GULF OF MEXICO – About two hours out into the Gulf of Mexico from the mouth of the Mississippi River, the epicenter of the BP oil spill comes into view.

At first it looks like several tall buoys hovering on the horizon, but as the slow-moving supply vessel approaches, the scene gradually re-forms. An oily sheen appears on the surface of the water and now 10 miles away the buoys have reshaped themselves into a cluster of soaring oil rigs, spewing flames from the excess gas being burned off.

The supply boat begins to throw up a wake of turquoise and muddy brown water as a fleet of skimming vessels appears ahead. Finally, four hours into the trip and 42 miles out, the Maine Responder, a 208-foot oil skimmer usually berthed in Portland Harbor, emerges between a sheet of rain showers.

“Welcome aboard,” said Capt. James Griffin of Portland.

The Maine Responder headed out of Portland on May 2 for the Gulf. Five Mainers are currently aboard, part of the 24-person crew, which includes both those responsible for the ship and its navigation and the workers involved in the skimming operations.

“We all pull together,” said Griffin.

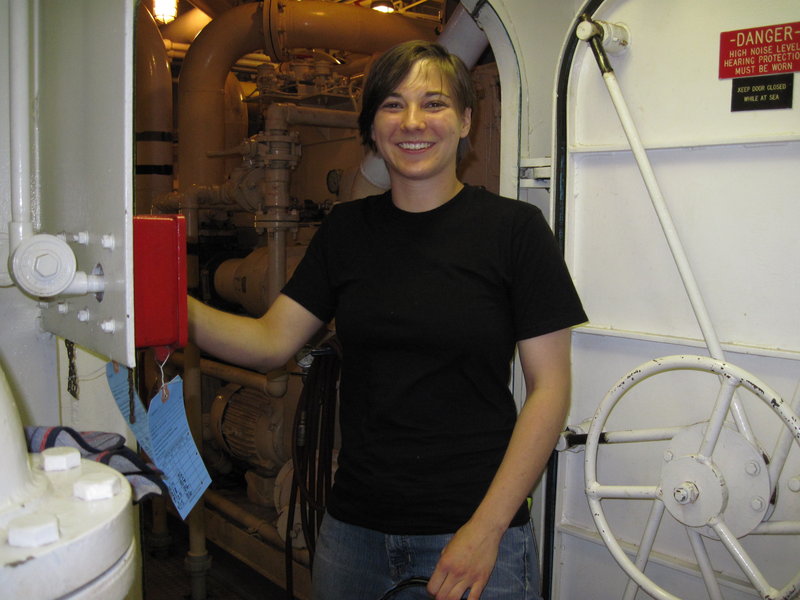

The Mainers are all involved in the navigation of the ship. In addition to Griffin, a native of Cliff Island, they are: engineer Tom O’Reilly of Cliff Island; assistant engineer Laura Wilcox of Cape Elizabeth, the only woman aboard; mate Dan Milligan of Portland; and seaman Brent Grimard of Gorham.

The Maine Responder is owned by the Marine Spill Response Corp., which was set up following the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, passed by Congress in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. The law required the creation of private companies, such as MSRC, to respond to oil spills. They are funded by oil companies. MSRC operates 15 oil skimming ships based at ports along the U.S. coastline. The closest one to Portland is in New Jersey.

MSRC’s oil response arsenal also includes airplanes, barges, a fleet of smaller boats, booms and other equipment, much of which has been assembled in the Gulf to clean up the oil spewing from a mile below the BP drill site.

The Maine Responder operates about a mile out from the site, dubbed “ground zero” by some. Griffin calls it “home plate.”

This is where some of the oil floats up to the surface. The area is surrounded by other skimmers performing the same task.

The Maine Responder can recover about 444,000 gallons of oil and water a day. First a 40-foot work boat with a two-man crew corrals the oil into a boom. Then the crew positions a skimming device in the pool of oil, which sucks it into one of the four 1,000-barrel holding tanks.

The oil floats to the top of the tank, and the water is removed from the bottom, making room for more oil. The water is treated and returned to the ocean.

The recovery operation is messy work done in sweltering conditions for the workers, who are dressed in thick overalls or protective suits, heavy boots and work hats. The temperatures are in the 90s and the humidity makes it feel 10 degrees hotter.

Before heading out, the two-man crew packs a cooler with several dozen bottles of water packed in ice.

The Maine crew’s job is to keep the ship moving slowly through the area as the work boat herds the thick brown oil.

“What it reminds me of is purse seining for fish,” said Griffin, who grew up in a lobstering family.

A barge comes and collects the recovered oil every few days.

The Maine Responder is visited several times a day by supply vessels such as the Mr. Leroy, which made the trip Friday morning with two visitors. The supply vessels carry food, water, equipment and passengers. The Maine Responder is equipped with a desalinization system but it is incapable of filtering out the oil from the water so every few days the boat gets a fresh infusion of drinkable water from a supply boat.

The Maine crew members form a tight-knit group. On Friday, when skimming operations were temporarily shut down due to a thunderstorm, they joked and kidded each other over a beef stew lunch.

Griffin, a Maine Maritime Academy graduate, is the subject of gentle kidding for his propensity to dispense his captain’s wisdom.

Wilcox, who has been on board since May 2 with no break, provides much of the banter, keeping the mood upbeat during long days.

“We are all used to looking at each other but then we go outside and realize we are not in Maine,” Griffin said.

They work in shifts around the clock, seven days a week. O’Reilly, who has been on the boat since it left port, just returned from two weeks back on Cliff Island. Grimard, who also came down on the boat, was able to get home for the birth of his daughter Bailey on May 28 in Maine.

When they are off duty, they sleep, play a lot of cribbage or hang out in the lounge with the other crew members and watch TV. There is no exercise room but Wilcox said going up and down the stairs all day provides a good workout.

The Mainers also visit Griffin at his post in the bridge, the coldest spot on the ship and the one with a dramatic 360-degree view of the oil spill disaster. The bridge is lined with state-of-the-art instrument panels. There is no steering wheel in sight. Everything is done by computer buttons, levers and joysticks.

The view from the bridge looks as if it could be a naval war zone. Several miles off, black plumes billow out from the controlled burning operations. Boats of all sizes zigzag between the skimmer vessels stationed like battleships across the horizon.

The crew watches the progress of two oil drilling rigs off in the distance, which are racing to drill relief wells that are expected to finally end the leak.

Word is from friends in Wilcox’s class at Massachusetts Maritime Academy, who are on the drilling rigs, there is a competition on to be the first to finish.

Griffin said the pace of the work was hectic when he first arrived. He had to get used to a half-dozen radios buzzing around him, helicopters flying back and forth overhead and all the other boats operating in the area.

But now the job has become more routine, even though his day starts at 3:30 a.m. And doesn’t end until 8:30 p.m., with only a few hours off in between.

“We call it ‘Groundhog’s Day,’ like the movie; we get up every morning and do the same thing,” said Griffin.

Despite the tedium, the Mainers said they feel that their work is important and they are taking part in a historic event. They say they are prepared to remain in the Gulf as long as they are needed.

“This is what we do, the career we went for,” said Griffin.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby may be reached at 791-6363 or at:

bquimby@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.