force at the plate into his 40s.

“Throwing a fastball by Henry Aaron,” an opposing pitcher, Curt Simmons, once quipped, “is like trying to sneak the sun past a rooster.”

In 2007, Aaron’s home run record was surpassed by the San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds, who ended his career with 762. Because of Bonds’s alleged use of steroids and performance-enhancing drugs, many baseball fans and writers continued to consider Aaron the true home run champion and an unassailable symbol of fair play and integrity.

“I guess you can call him the people’s home run king,” Hall of Fame player Reggie Jackson told Sports Illustrated in 2007.

Aaron entered the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, the first year he was eligible, and had a career batting average of .305 – higher than those of Mays and another notable contemporary, Mickey Mantle.

• • •

His lifelong inspiration, Aaron said, was Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodger infielder who broke major league baseball’s color barrier in 1947. When Robinson played in an exhibition game in Aaron’s hometown of Mobile, Alabama, it was an unforgettable moment for the 14-year-old future star. Throughout his own career, Aaron recalled the forbearance and strength Robinson showed just in stepping on the field.

“Jackie Robinson had to be bigger than life,” Aaron wrote decades later in Time. “He had to be bigger than the Brooklyn teammates who got up a petition to keep him off the ballclub, bigger than the pitchers who threw at him or the base runners who dug their spikes into his shin, bigger than the bench jockeys who hollered for him to carry their bags and shine their shoes, bigger than the so-called fans who mocked him with mops on their heads and wrote him death threats.”

Robinson had played in the 1940s in the old Negro leagues, a professional circuit of all-Black teams, before joining the Dodgers. Aaron played for one month in 1952 with the Indianapolis Clowns, a touring team of the Negro American League, before signing with the Braves.

When Aaron began playing in the minor leagues, it marked the first time that he had shared the field with white players. When the Braves assigned him to a team in Jacksonville, Florida, in the South Atlantic (or Sally) League, he heard steady taunts from white spectators throughout the South.

After he reached the major leagues in Milwaukee in 1954, Aaron quietly allied himself with the burgeoning civil rights movement. He campaigned for then-Sen. John Kennedy, D-Mass., in Milwaukee in 1960 and was credited with helping the Democratic candidate win the Wisconsin presidential primary.

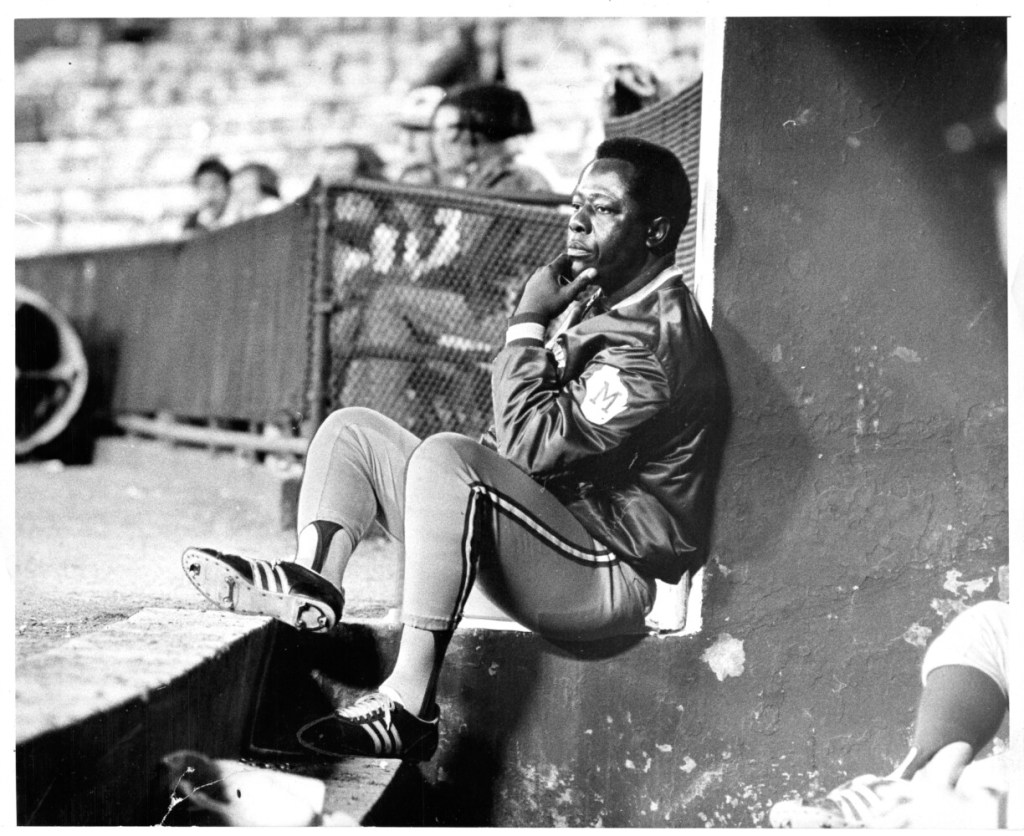

In 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement, the Braves moved to Atlanta, worrying Aaron. “I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again,” he said. “We can go anywhere in Milwaukee. I don’t know what would happen in Atlanta.”

He was the biggest star on a team representing the heart of the old South and became as recognizable in Atlanta as another of the city’s residents, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Henry had never considered himself as important a historical figure as Jackie Robinson,” sports journalist Howard Bryant wrote in “The Last Hero,” a 2010 biography of Aaron, “and yet by twice integrating the South – first in the Sally League and later as the first Black star on the first major league team in the South (during the apex of the civil rights movement, no less) – his road in many ways was no less lonely, and in other ways far more difficult.”

• • •

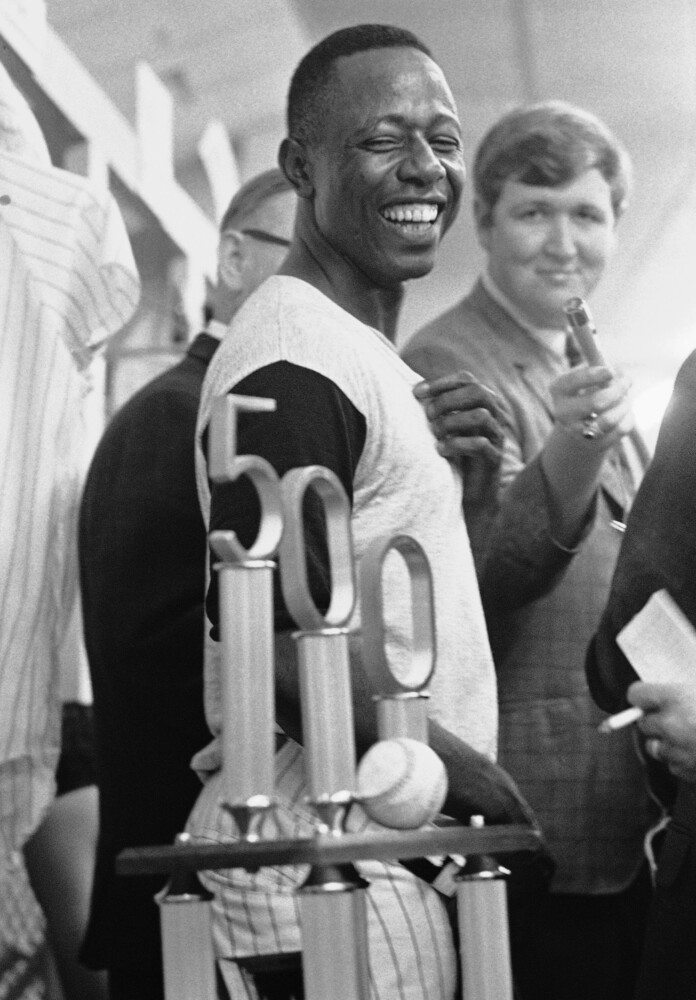

After hitting 40 home runs in 1973, Aaron had a career total of 713, one shy of Ruth’s record. Each home run seemed to come at a deep personal cost.

Since 1972, the U.S. Postal Service noted at the time, Aaron had received more mail than anyone who was not a political figure. Much of it was filled with racism and vile language.

Some of the contents were released to the public. “If you come close to Babe Ruth’s 714 homers,” one letter said, “I have a contract out on you. Over 700, and you can consider yourself punctured with a .22 shell.” Another read, “My gun is watching your every black move.”

A security team accompanied Aaron at all times, his daughter received police protection while attending college, and the FBI looked into some of the more extreme threats. Aaron kept the letters as a reminder of his lonely, dangerous pursuit.

“The Ruth chase should have been the greatest period of my life, and it was the worst,” Aaron wrote in his 1991 autobiography, “I Had a Hammer.” “I couldn’t believe there was so much hatred in people. It’s something I’m still trying to get over, and maybe I never will.”

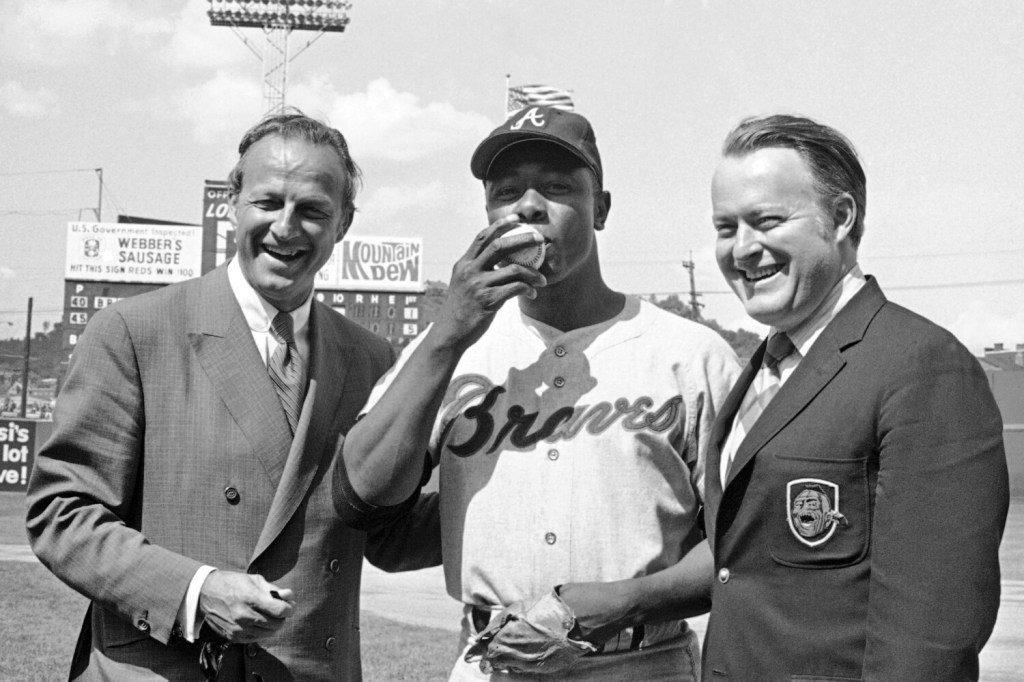

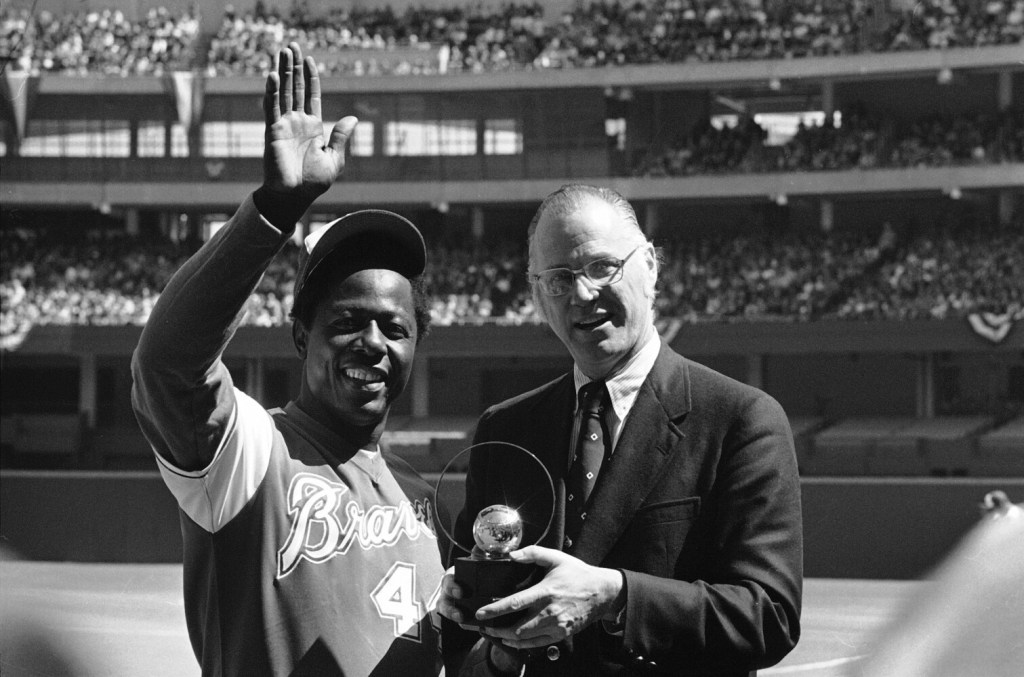

At the beginning of the 1974 season, the Braves wanted to hold Aaron out of the opening three-game series in Cincinnati to allow him to break the record in Atlanta. Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn stepped in and ruled that every team should put its best players on the field and strongly suggested that the Braves comply.

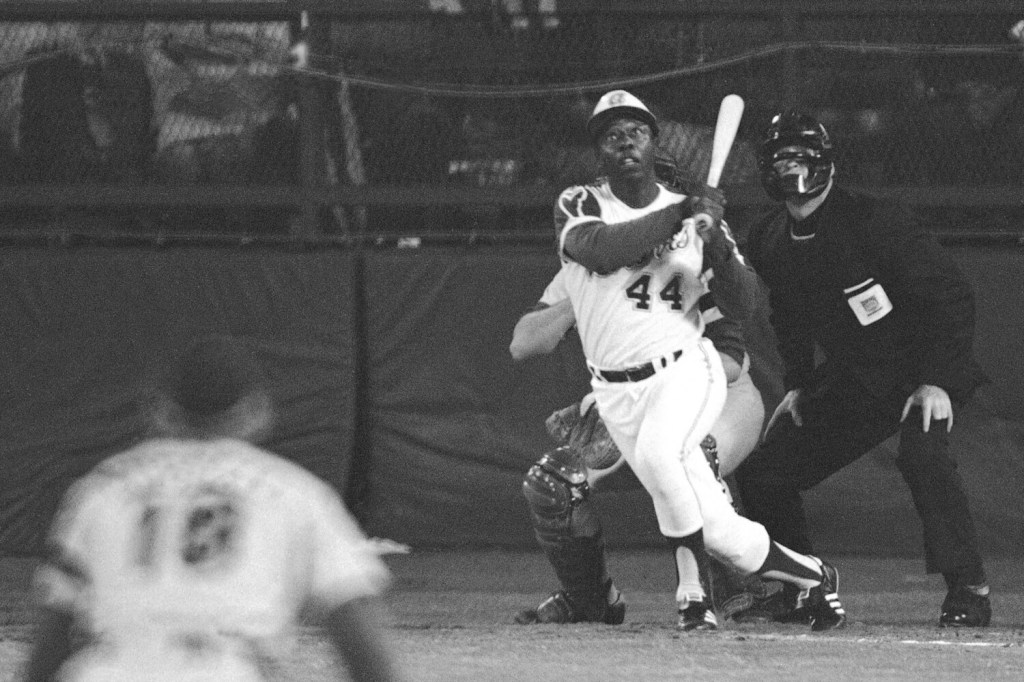

Aaron wasted no time in tying the record, slugging his 714th home run in his first at-bat on Opening Day, off the Reds’ Jack Billingham. He sat out the second game of the series and was held hitless in the third.

The Braves then went home to face the Los Angeles Dodgers, setting a new attendance record of 53,775 for the first game of the series, on April 8, 1974.

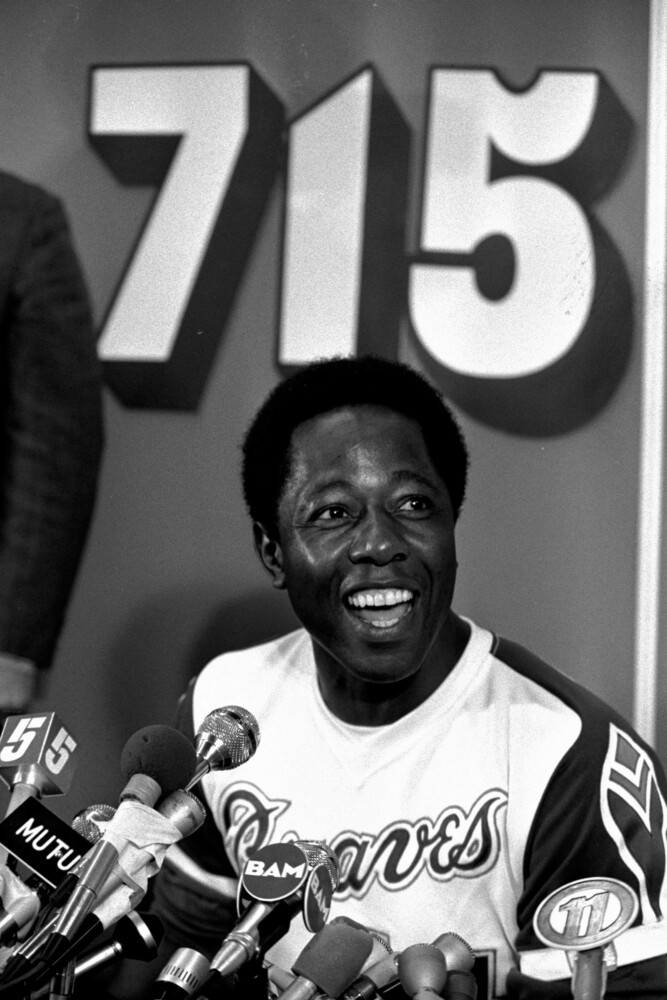

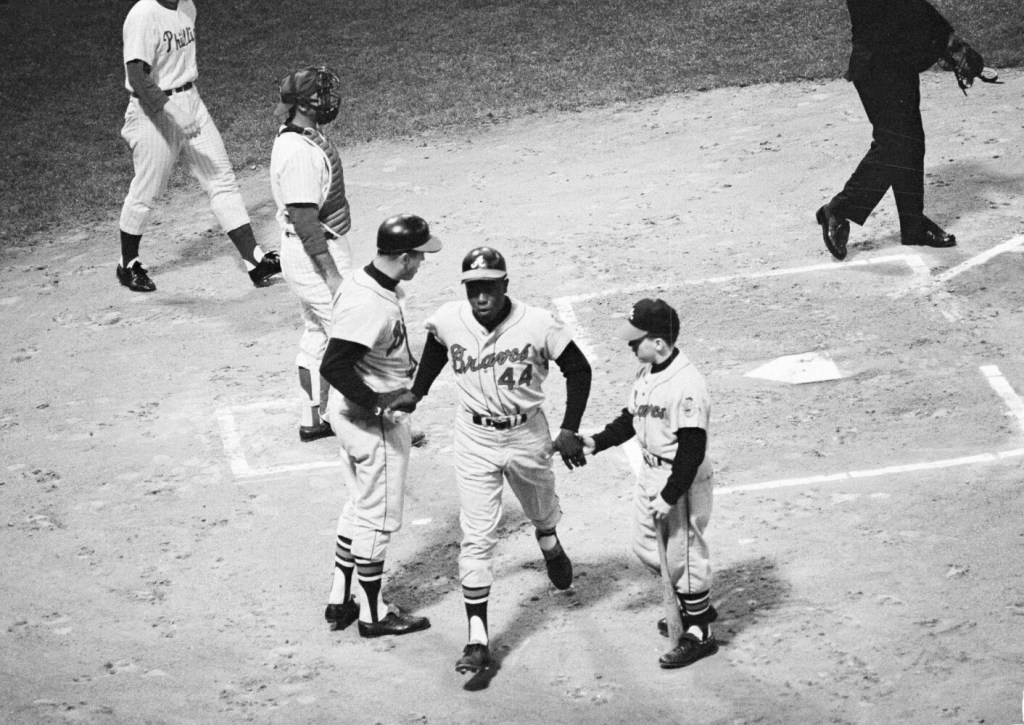

After drawing a walk and scoring a run in the second inning, Aaron came to bat in the bottom of the fourth inning with no outs and a runner on first. The Braves trailed, 3-1.

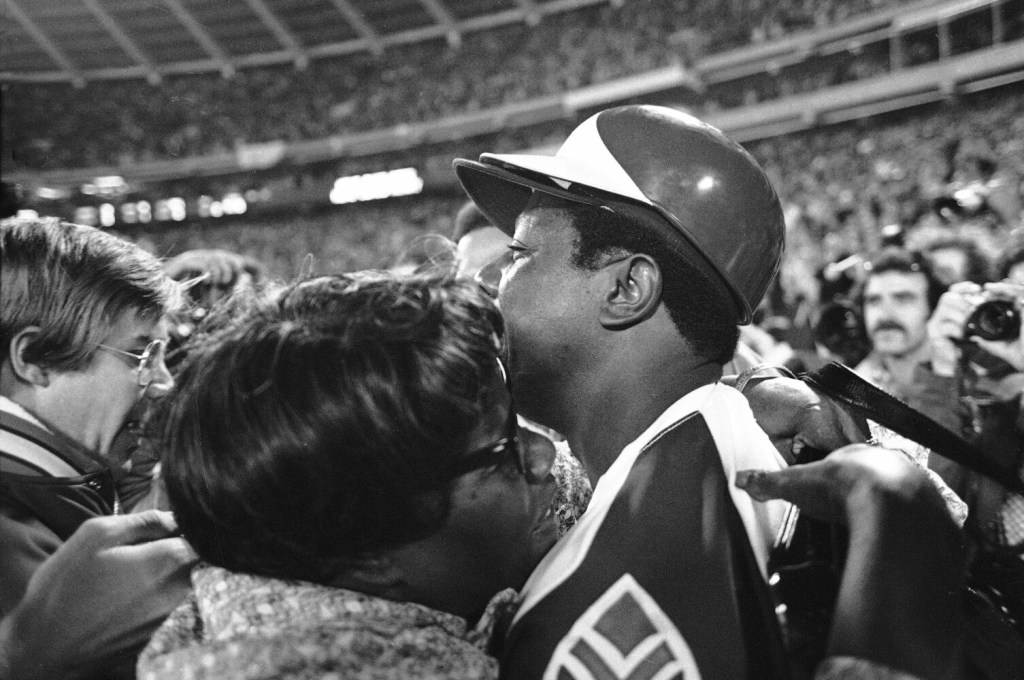

The Dodgers’ pitcher was left-hander Al Downing, who wore the same uniform number as Aaron, 44. On a 1-0 count, Downing threw a slider that caught too much of the plate, and Aaron unloaded a blast that carried over the head of Dodgers left fielder Bill Buckner and into the Braves’ bullpen, where it was caught by relief pitcher Tom House.

Fireworks exploded overhead as Aaron circled the bases, joined halfway through by a pair of college students who hopped the fence. Braves radio announcer Milo Hamilton made the famous call: “It’s gone! It’s 715! There’s a new home run champion of all time and it’s Henry Aaron!”

In the visiting radio booth, Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully put the home run in context: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron.”

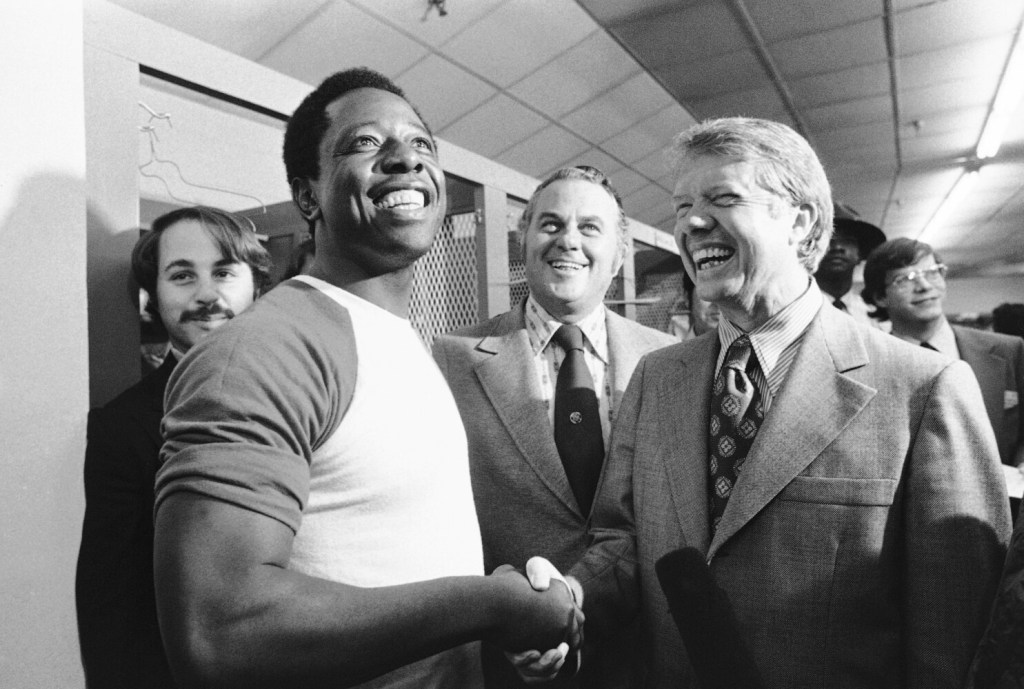

Among those who congratulated Aaron in a ceremony on the field after the home run was Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, the future president. Kuhn, the baseball commissioner, was not present. Aaron never forgot the slight.

• • •

Henry Louis Aaron was born in Mobile on Feb. 5, 1934, the third of eight children. His father was a laborer on the city’s docks.

As a child, Aaron sharpened his hitting by swinging at bottle caps with a broomstick. For years he batted “cross-handed,” with his left hand above his right on the bat, before correcting his hand position.

By 15, he was attending school sporadically but playing baseball regularly on semiprofessional teams. He was primarily an infielder until shortly before his major league debut in Milwaukee in 1954.

He had an uneasy relationship with some of the Braves’ veteran players, including pitchers Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette, and kept largely to himself off the field. But Aaron’s extraordinary hitting helped make the Braves one of the strongest teams in the National League in the 1950s.

In 1957, he led the National League with 44 home runs and 132 RBI and was named the league’s most valuable player for the only time in his career. The Braves went on to win the World Series over the New York Yankees in seven games.

The two teams met again in 1958, with the Yankees capturing the title in seven games. Aaron played 18 more seasons without reaching the World Series again.

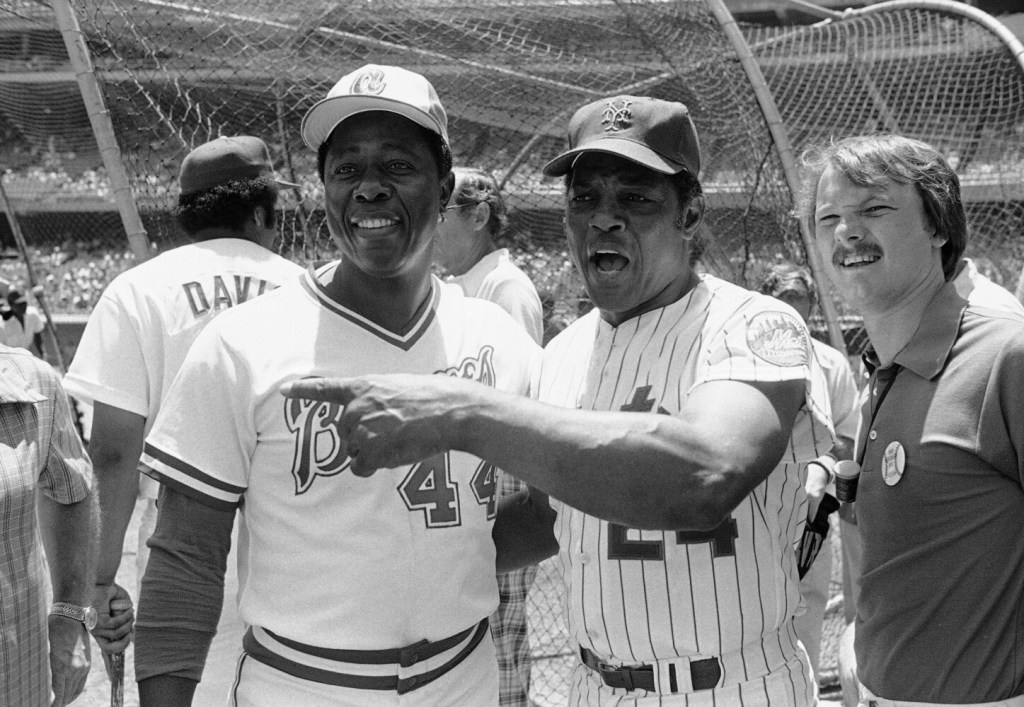

Throughout his career, Aaron was often compared with Mays, his fellow Alabamian. Mays, who spent his career in New York and San Francisco, may have reached more spectacular heights during his career, and his outgoing “say-hey” flair tended to overshadow Aaron’s more understated style of play. But by the time Aaron retired in 1976, he had bettered Mays in home runs, RBI, batting average and runs scored.

At one time or another, Aaron led the National League in virtually every hitting category. He won two batting titles, including a career best of .355 in 1959; he led the league in home runs and runs batted in four times each; runs scored, three times; slugging percentage, four times.

In addition to his 755 home runs, Aaron was baseball’s career leader in RBI (2,297), total bases (6,856) and extra-base hits (1,477). His 3,771 hits are the third most in history, after Pete Rose and Ty Cobb, and he was named to the all-star team every year between 1955 and 1975.

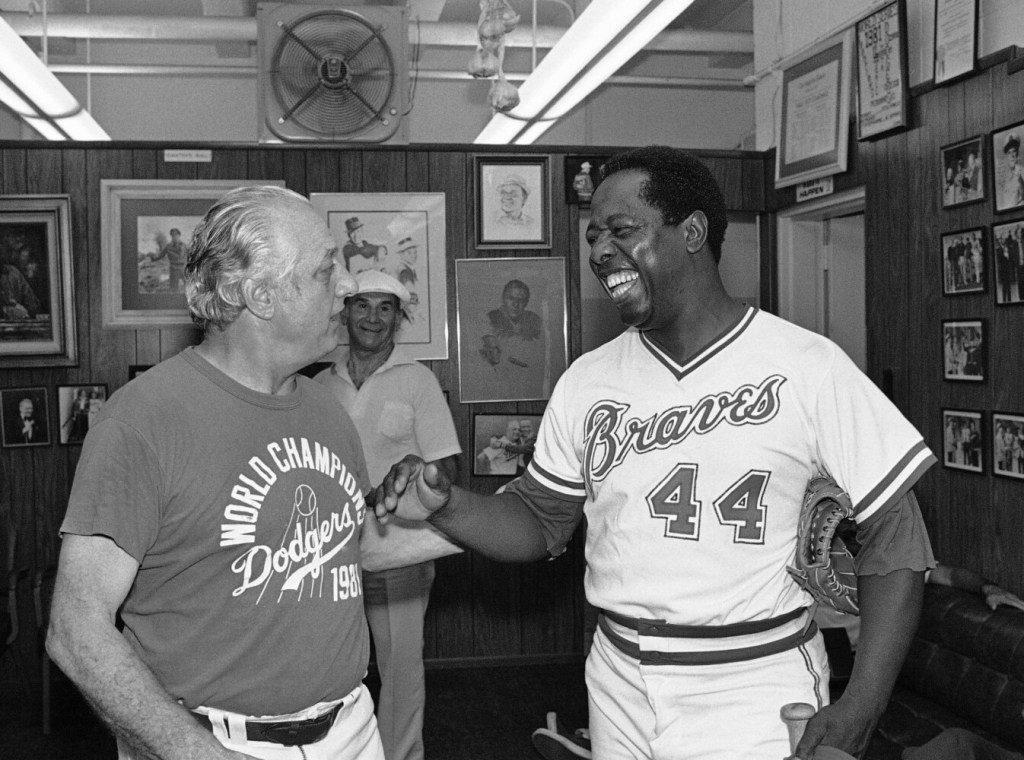

Aaron’s No. 44 uniform was retired by the Braves and by the Milwaukee Brewers, where he played his final two seasons before retiring in 1976. In 1999, baseball introduced an award named in his honor, given to the top offensive player in each league.

His first marriage, to Barbara Lucas, ended in divorce. In 1973, he married Billye Williams. Besides his wife, survivors include four children from his first marriage; a stepdaughter, whom he adopted; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

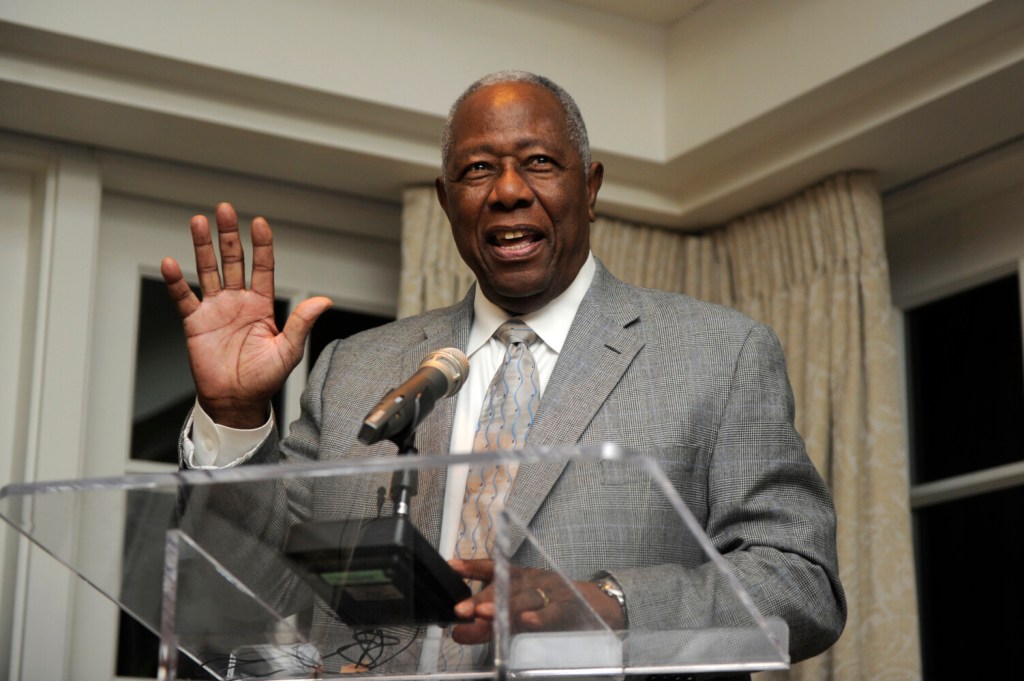

Three decades after he retired, the spotlight found Aaron again when Bonds, the San Francisco slugger, was approaching his record of 755 home runs. When Bonds hit his 756th homer against the Washington Nationals’ Mike Bacsik on Aug. 7, 2007, a congratulatory video message from Aaron was played on the scoreboard in San Francisco.

Privately, according to Bryant’s biography, Aaron “was personally and permanently offended by Barry Bonds” and his widely rumored use of performance-enhancing drugs.

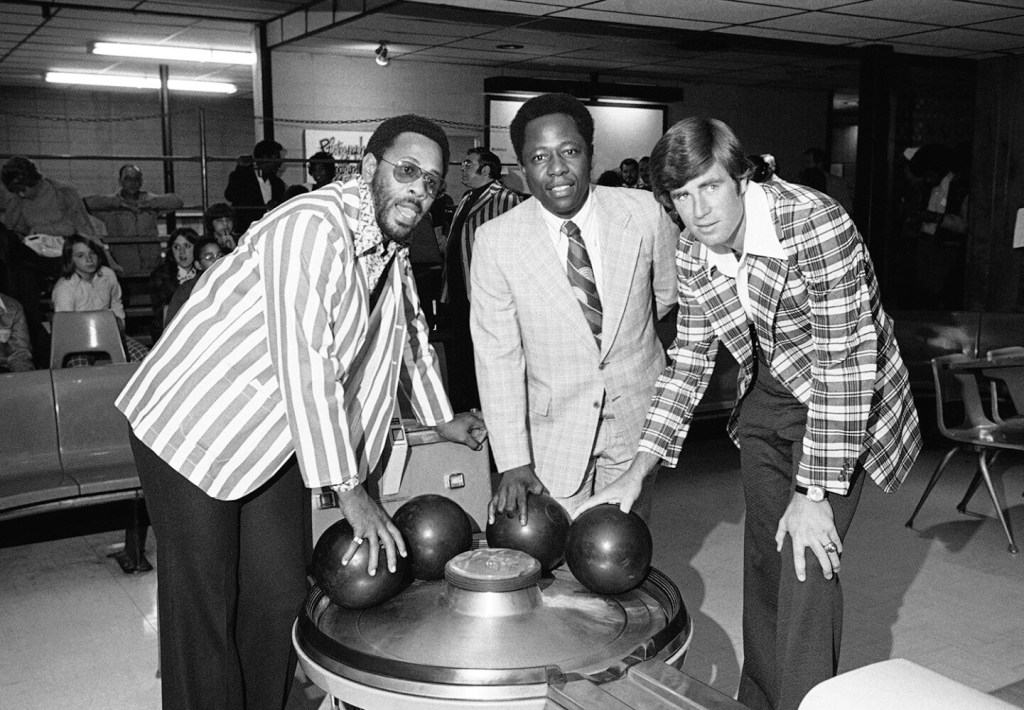

Until then, Aaron had kept a low profile as one of baseball’s elder statesmen. He held front-office jobs with the Braves and had various business interests, including auto dealerships and restaurants. He also maintained a stealthy, behind-the-scenes connection to politics and civil rights. Bill Clinton said that he carried Georgia in the 1992 presidential campaign in part because of an Atlanta rally that Aaron helped organize. In 2001, Clinton presented Aaron with the Presidential Citizens Medal for “exemplary service to the nation.”

Aaron understood that his long march to 755 home runs, leading from Alabama to Wisconsin to Georgia, had a resonance with the civil rights leaders he admired so much. It was about more than gaining respect on the baseball field; it was about earning respect as a man.

“I believed, and still do, that there was a reason why I was chosen to break the record,” he wrote in “I Had a Hammer.” “I feel it’s my task to carry on where Jackie Robinson left off, and I only know one way to go about it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.