‘The 2013 Portland Museum of Art Biennial: Piece Work” is a gorgeous show. The work is strong and the curatorial theme is compelling.

I particularly like that “Piece Work” illustrates my oft-repeated (maybe too-oft) opinion that the most important critical trend in Maine contemporary art is concept-driven work relying heavily on process and craftsmanship.

However, we have some business before we sit down to the meal.

First, if you are a painter or a painting fan, then stop reading this now because there’s nothing more here for you.

There is one painting in the show, but it is sequestered in the McClellan House and wasn’t even painted in this decade. (Typically, biennials limit themselves to recent works, so this stings doubly.)

You could argue that Duane Paluska’s works are paintings, since they hang on the wall and often have paint on them. But they are shaped pieces of wood largely covered in sail canvas that maintains its original color, so they are closer to collage or assemblage. Moreover, Paluska is a sculptor and this work sets your brain into 3D mode – like when you see room lines at diagonal angles but your brain explains to you they are flat lines seen in perspective. This might be my favorite work in the biennial; but it’s not painting to me.

The biennial’s call for entries said “work in any medium will be considered” when it should have said “painters need not apply.”

Of the 870 rejected artists, I bet about half of them were painters. After all, painting has always been the driving force behind Maine’s art economy and reputation.

The other bit of business is that the PMA sent letters to a “handful” of artists requesting they apply to the biennial. That is not only completely unfair to the rejected artists, but it rubs up against the ethics of a “juried” show.

The 2013 biennial is not a juried show: Part invitation, part open call – it’s a curated show. That shift might be acceptable to the terms of the bequest by Maine artist William Thon and his wife that created the PMA biennial (I don’t know), but it should have been announced before the call for entries went out – not after. Standards are fundamentally important, but, unfortunately we don’t have sufficient space here to discuss practices like outside jurors, etc.

It’s extraordinarily frustrating to have this “business” interrupting what could otherwise be an enthusiastic discussion about the juror, Jessica May, the museum’s newish curator of contemporary and modern art, and scads of excellent art – but in a March interview with Bob Keyes, May said, “We’re going to own this biennial and take responsibility for it fully, from soup to nuts.”

I blame the chefs: too many nuts. Now, on to the soup.

The first course is Adrienne Herman’s and Brian Reeves’ wallpaper installation of Post-It note lists. While you immediately notice the repeating scale as defined by the magenta “SHRED” notes, it’s a witty affirmation of Herman’s brainy but vernacular touch.

The main presence in the first gallery is Lauren Fensterstock’s 10-by-10-by-4-foot solid black landscape based on English farm boundary trenches. The thousands of hand-cut black paper elements are obsessively impressive and gorgeously punctuated by a reflective black Lucite stream at its bottom.

Next are Jocelyn Lee’s series of photos of “Kara.” They are so disturbingly creepy that I don’t mind that we’ve seen them several times before.

Drawing is very strong in the biennial. Kate Beck’s 100 graphite/paper/panel works form an elegant grid anchoring the center gallery.

Alison Hildreth’s five 80-by-36 inch topographical/archeological map drawings on paper reveal she has expanded her language into motion and 3D whimsy.

Joe Kievett’s three fabric design-like large drawings are extraordinary monuments to detail (think OCD) – one has about 1.3 million distinct (and precise) marks in a grid.

JT Bullitt’s drawings remind me of Jeff Woodbury’s indexical, data-based drawings; Bullitt’s “I Will Not Stop Until I am Asleep” comprises a single black ink line that meanders back and forth with 3D topo-like echoes until, presumably, the artist actually fell asleep.

Bullitt’s two-hour recording of his reading the names of everyone he recalls ever meeting is a hilariously absurd work within an art world so polarized about name-dropping.

There are several very strong thread/fiber works true to the theme of “piece work” including Crystal Cawley’s “Vague Idea Vestment” with its handsomely (and mysteriously) couched puzzle pieces and Allison Cook Brown’s “Glove #3” – white organza evening gloves with double snap expanders under which Brown embroidered shocking blood red.

Other particularly notable works include Carrie Scanga’s “Echolocation,” a soaring dark-but-moonlit sky monotype standing over a bronze ferry sculpture swirling in a mound of monotyped paper forms, and Abbie Read’s “Library,” a cabinet-of-curiosities book wall that looks like a Joseph Cornell/Louise Nevelson collaboration.

Finally, for dessert, we visit the McClellan House: Jason Rogenes’ lighted Styrofoam works carry on the Nevelson logic beautifully and wittily.

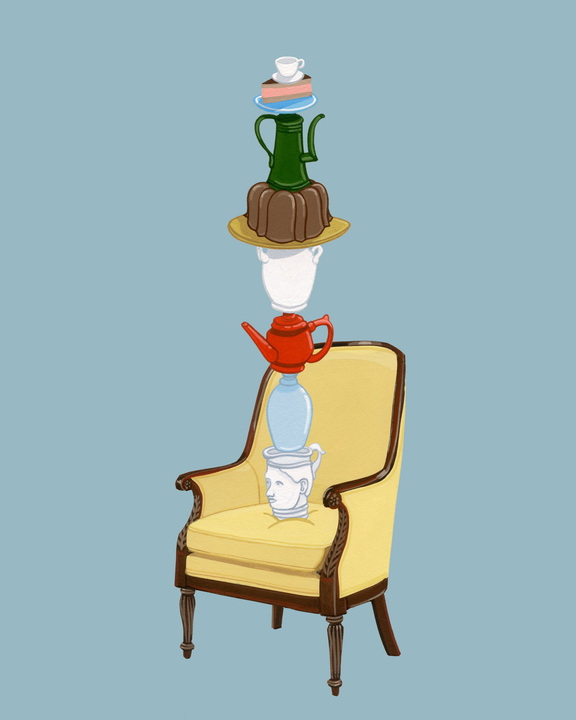

Justin Richel’s Kohler residency has paid off – his slip cast “Endless Column” (think Brancusi) of cakes, plates and cups is a towering presence at the 1801 mansion’s front entrance.

Zach Poff + N.B. Aldrich’s “Sferics 2: Bell Cloud” features a grid of bells on the ceiling (think “Downton Abbey”) that ring when a low-frequency receiver picks up atmospheric disturbances even hundreds of miles away.

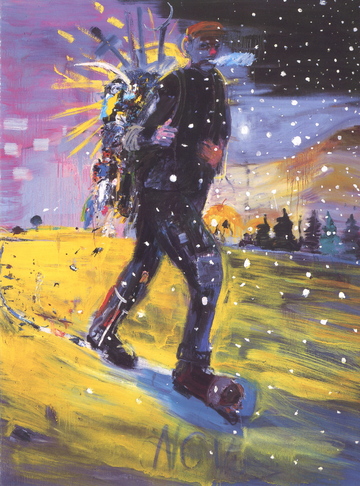

Matt Blackwell’s two works are virtual layer cakes of symbols – and one is actually a painting.

While it’s too bad this process-focused show interrupts itself with questions about its own process, this is the most elegant PMA biennial to date and I think it’s a harbinger of great things to come from the PMA’s first curator of contemporary art.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.