Twenty-four-year-old Lauren Leonard of Peru got in serious trouble with the law over crimes directly related to her use of heroin. She’s six months sober now, but says she wants to leave western Maine, which is rife with opioid use. “I don’t have enough clean time to be around people using,” she says, “I know that.”

Third of 10 parts.

PERU — Last April, as her addiction was spiraling out of control, Lauren Leonard was stopped by drug enforcement agents in Auburn with 20 grams of heroin in her car.

Like many addicts, she had become a low-level dealer as a way to have access to the drugs she craved so badly.

Police charged her with felony drug trafficking, an offense punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

Nearly a year later, Leonard, 24, has been in recovery for more than six months and is trying to turn her life around. But she faces a significant jail sentence for the drug offense, and her future is uncertain.

Is Leonard a criminal who deserves to be punished? Or is she a sick person, grappling with a chronic brain disease, who needs compassion and treatment?

Such questions reflect a fundamental divide in how society responds to the drug crisis – a divide between those who see addiction as the consequence of bad behavior and those who see it as a disease or disorder that takes over the brain.

The divide is important because it affects public policy.

When addiction is viewed by lawmakers as bad behavior, the response is to increase drug enforcement efforts. That was the thinking behind the nearly 50-year war on drugs, a largely failed effort that packed jails with drug users and mostly low-level dealers but did little or nothing to reduce the addiction problem.

Interviews with dozens of family members of overdose victims and of people in active recovery revealed that criminal charges were a major barrier to treatment and to long-term recovery. Jails offer little or no treatment and, in most cases, if someone is on probation and fails a drug test, they will go back to jail, even though relapses are a common part of recovery.

But criminalizing addiction takes focus away from harm reduction efforts. Policymakers who see addiction as bad behavior are less likely to support increased use of naloxone, which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, or to fund needle exchanges or even safe injection sites – all of which are proven to both save lives and steer people toward treatment. Maine Gov. Paul LePage is among those who has been outspoken against these types of efforts.

When addiction is treated as a disease, the response also tends to be more humane and more medically driven. A review of government efforts in several communities and states shows that a compassionate approach has yielded success. Launched in 2015, the Gloucester, Massachusetts, Police Department’s “angel” initiative, which effectively offers amnesty to drug users in exchange for enrollment in treatment programs, became a model for cities and towns across the country.

States that have made noticeable investments in medication-assisted treatment such as methadone and Suboxone or in more in-patient treatment beds, as Vermont has done, have been successful in slowing the rate of deaths.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy last November released a report on addiction, the first of its kind. He said he hoped it would do for addiction what previous surgeon general reports had done for smoking in the 1960s and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s: force the public to pay attention. One of his main points was that society has a big role to play in fighting the crisis.

“But you can’t legislate or mandate culture change,” Murthy said in an interview with the Press Herald. “It has to come from people and the language that they use.”

Leonard still struggles with that. She still has trouble thinking of her addiction as a disease, but she said talking about it helps fight the stigma because she takes back some control.

“I think people are so quick to apply this label of addict,” she said. “People are so much more than that. I’m more than that.”

‘THE CAPACITY TO TAKE CONTROL’

Peter Leighton, a primary care doctor in Bridgton, said the 90 or so patients he sees with substance use disorder don’t fit neatly into one category but there are similarities. He said people who view addiction as a choice or a moral failing are looking at it wrong.

He doesn’t see addiction as any different from someone who develops Type 2 diabetes or heart disease.

“In almost every case, people with diabetes or high blood pressure have made choices that led to those conditions – what they ate or whether they exercised,” he said. “But we don’t make the same judgments about them when they seek treatment. Why should addiction be different?”

Stephen Barbour had tried detox in 2013 and again in 2015. He also tried managing his heroin addiction with Suboxone but without success. Late last spring, the Westbrook native ended up at Operation Hope, a program offered by Scarborough police.

In less than 24 hours, Barbour was on an Amtrak train headed to a residential treatment facility in Massachusetts. The staff there treated him like a patient with a disease, but in some ways, that scared Barbour. The idea of having to live with this for the next several years, having to manage his sobriety, weighed on him.

Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

Just as people with addiction struggle with seeing it as a disease, so too do people who have studied the topic extensively.

Gene Heyman, a professor of psychology and addiction at both Boston College and Harvard University, has written extensively about addiction and argues that addiction is voluntary and driven by choices.

FROM THE EDITOR

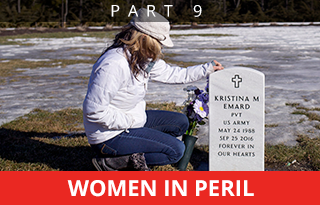

COMING WEDNESDAY: The children left behind: As one generation dies, the next one’s in peril

“Most addicts keep using until the penalties of excessive use become overwhelming. The signs are the staggering monetary costs addiction exacts on society and the tragic personal costs for those closest to drug users, particularly children,” he wrote in a 2014 New York Times piece. “What research shows is that those we label addicts have the capacity to take control of their lives.”

Heyman is right, but people often need help, like resources and a support system. Those aren’t there for many.

Another professor of psychiatry who has studied addiction – Carl Hart at Columbia University – rejects the premise that addiction is a disease. In a recently published article in Nature, Hart said the collective push to call addiction a disease was driven to help engender empathy in a way that would promote better public policy.

“We are nowhere near being able to distinguish the brains of addicted persons from those of non-addicted individuals,” he wrote. “Despite this, the ‘diseased brain’ perspective has outsize influence on research funding and direction, as well as on how drug use and addiction are viewed in society.”

At some point, though, the language is semantic. The collective response to the drug crisis has still fallen short in almost every metric, particularly the most important one: the number of people dying.

A woman covers her head in an intake cell at Cumberland County Jail. She was arrested on drug related warrants and was found with a crack pipe and codeine, an opiate used to treat pain.

OPIOIDS’ EFFECTS ON ‘RATIONAL THINKING’

Those who see addiction as a disease point out that opioids change the functioning of the brain and body.

As many as 50 percent of people with a substance abuse problem have a severe, chronic disorder that’s managed only through intensive treatment and continuing aftercare, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

If left untreated over time, addiction becomes more severe, disabling and life-threatening.

Leonard, who has learned through counseling that her upbringing, her relationship with her mother and her genetics all contributed to her addiction, was barreling down that path.

The period between when she started using and when she realized things were out of control was blurry – and remarkably short.

“At first, it would be my reward after a (lousy) day at work,” she said. “Then that turned into: waking up in the morning feeling like (crap). That turned into: It was the only thing on my mind. There was no rational thinking with any of it.”

The first wake-up call came in September 2015 when drug agents came to the house she shared with her boyfriend. He was on probation that included regular unannounced check-ins. On that day, there was heroin in the house. Leonard tried to get rid of it by snorting it. Agents saw her, and she was charged with falsifying evidence. She paid a fine, but her boyfriend went to jail.

Lauren Leonard, 24, got hooked on heroin after graduating from high school, and in her hometown of Peru, population 1,541, a lot of people know it.

“At that point, I hated my life,” she said. “I hated my boyfriend. I couldn’t even look at him. I blamed him for all of this.”

The incident put Leonard on police radar. After she was arrested in April 2016, her father left her in jail for three days. From there, she went to treatment at a residential rehab facility, Crossroads in Portland. She stayed for two weeks before her insurance company informed her that it would no longer cover the cost because it wasn’t necessary.

When she came back home to Peru, she entered an intensive outpatient program, which included Suboxone. She’s not on medication-assisted treatment now and like many in recovery has mixed feelings about it, although she does recognize its value.

Leonard’s support system at the moment is her dad, whom she lives with. She also is on his health insurance, at least for a little while longer, which helps pay for any treatment.

“I’m so lucky to have the resources I do,” she said. “There are so many people who don’t.”

Her legal case has given her incentive to stay clean, but that’s not the only thing.

“I just had this realization that I could easily die alone in my bedroom,” she said. “And I don’t want to do that.”

WESTERN MAINE – ‘LIKE A WAR ZONE’

VITAL SIGNS: Cuts to MaineCare made treatment unaffordable for many drug users, and admissions to treatment programs declined. In 2013, the Maine Department of Health and Human Services reported 7,453 admissions, a 25 percent increase over 2011 and a sign of growing demand. But by 2015, after MaineCare cuts went into effect, admissions had declined to 6,372.

Even when patients are treated with compassion and medicine, it doesn’t guarantee success.

From the moment Stephen Barbour checked into rehab last year, he rarely left his room. He was given Suboxone to control his cravings but he felt terrible. He couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t eat. He couldn’t regulate his body temperature. The constant check-ins by staff there drove him crazy.

By the time his third night arrived, Barbour couldn’t do it anymore. He left the facility against medical advice and returned home. He still had some Suboxone stashed away there. He would try to manage it on his own even though he knew he had tried and failed so many times before.

A few weeks after returning home from the treatment facility, Barbour stopped answering his phone or responding to text messages. Notes left on his door also went unanswered.

Treatment experts have come to agree that counseling, sometimes intensive and long-term counseling, coupled with medication-assisted treatment, is the best option but not everybody sticks to it.

Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General, said the 21st Century Cures Act, the largest piece of health care legislation since the Affordable Care Act, is an unprecedented step toward addressing the crisis. Enacted late last year, it includes $1 billion for states to spend, mostly to expand treatment.

Meanwhile, drug agents are arresting more people than ever for trafficking in opioids. Sometimes it’s higher-level dealers, but more often it is people like Leonard, caught between crimes and their addiction.

On Feb. 9, she celebrated six months clean, the longest period since she began using. Her treatment consists of group meetings once a week. She worries whether it’s enough.

She wants to learn a trade and have a career but also worries about what kind of opportunities she’ll have with a felony drug conviction. She’d like to get into a deferred sentencing program, like drug court, but the county where she lives doesn’t offer it.

That means she could likely spend time in jail. Her lawyer has been talking to prosecutors about a plea deal and she is scheduled to be back in court in April.

What she really wants is to get out of western Maine, which is rife with opioid use.

“It’s like a war zone,” she said. “I don’t have enough clean time to be around people using, I know that.”

When she feels a craving, she remembers it’s the disease and that it will pass. She gets in her truck and drives. She turns the music on and tries to think about life six months or a year down the road. Life without opioids.

“I’m just trying to do the next right thing,” she said. “If you put enough good karma out there, eventually you get to watch it come back.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.