On the day that Riverton Trolley Park opened to the public 125 years ago, 10,000 eager visitors boarded trolley cars for the 20-cent round trip to a slice of paradise on the banks of the Presumpscot River.

Visitors enjoyed extravagant performances in a natural amphitheater, a fancy casino building, canoeing, fishing, and vast open green space. The park, built by the Portland Railroad Co., quickly became Maine’s premier destination.

Today, though, with an average of only 9,000 visitors per year, the 19-acre park is considered the most underutilized in all of Portland. But that may soon change.

The city of Portland, in coordination with the Portland Parks Conservancy, a nonprofit committed to supporting the city’s parks, has started a nearly $500,000 project to rehabilitate Riverton Trolley Park.

The proposal, based on hundreds of survey responses from nearby residents, includes what would be Portland’s first mountain bike flow-trail, a renovated entrance and parking lot, eye-catching signage that provides clear directions and explains the park’s rich history, repairs to the Little League field, a picnic lawn alongside a brand new covered pavilion – also the first of its kind in Portland – and re-created portions of a once bustling natural amphitheater.

“The park is really an outstanding place with such a cool history,” said Nan Cumming, executive director of the Portland Parks Conservancy. “Most people didn’t even know the park was there, so people are really excited about this project.”

Public officials and park advocates believe that if the park is utilized to its full potential, it can become a major resource for the neighborhood of Riverton, one of Portland’s most low-income, racially diverse, and fastest-growing areas. In Riverton, 18 percent of residents are of sub-Saharan African ancestry and 20 percent of households received food stamps.

Though Portland ranks well in terms of its public parks, Riverton, according to the Trust for Public Land, holds the largest portion of residents without easy access to nature.

Throughout the U.S., underserved, racially diverse communities are far more likely to be nature-deprived. According to “The Nature Gap,” a report by American Progress, 74 percent of non-white people live in areas of nature deprivation, compared to only 23 percent of white, non-Hispanic or Latino, people.

Inequity in public parks is commonly due to the varying financial abilities of “Friends of” groups, with more affluent communities able to fund larger improvements for their local parks. This has left other parks in more underserved communities behind.

“One of the reasons I decided to run for City Council was the idea that we were the only district without a major park,” said Mark Dion, the District 5 council member. “And I think COVID really reminded us about the importance of outdoor experiential learning as essential not only to the education of the kids, but their mental health and well-being.”

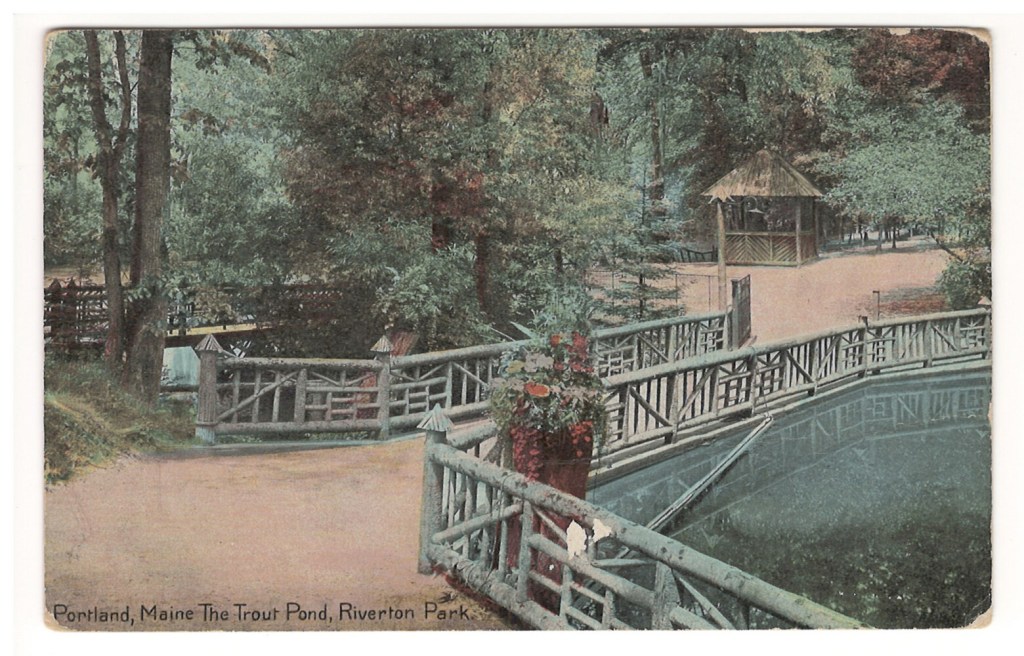

An old postcard of an afternoon performance at the Rustic Theater at the Riverton Trolley Park. Photo courtesy of Portland Parks Conservancy

In late May, the city of Portland applied for a $250,000 Land and Water Conservation Fund – or LWCF – grant to help complete the Riverton Trolley Park project. The city and the Portland Parks Conservancy plan to split the other almost quarter-million dollars needed for the project.

Though many residents expressed interest in redeveloping features of the old trolley park, significant developments are prohibited on the protected land. The Portland Parks Conservancy also found that most people wanted the park to be left in its natural state.

“There’s something to be said for maintaining aspects of a community instead of just bulldozing it away,” said Curt Barnes, a resident of Westbrook. “There’s really a need for places like this where people can go and get a sense of serenity, something that can eliminate the turmoil that seems to be overwhelming our world.”

Regardless of how well the park is rehabilitated, the issue of accessibility remains one of the largest barriers for nearby communities to reap the benefits of the park. More than one-third of the 373 survey respondents, conducted as part of a public planning campaign funded by the Maine Community Foundation, listed improved pedestrian access as their No. 1 priority for the park.

As a part of this project, the city is looking at ways to increase accessibility – for example, a crosswalk across Riverside Street into the main entrance of the park with a flashing beacon.

The city estimates that once the entire project is completed, in an estimated one to two years depending on the success of the LWCF grant, the number of annual visitors will exceed 36,000 – four times the amount the park is seeing now. Portland’s first mountain bike flow-trail will play a big role in attracting those from around the area to the park.

“We don’t have a mountain bike facility in Portland, and especially for families with lower incomes, they can’t be driving their kids out to those spots every day,” said Cumming. “So we really need something that’s locally accessible.”

Another main feature of the renovations will be attractive new signage, in multiple languages, discussing the history of the land going all the way back to the Presumpscot River as Wabanaki fishing grounds.

Signs will also provide clearer directions and detail the fascinating history of the trolley park, a turning point in the history of Maine’s tourism, which had long been geared toward upper-class citizens.

“The electric rail car really made tourism more equitable,” said Jamie Rice, director of collections and research at the Maine Historical Society. “And today with the rise of electric vehicles, it’s really great to see that this has a place and a presence in Maine’s history.”

In 1921, with the rise of the automobile and World War I having drastically changed life in America, the railroad company decided to sell the park so it could become an automobile amusement park. Just over a decade later, during the heart of the Great Depression, the park shut down for good.

The city of Portland later acquired the land to be made into a public park. For decades, it has remained tucked away as a rare, hidden gem of Portland.

“I’ve lived in Portland my whole life, 37 years, and I’ve never been here before,” said Nico Coolbrith on his first walk in Riverton Trolley Park. “When I saw the water here I was almost reduced to tears because it was so beautiful.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.