“Tinderbox,” now on view at the Maine College of Art’s newly reshuffled Institute of Contemporary Art and curated by Visiting Assistant Professor for Jewelry & Metalsmithing Kyle Patnaude, ostensibly “merges brutally insightful visual art, contextual information nodes for public engagement, as well as an ‘art punk’ concert.”

The exhibition incorporates some excellent work by several extremely sharp artists, so it offers a fine experience for the already-inculcated contemporary art audience. But the messaging of “Tinderbox” is more blunted than blunt, and its point is frustratingly vague. It has the sense of being watered down by the discourses surrounding the show – as if the ideas it wants convey are in orbit around the objects rather than the other way around.

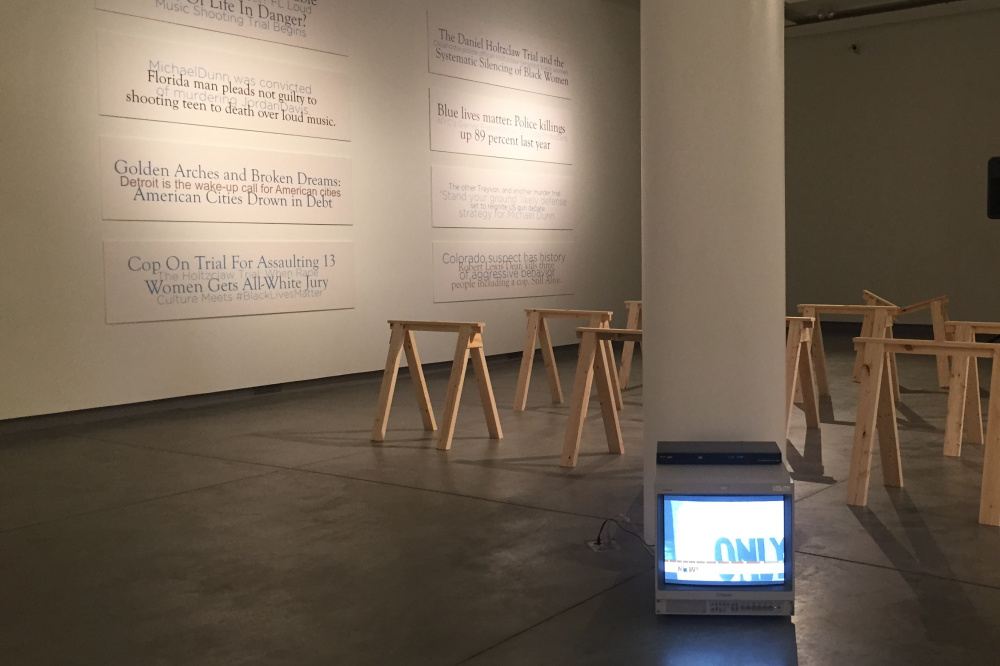

“Tinderbox” features five artists: Tyanna Buie, Martine Kaczynski, Adam Manley, Trina May Smith and Hi Tiger – a Portland-based art punk musical performance ensemble comprising Derek Jackson, James Paul and Ness Smith-Savedoff. Buie’s stylized print, drawing and collage-oriented paintings feature faceless, forgotten figures that reach back to a fractured childhood in which identity feels fragmented. Kasczynski’s input consists of a small group of handmade, blank A-frame sandwich signboards that convey a sense of fleeting announcements, not unlike, perhaps, a site-specific conversation about Twitter rather than tweets. Manley’s contribution is a conceptually sizzling phalanx of 24 freshly assembled wooden sawhorses that will be treated to a back-breaking thumbscrew-like machine one by one at regular intervals during the run of the show. Smith’s paintings feature cleanly painted scenes of suburban-ish blight: groups, details or single houses from economically stressed cities like St. Louis or Milwaukee that are in various states of being abandoned, dilapidated or, even, on fire. Hi Tiger’s work featured a live opening-night performance, but visitors to the exhibition can still see several mixed media sculptures. Work not associated with any specific artist in the “public aggregate space” includes two series of text-oriented wall panels and a circled group of three video-looping televisions on the floor that provide the clearest sense of topic for “Tinderbox”: racial tension in America.

While the “public aggregate space” contribution is the only work that establishes a clear line on the subject, even it is largely clear of over-determined ideology. And while this is an admirable quality, it doesn’t speak loudly enough to do the curatorial job of weaving the rest of the work into a coherent fabric. For a segment of America, however, the mere assertion that racial tension is a topic of national priority smacks of ideological dogma (i.e., the folks who subscribe to the Talk Radio meme that anyone who is concerned with race is a “racist”). The wall text work, however, presents often-conflicting tweets and headlines together in such a way that anyone should be able to find their own opinions or news sources represented. The effect of this approach offers what should be a moderate mirror – yet isn’t because of the effective (and very real) conservative media meme that because prioritizing racial issues is itself “racist,” any conversation about the topic is “racist” and therefore should be verboten. “Tinderbox” fails to ignite because it doesn’t effectively identify or address such barriers to a national dialogue. The wall text work identifies some of the potential conversationalists, like Donald Trump, but doesn’t account for the asymmetrical barriers to a national dialogue (i.e. one side refuses to participate). Considering the shape of the show, this is a curatorial mistake – not a failure on the part of the artists.

The primary shortcoming of “Tinderbox” is that it doesn’t critically identify the problem it seeks to address. Hi Tiger’s specific (and more effective) approach sounds like this: The problem is racial conflict and the major barrier is the intentional denial of shared discourse and dialogue. In other words, until the Fox News wing of America can find the courage to stop stonewalling (irony intended) and agree to have a dialogue about our national race problem, it will increasingly fester like an open and infected wound.

To follow the wall texts’ compelling activist discourse straight to the ostensible content of “Tinderbox,” however, is to ignore the actual structure of the exhibition. The “public aggregate space” works are the last the viewer encounters. Kaczynski’s blank signs are first, followed by Smith’s paintings – and they could be about poverty (Maine, after all, is neither short on landscape painting nor ramshackle houses), the off-shoring of American jobs, the societal blight of crystal-meth or any of a dozen other flavors of low-hanging fruit. It is strong enough painting that it doesn’t easily play the role of someone else’s illustration.

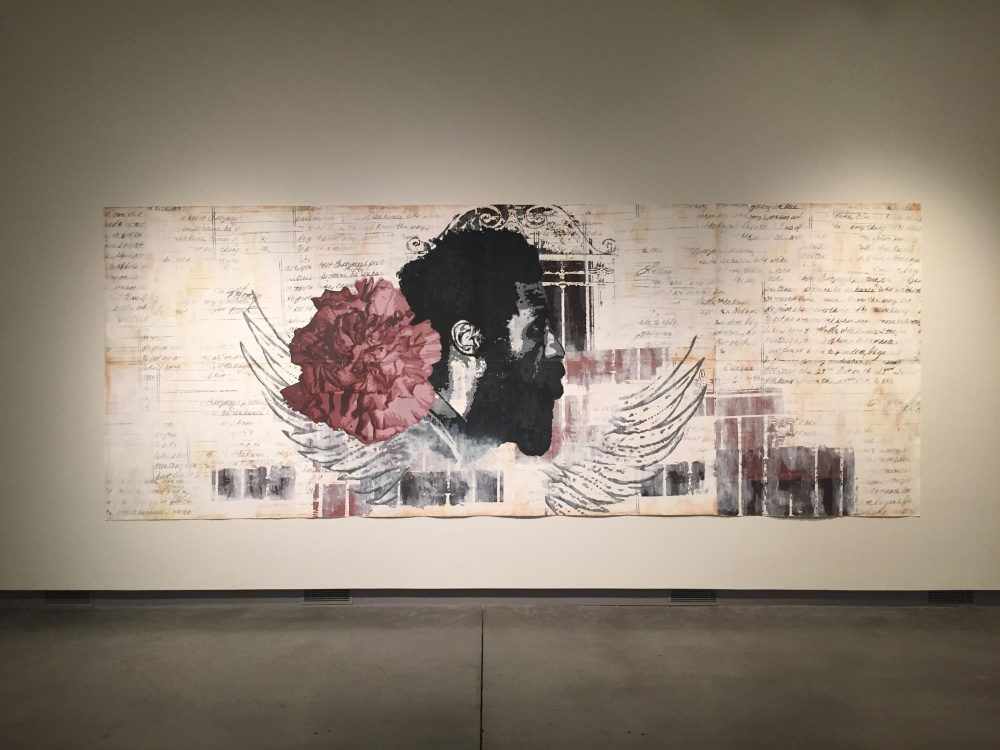

On its own, Buie’s large “Sweet Escape” is a strong painting. It features a sort of personal logo (a semi-pixelated and tat-like bearded man’s face in profile abreast of wings that repeats in other works) set as the figure over a field of (slightly too) beautifully handwritten self-referential texts. (A closer reading might reveal more, but little intrigued me other than two differing ways of referring to the writer’s mother, which implies two different – foster? – mothers.) Buie’s work is rich enough that it would stand better on its own, but it is frustrating in this context because knitting it into the narrative of the exhibition relies on too much prior knowledge and too many assumptions. (And assumptions make for very uncomfortable spaces when pressed up against Hi Tiger, Smith and Manley.)

The problem with “Tinderbox” is that it feels like an art school project dedicated more to internal conversations about the show’s thematics than to the public experience of an art exhibition. MECA’s primary responsibility is the education of its students, after all, but if part of the ICA’s mission is to introduce MECA students to effective curating, then even from an internal perspective this is a very flawed show.

My concern with the past two ICA exhibitions is that they have largely failed to engage the public. It is particularly disappointing in this case because I feel very strongly about the intended messaging of the exhibition, specifically the idea that we need a constructive national dialogue about race conflict in America. If such an idea is floated within an inaccessibly abstruse contemporary art exhibition, it might actually turn away or desensitize an otherwise potentially sympathetic audience. Clearly, the last thing curator Patnaude would want is to further disenfranchise his socially engaged contemporary artists, but, no matter how much I hope it’s not true, that may be the cumulative effect of “Tinderbox.” Unless you are merely preaching to the choir, it’s not enough to announce your ideological position to your audience: You need to be persuasive.

While the curatorial theme of “Tinderbox” constitutes a potentially damaging failure, it nonetheless comprises some worthy and compelling art that will appeal to an experienced and sophisticated contemporary art audience and other members of the choir.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.