GLOUCESTER, Mass. — Once he settled on the unprecedented approach to tackling his community’s drug crisis – a decision spurred by four overdose deaths in the first three months of 2015 and a public forum during which his community screamed out for something different – Police Chief Leonard Campanello gathered his officers to explain the new mandate.

Addicts will no longer be treated as criminals, he told them. They will avoid drug possession charges in exchange for enrollment in treatment. They will be given a chance.

It was a radical shift in policing, but Campanello said his staff fell in line immediately.

“I think if you talk to a police officer for three or four minutes, he’ll tell you what you’re taught, that possession of illegal drugs is a crime and we need to act as law enforcement officers,” the chief said recently. “But if you talk to them for more than five minutes, … then they absolutely know that a different approach – where they can stick to their oath of serving and protecting and also do what most of them came to the job to do, which is help people who are in real need – is warranted.”

In the first three months since Campanello instituted the “Angel” program, 145 people have come into his police department. Every one has been placed in treatment, a broad category that can encompass everything from detox followed by methadone, to more intensive residential therapy.

Although its long-term efficacy is unknown, the Gloucester program has sparked a national conversation about how communities should handle the increasing problem of drug addiction. It’s a radical departure from the traditional approach to the war on drugs that has dominated U.S. policy for decades – but that has done little to reduce drug-related crime or addiction.

Overdose deaths in the U.S. jumped from 3,036 in 2010 to 8,257 in 2013, and the numbers for 2014, when finalized, are likely to be even higher. Also, overdoses have moved out of urban streets and into suburbs and rural areas, making the problem more acute.

Campanello’s approach arrives at a time when law enforcement and government officials across the country are desperately seeking solutions to the growing scourge of drugs, in particular the skyrocketing use of heroin.

The program may soon find its way to communities in Maine, where drug overdose deaths have reached all-time highs, where heroin deaths alone jumped from seven in 2011 to 57 in 2014, where Portland saw 14 overdoses – two of them fatal – within a single 24-hour period in August, and where political and community leaders have come together in recent weeks to declare a crisis and to discuss solutions.

“I really think it’s innovative,” Augusta Police Chief Robert Gregoire said of the Gloucester program.

Gregoire is one of just two Maine police chiefs who are discussing bringing the program here (Jeffrey Lange, interim chief of the Paris Police Department in Oxford County, is the other), but more may become interested. Just last week, a new collaboration of treatment providers in Waldo County invited Campanello to speak at an event on Sept. 19 in Belfast.

The demand for heroin treatment has never been greater in Maine: The number of patients has spiked from 1,115 in 2010 to 3,510 people last year. In the last decade, the number seeking treatment for addiction to all opiates, including OxyContin and oxycodone, has more than doubled.

Yet cuts to MaineCare and other programs have made affordable treatment options hard to find. Two treatment centers have closed since spring. By contrast, Massachusetts is adding capacity.

Gov. Paul LePage has downplayed the need for more treatment and funding, and adopted a more tough-on-drugs philosophy that emphasizes enforcement over treatment.

That is part of what makes Campanello’s approach stand out: It is starkly different from the approach taken by LePage, who has even called in the National Guard to help enforce drug laws.

Campanello, when told of LePage’s plan, had a blunt response.

“Tell him good luck with that,” he said. “And tell him to come talk to me in two years when he hasn’t made a dent in the problem.”

ANGEL PROGRAM IS A ‘GAME CHANGER’

The city of Gloucester, about 100 miles south of Portland on Massachusetts’ North Shore, is home to just under 30,000 people.

It’s a community rooted in fishing – trawlers still fill the harbor, fishermen still unload their catch on docks – but also has been trying to brand itself a tourist destination, albeit a gritty one. Its economy is struggling, which has contributed to the growing drug problem. Like many cities throughout New England, Gloucester has seen the gradual transition from synthetic opiates to heroin.

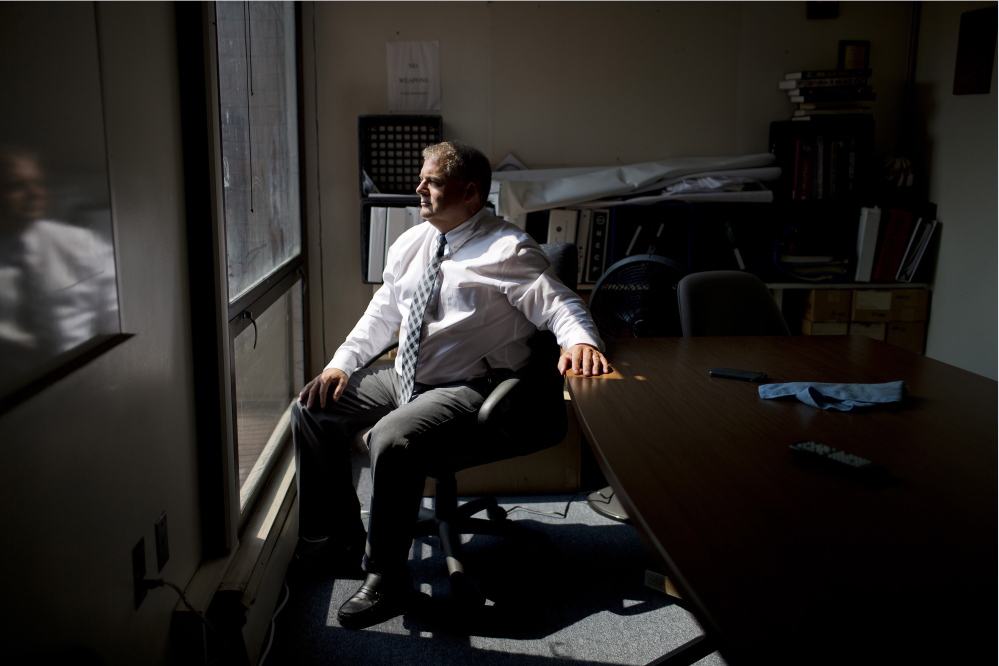

Campanello, a barrel-chested man with a deep, authoritative voice, has been Gloucester’s police chief for three years but spent several years as a narcotics officer in Saugus, a nearby community in Essex County. He has long watched the growing drug problem and its evolution.

The numbers in Gloucester have not been staggering compared to some cities – one overdose death in 2012, five in 2013 and four in 2014 – but Campanello reached his breaking point this spring.

After he received a call at home one night in early March about another heroin overdose death – the fourth, already matching last year’s total – the chief posted a message to the department’s Facebook page. He said he was committed to “continue to look for new ways to rid our streets of this poison,” and pleaded with addicts: “Let us help you.”

Campanello didn’t have an answer when he wrote the post, but his comment sparked discussion among treatment providers and others in the community. Overwhelmingly, the call was to encourage addicts to seek treatment, to stop treating them like criminals and to acknowledge that addiction is a disease.

Campanello’s next Facebook post in May laid out a plan in the same direct manner in which he handles other duties.

“Any addict who walks into the police station with the remainder of their drug equipment or drugs and asks for help will NOT be charged,” he wrote. “Instead, we will walk them through the system toward detox and recovery.”

Almost immediately, the idea caught fire. The Facebook post was viewed millions of times, bringing national attention to the Massachusetts coast.

John Rosenthal, who helped set up a nonprofit called the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative to aid with funding and to replicate the program in other communities, called the Angel program a “game changer.”

“A lot of people talk about doing something different. This chief drew a line in the sand and did it,” Rosenthal said.

Already, Rosenthal said, a dozen other police departments across the country have replicated Gloucester’s model.

“In a year, it will be a hundred or more,” he predicted.

AMNESTY FOR TREATMENT

Campanello’s approach is provocative because it effectively offers amnesty to drug users – only users, those whose only crime is addiction.

He said he’s playing the long game.

“If we can reduce the amount of people who are on the street suffering from this illness, … then we can improve the quality of life for everyone in the city,” the chief said.

The program launched on June 1 with no clear idea of what would happen next.

“We worried about zero people showing up. We worried about seeing a line of 25 people. We didn’t know what to expect,” said Lt. David Quinn, who oversees the program daily.

In the first three months, Gloucester has seen a steady stream of people asking for help and a treatment community that has wholly embraced its new law enforcement partner.

Marty Ginivan, who runs the Grace Center, a day program for low-income and homeless adults in Gloucester, is one of the 40 or so Angel volunteers. At first, Ginivan said, clients were apprehensive about the police department spearheading an effort to help them. But he said Campanello lent legitimacy and urgency to the need for treatment.

Ginivan said he’s seen success in small moments.

Last month, he met a young man who came to the police station seeking treatment. Ginivan asked if he wanted to call anyone before he was taken to a detox facility. At first, the man said no, but after a few hours, he asked to call his dad.

“So he calls and he puts the phone on speaker,” Ginivan said. “And he says, ‘Dad, I’m at the police station.’ And you can hear the silence on the other end, and you know the father has gotten that call before. But then the kid says, ‘I’m not in trouble. I’m going into treatment.’

“The dad told him he was proud of him. And just before he hung up the phone, the dad says to me, ‘Thanks for caring about my son.’

“That’s why we do it.”

Quinn said although each case is different, certain similarities have emerged. Most of the people coming in are men in their 20s or early 30s. And most don’t match the stereotypical description of a heroin junkie.

Instead, they look like Sandy, a 33-year-old man from Gloucester who asked that his last name not be used to spare his family embarrassment.

Sandy said the Angel program gave him a “kick in the (pants).” He was addicted to prescription opiates – Percocet – but likely was headed toward using heroin, which is cheaper than many prescription drugs.

“The day-to-day struggle of depending on something foreign to get through the day, I was thinking about it nonstop, it was my number one priority,” Sandy said. “I wanted to stop, but I couldn’t do it on my own.”

From the Gloucester police station, Sandy went immediately to detox. He didn’t sleep that first night in mid-August.

After six days, during which he began to wean off opiates with the help of methadone, he transitioned to a halfway house in southern Massachusetts where he still receives treatment.

He’s still working on his long-term plan.

“It’s a little strange having all this time to reflect, to get back to thinking about what you want to do with your life and what goals you want to accomplish,” he said. “Before, I would spend hours, literally hours, waiting around until I could get that next pill.”

ACCESS TO TREATMENT LIMITED IN MAINE

Campanello stresses that his department does not provide treatment itself and said he hopes policymakers commit the appropriate resources. The only money he commits is from his drug forfeiture fund and that’s to help patients with no insurance.

So far, volunteers and treatment providers have done the rest.

Quinn said Gloucester’s program has attracted clients from other states, including some from the Portland area. He said while his department won’t turn anyone away, the goal is for other departments to launch their own programs. That’s why the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative was established.

So far, the interest in Maine is still in the initial stage, but the program was lauded at a forum last month in Brewer organized by U.S. Sen. Angus King that featured U.S. drug czar Michael Botticelli.

Joel Merry, Sagadahoc County sheriff and president of the Maine Sheriffs Association, was among those who said the idea is worth pursuing. U.S. Attorney Thomas Delahanty said such programs work only if police departments have enough partnerships with clinics to steer people toward treatment.

Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck hasn’t ruled out such a program, but spoke cautiously.

“You need to look at what can work for your community and we’re looking at everything. We’re not sitting around waiting,” he said. “The problem of substance abuse tends to run in phases, but there is an urgency right how and it’s good to see the community interested – and I hope invested.”

In Augusta, Gregoire said his department is recruiting angels, or recovery coaches, to help steer addicts to treatment.

He said the key will be how much the community will support the effort.

“I think this has worked in Gloucester because an entire community has bought in,” Gregoire said.

Neill Miner, project director for the Alliance for Substance Abuse Prevention, a coalition of treatment and recovery organizations in Kennebec County, is working with Gregoire on the Augusta program.

“The emerging partnership between law enforcement and the recovery community is something we haven’t seen, at least at this level,” Miner said. “But in Maine, certainly compared to Massachusetts, access to treatment is far more limited and getting even more so. That is a concern.”

Chuck Faris, CEO of Worcester, Massachusetts-based Spectrum Health Systems Inc., one of several agencies working with Gloucester, said the Massachusetts government’s support of treatment is stronger than Maine’s.

“We’ve opened three new outpatient facilities in Massachusetts this year and are on schedule to open another,” Faris said. “We’ve done so because we’ve been encouraged by the commonwealth to respond.”

Faris said Spectrum never had that level of support in Maine. Last month, the company closed its first and only methadone clinic in Maine after only 18 months, blaming lack of support and cuts to MaineCare. The Massachusetts version of Medicaid, called MassHealth, offers much more comprehensive drug addiction treatment services than MaineCare.

Beyond that, Faris said he also can’t help but notice how differently Campanello and LePage have approached their states’ drug problem.

“I think sometimes it’s hard for people to get past their own biases and prejudices about addiction,” Faris said.

Campanello said he’s well past the point of judging addicts, and others say his commitment has drawn supporters.

“People are proud of the city and proud of the department. The chief can’t go anywhere without hearing about it,” Quinn said.

Campanello, however, downplays his role in shifting the debate.

“People have called this everything: brave, gutsy, revolutionary, groundbreaking,” he said. “Since when did extending a hand and helping someone in need, especially for police, become anything more than a responsibility?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story