How much conscious control does an artist have over the content of his work? This is an important question about any artist or work of art.

Artists, especially blossoming professionals, inevitably overstate their control of their work’s content. (The public, however, must share the blame for this, because we pressure artists to speak with authority about their work.)

It’s a sign of maturity when artists don’t pretend viewers can only see the results of the artist’s intentions.

It makes sense that truly great artists such as Picasso and Matisse tend to say very little about their content. We want them to think visually. We don’t, after all, look at paintings to be lectured, but to flex our visual intelligence and aesthetic sensibilities.

However, when I challenged myself with the “conscious control” question about “Reflections Within Form,” David Driskell’s current show at Greenhut Galleries in Portland, I might as well have breached the Hoover Dam from down in front.

Driskell is not only an extraordinary painter, but a person of incomparable experience, erudition and depth about whom we should ask: Is he one of America’s greatest living artists?

Driskell is the subject of books, films and national exhibitions. He is an author and historian as well as an historical figure in his own right for reasons such as being the first black artist to have a solo show at South Africa’s National Gallery.

Driskell has had a home in Falmouth since the 1950s. He fell in love with Maine when he first studied at Skowhegan in 1953, and Maine has been a huge component of his art and life ever since.

Driskell’s paintings of pines in the 1950s revealed his extraordinary talent, and he still paints Maine pines. There are pines in this show from 2010, ’11 and ’12, and from 1961.

His paintings are bold, colorful, dense and loose. They tend towards simple subjects: Trees, a figure, a mask or angels in a forest. But in terms of content, they are deep, rich and complex.

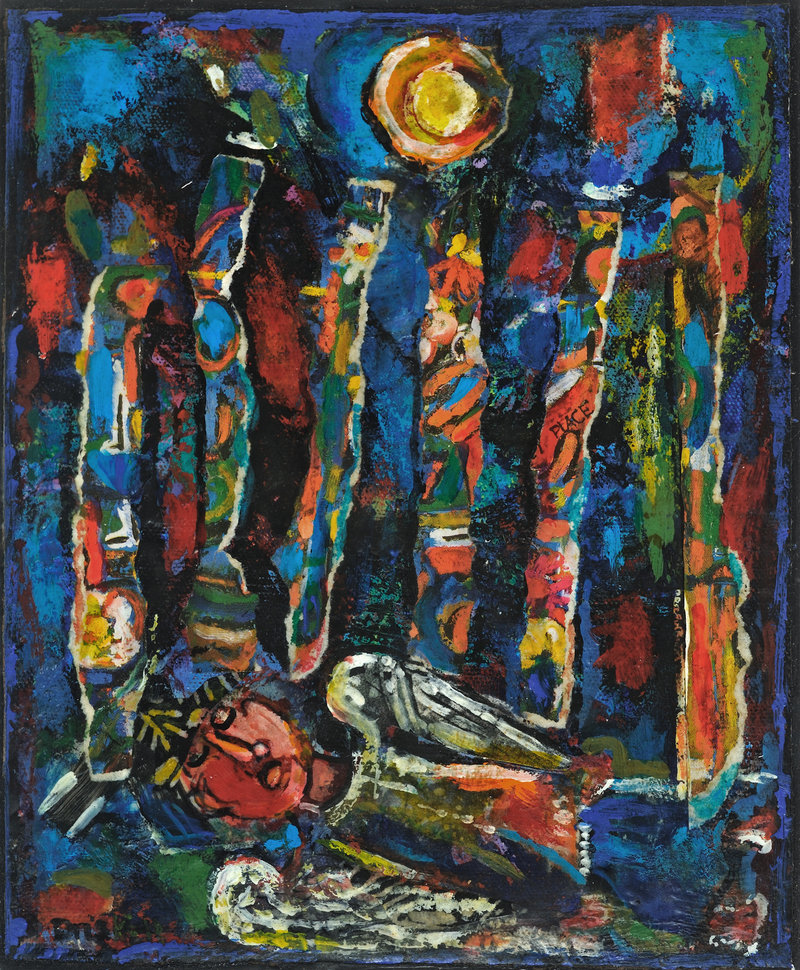

“Dreamer in the Forest,” for example, features an African mask floating in a dense jungle-like forest. Stylistically, it reaches out to African art, but more towards Matisse, American quilting and, importantly, the great Cuban artist of Chinese and African decent Wilfredo Lam (1902-82).

Lam’s mixed heritage draws Driskell’s mixed cultural identities into the conversation (American, black, Southern roots, Mainer, artist, etc). Driskell — who has authored books on the African diaspora — finds his footing and voice as an American artist.

To wit: American slaves were not allowed to have masks, so ironically, they enter Driskell’s paintings as they entered Picasso’s, Modigliani’s and the German Expressionists, despite how they reflect on Driskell the man.

Ultimately, Driskell’s melting pot logic and blending of religions makes the point that America is a culture of diaspora. We have all been displaced to be here, even the indigenous peoples.

This digs extraordinarily deep as cultural commentary, because ultimately, Driskell is a Christian artist. His work doesn’t just refer to the fact that our Western culture’s entire history of painting was Christian for centuries; it participates in that history with genuine spiritual affect.

The model for Driskell, therefore, is the French painter Georges Rouault (1871-1958), whose Christian religiosity inspired his paintings.

The black stained-glass-like lines and saturated colors of Rouault are apparent in Driskell’s work, though less apparent is his religiosity. But it’s there. Rouault’s France was a Catholic nation, while Driskell is a black man in America, so the connection is less obvious.

But make no mistake, “Adam and Eve, Bamboo Forest” is un-ironically biblical despite its direct quotations of Matisse (who decorated chapels, let’s not forget).

The strongest works in the show are Driskell’s two angel paintings and his “Old Mexican Church,” a turquoise, Mondrian-inspired masterwork that is the most luscious monochrome I have ever seen.

“Sleeping Angel” directly recalls Henri Rousseau’s great “Sleeping Gypsy” at MoMA, and reminds us that Maine has been America’s leading home for Lebanese Christians of Bedouin ancestry. So I see this as a work about African Christianity because of Driskell’s Maine roots.

I find the clarity of Driskell’s faith to be warmly welcoming. It allows his work to occupy a culturally moral ground rather than the individualized experiential spirituality of Abstract Expressionism or nature-inspired landscape painting.

The spirits in Driskell’s work — such as in the 1986 study for his great “Spirits Watching” — do not exude pagan power; instead, they appear as ancestors — angels, apostles and otherwise.

The question stands: Is Driskell one of America’s greatest artists?

I suggest you see “Reflections Within Form” and answer that for yourself.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.