James Robinson used to tell people he had a lazy eye, even though he’s always known that’s not true.

He learned as a youngster it was the simplest way to address the questions from classmates or the uncomfortable sideways glances from adults when they noticed his eyes were looking in two different directions. It was certainly easier than trying to explain the actual medical terms associated with his condition: strabismus, alternating exotropia and a complication called anomalous retinal correspondence.

Robinson went on to study documentary filmmaking in college, and for his senior project, he decided to tackle the dilemma of explaining what he sees and how he wants to be seen. Prompted by questions from his family, he made a film. He used creative animation and on-film experiments to give some idea of what he sees – two images at the same time, one in each eye, jumping and moving from side to side. As narrator, he tells the audience he calls his eyes “whale eyes” because when people look at whales – creatures that have an eye on each side of their head – they are not at all bothered by the fact that they can only see one of them at a time. “That’s the kind of acceptance that I’ve always craved,” he says in the film.

Robinson’s documentary about his condition was picked up by New York Times Opinion Video and debuted online in July 2021. The newspaper then offered Robinson, 26, of Portland, the chance to make more films about little-known or hard-to-explain medical issues. That three-film series, called “Adapt-Ability,” debuted on the New York Times website Aug. 16. It featured films dealing with stuttering, progressive blindness and face blindness.

While the New York Times does not disclose the number of views its videos receive, the series gained praise and emotional comments from readers around the country as well as calls for more films from Robinson, said Adam Ellick, director and executive producer of Opinion Video at the New York Times. Robinson’s “whale eyes” film has gotten more than 557,000 views on YouTube.

Ellick said he was especially impressed by Robinson’s inventive ways of conducting experiments on screen that help make his point. In the stuttering film, Robinson displays a mechanical device he calls a “listenometer” with three levers – one for removing each major kind of stutter. Then, through precise audio editing, he lets the audience hear what it would sound like if the film’s subject – New York-based writer John Hendrickson – did not stutter.

“James has a strong and accessible voice. He writes his video scripts with a unique perspective. He is not just an observer, but also a participant in this topic,” said Ellick. “He then invents super creative visual techniques that transcend his words. I like to think of the visuals as active experiments that allow the audience to experience his commentary. That is a transformative use of the digital video medium.”

Robinson, who has been working as a freelance filmmaker since graduating from college two years ago, chose the topics and found the subjects to interview for “Adapt-Ability.” He said he really wanted the series to be more about how able-bodied people can connect with and adapt to people with disabilities than the other way around.

“The series flips the script of the archetypal disability profile,” said Robinson, who graduated from Duke University in North Carolina in 2020. “Rather than profiling how disabled individuals have overcome their conditions, I focused on how an abled audience can overcome their discomfort with disability.”

Robinson’s next big project in the coming year will be to write a middle grade nonfiction book for Penguin Random House called “Whale Eyes,” based on his film and his personal experience. The book is due out in 2024. He says he will also do more film work in the coming year, possibly including some for the New York Times, but has not finalized any projects yet.

Robinson said he’s been heartened by the response from his “Adapt-Ability” films, including from doctors who are sharing them with patients, teachers who are showing them in class and people with the condition, grateful that someone took the time to explain what they go through.

“It is 10 a.m. on a Tuesday in late August and tears are streaming down my face … I have stuttered since I was a young child, and I will stutter my whole life,” wrote one commenter from San Francisco. “This is an extraordinarily well-produced piece of filmmaking that captures so much of what I wish I could easily share with others about stuttering.”

EXPERIENCE THE WORLD

Robinson was born with strabismus – a misalignment of the eyes. While some newborns outgrow it, Robinson did not. He had two surgeries to try and correct his vision by the time he was 18 months old, but neither worked. Robinson’s specific type of strabismus is known as alternating exotropia, where one eye at a time looks outward. He’s also got a complication called anomalous retinal correspondence. Together these conditions don’t allow the images seen in each eye to be combined in his brain, the way they are for most people. The result is that Robinson has virtually no depth perception, everything looks two-dimensional. Each eye sees something individually but his brain doesn’t combine the information from each eye. So images appear to be jumping in front of him, as the image moves from eye to eye.

Since he’s always seen this way, Robinson has adapted over time. He says watching shadows can help him judge where an object is, for instance.

In the “whale eyes” film, he talks about not being able to hit a ball off a tee in Little League, when everyone else could. He says he “bumps into things” from time to time. Sometimes when people hand him something, it takes more than one try for him to grab it. He says he buys pre-cut cheese so he doesn’t have to deal with sharp knives. He was able to get a license but does not drive much.

Robinson grew up in several places, including Hingham, Massachusetts, and the suburbs of Chicago, and mostly attended mainstream schools. His father works as an energy consultant, and his mother has taught architecture and engineering. But the family has roots in Maine going back several generations, and they spent family vacations in the Down East town of Cutler. The family moved to Portland permanently after Robinson graduated from high school, and that’s where he’s living now.

Paul Kram and a cutout of Oprah Winfrey’s face in a scene from James Robinson’s film on face blindness. Image courtesy of The New York Times, Opinion Video

For most of his childhood, he didn’t watch TV, his parents deciding it was better for Robinson and his two brothers to experience the world for themselves, rather than through the lens of children’s TV shows and TV advertising.

“We lived in the woods (in Massachusetts) so they could really go out and explore for themselves,” said his mother, Laura Robinson. “We didn’t want TV having power over them.”

He was given exercises to do that might help him adapt to the way he sees things, his mother said, including throwing and catching a baseball. He also played a lot of tennis, partially because the rackets are fairly big and forgiving, at least more forgiving then a baseball bat. His family learned to be patient and adapted as well, even if they couldn’t fully understand what he was dealing with.

“Within the family, you get used to the dropped things. If you hand him a piece of paper, he might miss. But you just hand it to him again,” his mother said.

Robinson did watch some TV, with his parents or in school, and he was immediately drawn to documentaries. He remembers seeing some films from Ken Burns but especially liked the in-depth investigative pieces on the PBS series “Frontline.” At around the age of 12, he began “playing around” with his parents video recorder. One of the first projects he undertook on his own involved interviewing refugees living in the Chicago area about their experiences.

His mother remembers being surprised at how naturally her son seemed to be at the skills of putting together a film, including finding the right music and being able to tell a “very compelling story.” By the time he was in high school, he was serious about pursuing film as a career. He applied to Duke specifically because he wanted to study at the college’s Center for Documentary Studies.

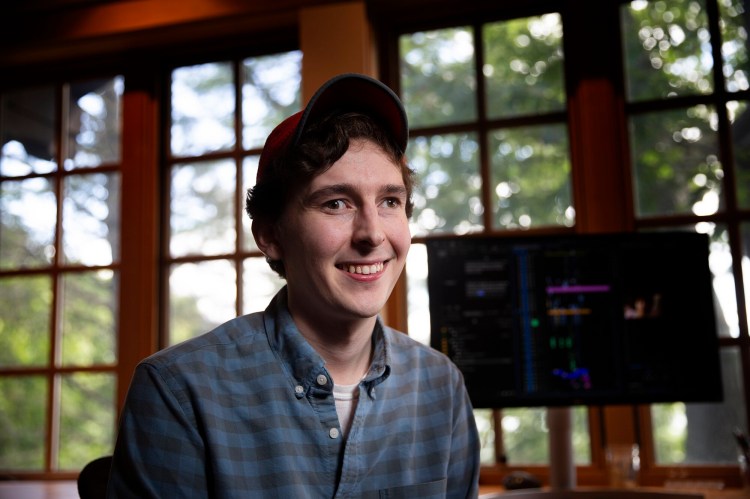

James Robinson, a filmmaker from Portland, has done a series of New York Times Opinion videos on various disabilities, including one on his own rare eye conditions. Derek Davis/Staff Photographer

WHAT DO YOU SEE?

Robinson said his family had been asking him to demonstrate – using his film skills – how he sees. So he decided to try to answer the question for his senior film project at Duke, and that film became

“How Life Looks Through My ‘Whale Eyes.'”

The film is a very personal exploration of how Robinson sees and wants to be seen. He’s shown having casual conversations with his mother, father and two brothers. At one point, he asks his younger brother Reed to explain what’s wrong with his eyes. His brother’s answer was “you’ve got a lazy eye.”

His demonstrations of what his vision is like includes asking each family member if “the red dot is inside or outside the box.” But on screen, his family are only seeing the outline of a box. Then he askes the same question, and each family member only sees the red dot. “I don’t see a box,” one of his brothers answers.

“Is this what’s like for you?” his mother says. “Oh, God.”

Robinson narrates the film himself. He’s soft-spoken, conversational and even-keeled. He’s seen wearing shorts, a sweatshirt and a baseball cap. He mixes on-screen experiments and tales of his childhood and development with creative graphics and animation. He shows himself swimming below the ocean’s surface while “everyone I meet is frolicking happily on the the ship they’ve dubbed the U.S.S. Normal.”

After graduating in the middle of the pandemic, Robinson took a job working remotely for a while for a Los Angeles-based documentary company. While pitching story ideas and trying to get freelance jobs, his “whale eyes” film – which was about 24 minutes long – was recommended to Ellick at New York Times Opinion. Ellick said New York Times Opinion Video is a platform for filmmakers and YouTubers to showcase their work, and he is always looking for new contributors who can offer different perspectives on social issues or events. He said he realized the film’s potential to reach people and wanted to present it on the New York Times site. The final version was about 12 minutes long.

“The essay was a gripping personal odyssey about James’s struggle to adapt to a society, and even to his own family, that wasn’t always comfortable with his disability,” said Ellick. “I was struck by both the personal story, but also the mesmerizing visual storytelling. The larger idea, of course, speaks to the millions of Americans with other disabilities who find this journey relatable. ”

The film got such a “glowing” response that New York Times Opinion Video officials decided to offer Robinson the chance to make the “Adapt-Ability” films, following the theme of explaining various disabilities in Robinson’s unique style and voice.

Robinson worked much of the past year on each of the three films, each about eight minutes long. He searched long for one person with the condition to focus on in each film. For the film on retinitis pigmentosa – progressive vision loss – he found Yvonne Shortt, a New York-based artist. For the film on prosopagnosia – face blindness – he focused on Paul Kram, a retired software engineer from Vermont.

In both those films Robinson shows that there’s no one size fits all explanation for these conditions. A lot of people think of blindness as “flipping a switch” that shuts off sight, said Robinson. But his film with Shortt shows that a person can lose small portions of vision over a period of time that may allow them to do some things, like painting or writing, but have trouble walking without a cane. At one point in the film, Robinson uses a straw to illustrate some of what Shortt sees.

In Kram’s case, he can see people’s faces but his brain doesn’t process that he’s seen a certain face before and knows who that is. In the film Robinson, shows Kram a cut out of Oprah Winfrey’s face – just her face, no hair, no neck, no parts of her body – and he cannot guess who she is. When Robinson reveal’s it’s Winfrey, Kram says “of course” he knows who Oprah Winfrey is but couldn’t place her name with just her face.

The stuttering film begins with Hendrickson on the phone, trying to answer an automated voice asking “how can I help you” or whether he wants to speak to someone in the pharmacy. Each time the voice moves on to a different prompt before Hendrickson can answer.

Robinson, as the narrator, explains that Hendrickson is one of the 20 percent or so of people who stutter into adulthood and that there’s no real cure. Using his invented “listenometer” – which looks like an old adding machine – he presses levers marked “repetitions,” “prolongations” and “blocks” to remove certain kinds of stutters from Hendrickson’s speech. When he presses all three, Hendrickson speaks without stuttering, thanks to very precise editing.

Hendrickson said during his life he’s wondered if his stuttering might keep him from finding a partner, from getting married, from reciting his vows.

“Everyone expects you to have beat it by now, because adults know how to talk,” he said.

Later in the film, Robinson tells the viewers that the “listenometer” only shaved 65 seconds from Hendrickson’s dialogue during the film. He says that while we all might have to wait a few extra seconds for a person who stutters to get their thoughts out, “John and those who stutter have been waiting much longer for us to listen.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.