The Baron

by Scott Sell

Maine’s Dick Curless rose from Aroostook County roots to become the state’s most successful country music singer

I saw Dick Curless before I’d ever heard him. I was digging through crates at a used record store in Boston, looking for rare gems to add to my collection, when he appeared in the stacks—gazing into the horizon, his face framed in the side mirror of a tractor-trailer, a black eyepatch over his right eye. With tracks like “Big Wheel Cannonball” and “Truck Stop,” I knew, without even listening to it, that these were songs for the road. The album was Hard, Hard Traveling Man and I bought it immediately.

Nicknamed “The Baron of Country Music” after one of his songs, Curless specialized in “truck driver’s music,” telling stories about and for long-haulers, as well as those who appreciated good yarns about life on the road. At the time he was writing and playing these types of songs, mostly in the 1960s and early 1970s, the highway network in the United States was growing larger and interstate truck drivers, as a result, were putting in long hours behind the wheel. It was a new and exciting career, but also a lonely and backbreaking one. Curless’s songs became their soundtrack.

“It was the way he put all his feelings out there,” said noted music historian, Peter Guralnick, the author of biographies about Elvis Presley, Robert Johnson, and Sam Phillips of Sun Records fame. “It was the tenderness of his voice, the soulful intimacy with which he transformed every song into a moving personal statement. People felt that.”

Born in 1932, in Fort Fairfield, prime potato country in Aroostook County, Richard Curless was raised on healthy doses of Jimmie Rodgers records and Gene Autry films. He also came from a musical family—his mother played the organ and his father sang and played the guitar. When he was eight years old, he and his family left Maine for Central Massachusetts, where he began playing music of his own. At seventeen, he caught the attention of Massachusetts cowboy vocalist Yodeling Slim Clark, who began mentoring Curless and gave him the guitar slot in his radio band, The Trail Riders. It was soon evident how versatile Curless was: He could excel at barnyard stompers, barroom weepers, and novelty songs, like “Jelly Doughnuts,” in equal measure.

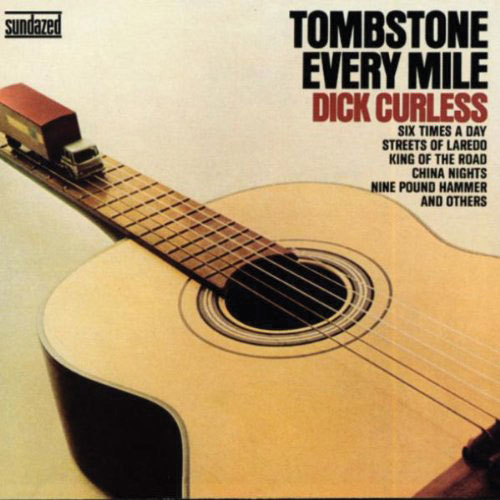

A Tombstone Every Mile

While enjoying tour recognition and regional airplay, and recording singles for New York City’s Standard label, Curless married his wife, Pauline, and settled down in Bangor. But it wasn’t long before the Korean War reared its head and, despite a bad heart and a serious eye problem—hence the eyepatch—Curless was drafted in 1952. He drove an Army truck, giving him plenty of inspiration for future songs. He also worked at the Armed Forces Korea Network as a disc jockey and on-air performer known as the “Rice Paddy Ranger.” His career ebbed and flowed after he returned home two years later. Even though he had graduated from doing one-night stands at Maine bars to making television appearances, his music wasn’t yet a household name. And worse: His health conditions, combined with the stress of being an increasingly popular musician, would sideline him for months at a time.

But then, in 1965, his moment arrived. With the help of famed copywriter Dan Fulkerson, Curless landed his biggest hit: “A Tombstone Every Mile.” Starting with the sound of a winter wind blowing, the song tells of dangerous winter driving up on Highway 2A through the Haynesville Woods in northern Maine, “a stretch of road, up north in Maine/That’s never ever ever seen a smile/If they buried all the truckers lost in them woods/There’d be a tombstone every mile.”

With its loping rhythm section, ace storytelling, and Curless’s signature baritone, it hit a nerve with the nation’s truck drivers and country-and-western lovers. The song played on every truck stop jukebox and catapulted up the charts, peaking at No. 5 and staying in the Country Top Ten for the better part of that year. The hit launched a career that would make him one of Maine’s most popular musicians and undoubtedly its greatest country performer.

Top 40 Hits

After “Tombstone,” he recorded nineteen more albums and during the most productive period of his career in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he scored twelve Top 40 Billboard hits, including “Six Times a Day (The Trains Came Down)” and “Big Wheel Cannonball.” His last Top 100 hit came in 1973 and his penultimate U.S. album was recorded in 1974. He was inducted into the Maine Country Music Hall of Fame on April 30, 1978, and got the DECMA Country Music Pioneer Award in 1982. And then he faded from radio airplay. He had moved to Branson, Missouri, and seldom toured or released an album, slowly retiring from the music business. But luckily, there would be a final magical burst of musical inspiration some twenty years later.

Dick Curless’s final album is considered one of his finest. On the verge of fading into obscurity by the mid-nineties, Curless teamed up with Peter Guralnick’s son Jake, a producer for Rounder Records, a label whose musicians have now won more than forty Grammy Awards.

According to Jake Guralnick, Maine native and blues musician Michael “Mudcat” Ward, who had worked with Jake to record a Sleepy LaBeef album, suggested several times that they record Dick Curless, but all Jake really knew about Curless was that “he was known for his incredible truck driving record, ‘Tombstone Every Mile,’ and that he wore an eyepatch. Both were unimpeachably cool credentials.”

Soon, the project received a green light at Rounder.

“I went to the three Rounder owners, and asked them if I could record Dick Curless,” Jake later wrote about recording the album. “To their eternal credit, there are certain records that Rounder made that never had a chance of turning a profit, but that seemed like they were important to do for historical posterity. This was one.”

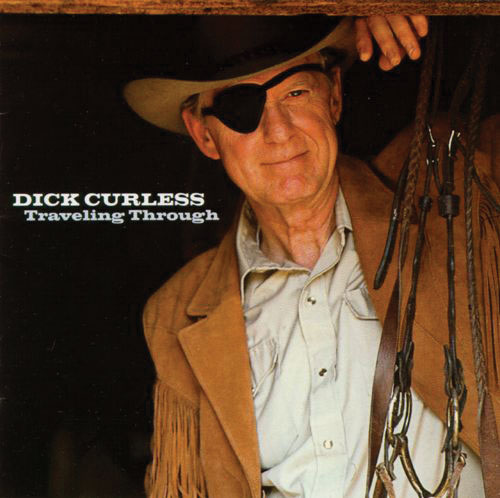

Traveling Through

Recorded on a slim budget at Longview Farm in Brookfield, Massachusetts, the sessions found Curless in top musical form. The arrangements were stripped-down, putting his distinctive voice front and center, a slide guitar often adding the high and lonesome sound to complement his baritone. And although elements of his truck driver song days were present, the songs drew on the more introspective and spiritual side of country music. Though it never spawned a hit single, no less an authority than Sam Phillips called it a great album.

“I’ve never been present at a more ambitious, more inspiring session,” the elder Guralnick said. “I just wasn’t prepared for the emotional impact, the improbable combination of transcendent musicality and homespun truth that took place in the studio. Sometimes the intensity, the sheer beauty of the way Dick sang a song stopped the musicians in their tracks.”

Curless, who was so sick he had to take breaks while recording, died from stomach cancer just a few months after the session. He had been in the hospital while the album was being mixed, and because everyone involved had such a deep attachment to the project, no one seemed able to come up with a suitable album title.

“We just couldn’t think of anything that would do justice to its scope, its grandeur, its human vulnerability,” Peter Guralnick said. “A few days before he died, Dick named it himself with a phrase from his beautiful version of Merle Travis’s ‘I Am a Pilgrim’ that could be taken, I suppose, as both its message and his sense of his own life’s journey. He wanted it to be called Traveling Through.”

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2018 edition of Islandport Magazine.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2018 edition of Islandport Magazine.Islandport Magazine is published quarterly by Islandport Press a family-owned, Maine-based publishing company dedicating to producing books and other media that capture and explore the grit, heart, beauty, and infectious spirit of Maine and New England. Click here to subscribe to Islandport Magazine.