In 2016, Quartz, an economic analysis organization composed of journalists, surveyed 20 museums in seven countries to determine how much of the work of 13 major artists was on display and how much of it sat in storage. Among their findings? “Taken together, only 44 percent of the art included in the survey was on display. That’s 689 works in storage for just the dozen artists we surveyed.”

This is not just an issue for museums like the Metropolitan in New York or the Tate in London. Works in storage are low-hanging fruit in a way, so it’s surprising that more museums don’t tap this readily available resource. Colby College Museum of Art is doing just that by periodically reaching into its archives to assemble thematic exhibitions that highlight some of their rarely seen works. That was the impetus for “The Poetics of Atmosphere: Lorna Simpson’s ‘Cloudscape’ and Other Works from the Collection” (through April 17).

As the title indicates, the focal point of the show is a video by Lorna Simpson called “Cloudscape,” around which assistant curator of modern and contemporary art Siera Hyte organized a small group of works by both well-known artists, such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Alexander Calder, and less bold-faced names, such as Sally Egbert and Arnold Bittleman. The unifying theme is how our bodies experience, interact with and affect the atmosphere around us.

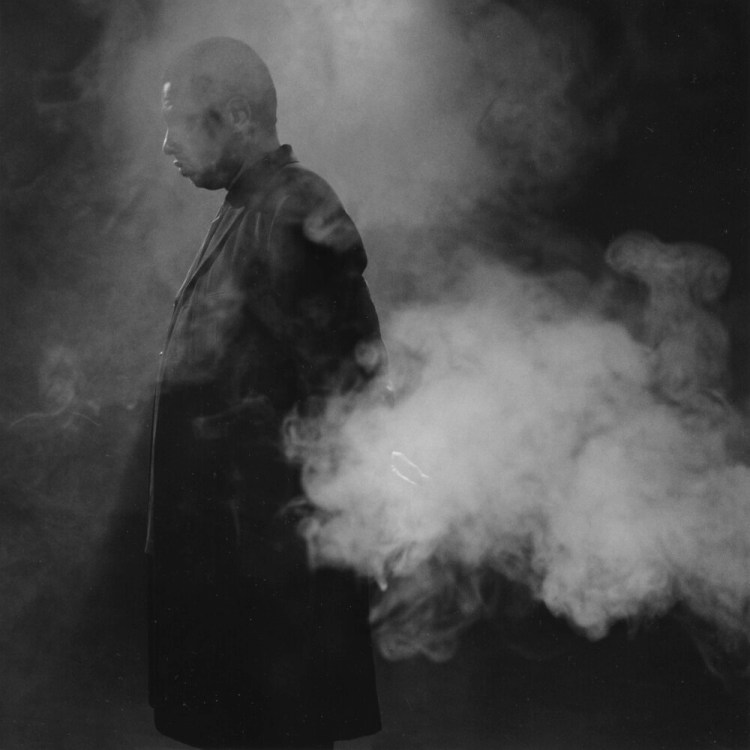

In Simpson’s video, the late award-winning multimedia artist Terry Adkins stands in the middle of an empty room, whistling an odd tune as fog slowly fills the space, eventually engulfing him in invisibility. Then the fog thins and disappears as gradually as it came, leaving Adkins calmly whistling his tune. This cycle repeats itself one more time before the video ends.

For me, the work elicited memories of reading Ralph Ellison’s novel “Invisible Man” and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “Between the World and Me.” Both these books speak about the effects racism’s toxic environment on Black bodies.

Coates searingly writes: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage. Enslavement was not merely the antiseptic borrowing of our labour – it is not so easy to get a human being to commit their body against its own elemental interest. And so enslavement must be casual wrath and random manglings, the gashing of heads and brains blown out over the river as the body seeks to escape. It must be rape so regular as to be industrial.”

The tune Adkins whistles is an obscure African American spiritual, chosen intentionally by Simpson and Adkins to be vaguely familiar, yet unfamiliar as well. The video transmits a feeling of quiet, immovable defiance. No matter how the fog attempts to erase Adkins’s identity and physical presence, it cannot. We hear the whistling through the mist even if we cannot see him. And the bodily act of whistling seems to blow the fog out of the room.

The late critic Okwui Enwezor wrote of “Cloudscape” that it “appears to be a song of departure from the charnel house of the racial sublime. But,” he cautioned, “this does not mean it will disappear completely, since race and masculinity still have social meaning.” Yet we end as we began – with Adkins standing imperturbable and very physically present despite an atmosphere that has tried to obliterate him.

This is by far the most powerful work in the exhibition. None of the others appear to have a political or social context. One possible exception is Julie Mehretu’s print, “The Residual.” Mehretu sees her abstract mark-making as “characters that hold identity and have social agency.” Fundamentally, many of her works are maps of human civilization’s progress through the landscape, tracing their histories, their societies, wars and their effects on the world they’ve touched.

Julie Mehretu, “The Residual,” 2007. Color sugar lift and spit bite aquatints with hard ground etching, and drypoint. 40 3/4 in. x 50 1/4 in. (103.51 cm x 127.64 cm). Museum purchase from the Lindsay Leard Coolidge ’78 Print Acquisition Fund, 2010.033

In “Residual,” the ramifications of human presence on the landscape seem to have left it degraded and in disarray. The obsessively worked surface looks like an aerial view of mountains and crevasses beset by whirling, almost violent winds and energy currents. It is a magnificent piece, whether it intends this message or not.

Many works focus on artists’ preoccupation with the sky and clouds. This is exemplified through Arnold Bittleman’s “Untitled (Cloud Study),” which accurately and beautifully portrays a cloud’s sense of emergent billowing. Vincent Andrew Hartgen’s “Neptune Churn” loosely alludes to dark storm clouds over waves crashing against the rocks. And Arthur Wesley Dow’s “The Big Sky (or Marshes),” a woodblock print, is all clouds and sky, but for a sliver of land at the bottom.

Cao Xiaoyang, “The Twenty-Four Solar Terms: Vernal Equinox,” 2019. Charcoal on paper, 60 1/4 x 40 9/16 in. (153 x 103 cm). The Lunder Collection, 2020.004

The most ethereal of these is a large drawing by Cao Xiaoyang. By using charcoal rather than brush and ink, Xiaoyang is challenging our view of traditional Chinese ink brush landscapes. It is a sumptuous, otherworldly image worthy of long contemplation. Besides telegraphing the quiet serenity of traditional Chinese landscapes, it is astonishing to see how the artist has captured the sense of moisture-laden mists and their slow, vaporous movement using what is essentially a dry medium.

Others invoke atmosphere more obliquely. Sally Egbert’s “Perfumes” uses translucent liquid washes of paint, a jewel-like palette and elements of collage to convey something we normally smell but do not see. This work recalls Helen Frankenthaler’s stain paintings and the fluid biomorphic forms of William Baziotes. It effectively conveys a sense of a scent’s atomized cloud, the different elements suggesting the perfume’s complex mixture of notes – floral lavender, perhaps, mixed with hints of citrus (orange) and streaks of spice (red cinnamon, black pepper and so on). Or there is Charles Birchfield’s “Lakeview,” which feels like a humid summer day.

Charles E. Burchfield, “Lakeview,” 1915. Watercolor, 8 5/8 in. x 11 11/16 in. (21.91 cm x 29.69 cm). Bequest of Adelaide Moise, 1986.042

Some choices feel a bit puzzling. Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “Christ Walking on the Waters” may connect to “Cloudscape” in terms of its religious reference (here a Bible story and, in Simpson’s video, the spiritual Adkins whistles). But it feels more like a traditional religious depiction than much having to do with atmospherics. Georgia O’Keefe’s painting of a feather laid over a shell is lovely, but also appears more like a still life than saying anything in particular about atmosphere. And Etel Adnan’s minimalist piece, Hyte told me, feels “almost hot” to her. Perhaps. But I would argue Birchfield’s “Lakeview” feels hotter. It also doesn’t seem, at least to me, to be one of this artist’s stronger pieces. The orange sphere at its center certainly could be a sun, but the dull color surrounding it mutes that heat in some way.

But these are minor quibbles. I am happy to see work normally in storage, especially those by artists I had never heard of (in particular Egbert and Bittleman). You could say, among the show’s other pleasures, that Hyte has created an atmosphere of discovery.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.