OLD ORCHARD BEACH — The yellow caution flag fluttered behind the lifeguards Tuesday as they looked into the haze, scouting the water for swimmers in trouble.

Plenty of them have been in distress in the past couple of days, here and at other beaches in southern Maine. Strong rip currents have been created by moderately large waves, astronomical high tides and, in some cases, new sandbars that have formed after a winter of severe erosion.

This summer, lifeguard captain Keith Willett is seeing more rip currents at Old Orchard Beach than ever before in his 16 years here. His team has handled at least 49 incidents since Sunday, compared with the handful they usually see on a day in a more typical week.

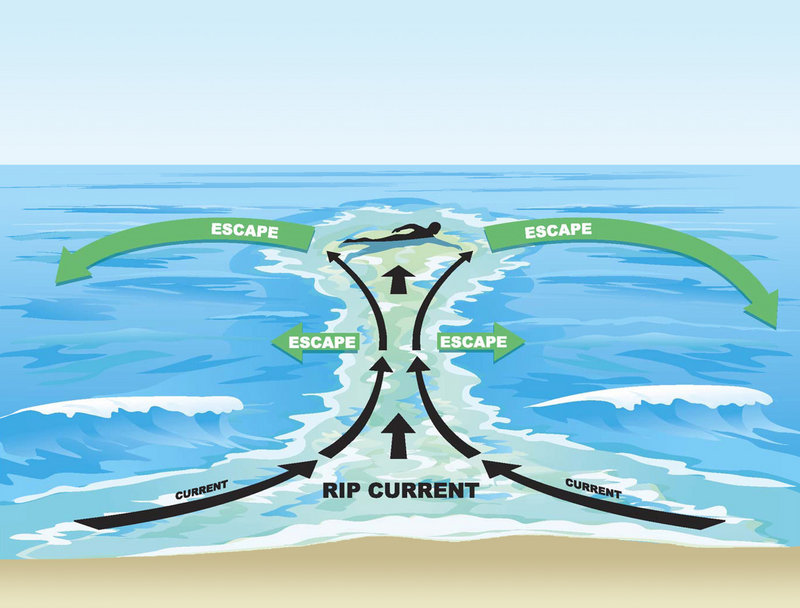

Rip currents, sometimes called riptides, are powerful channels of water that head away from land. The flow can be concentrated between sandbars and around structures such as piers.

Winter erosion dug ripples and contours into a stretch of Old Orchard Beach that lifeguards call the “playground.” In past years, receding tides uncovered a 100-yard-wide stretch of hard, smooth sand along that stretch.

Dan Mahoney found himself in the grip of a rip current while body boarding Monday afternoon. The 47-year-old carpenter from Worcester, Mass., had gone out a bit farther than usual to catch the breaking waves, and suddenly realized that he was twice as far from shore as he had thought.

Mahoney paddled and paddled against the tide without making much progress. He got a little nervous as he started to tire. Two lifeguards got to Mahoney just as he reached cresting waves that brought him back to shore — safe but blue-lipped from the cold water.

“It’s scary when you turn around and know you’re out too far,” Mahoney said Tuesday.

In Wells, lifeguards had eight rescues and about a half-dozen less serious incidents Monday, even though visitors were prohibited from going more than waist-deep in the water during the afternoon.

The combination of rip currents and poor visibility led to a similar restriction Tuesday until 2 p.m.

Typically, Wells’ lifeguards have one or two incidents a week, and some days end without any, said Brittany White, the lifeguard captain.

“So it really was a shocker,” she said, to see so many swimmers get in trouble.

The managers of Reid State Park in Georgetown and Scarborough Beach State Park said rip currents have been strong recently. Other spots, including Popham Beach State Park in Phippsburg and beaches in Kennebunk and York, have not had the same problems.

Any large beach system, particularly a long, linear one, can develop strong rip currents, said Stephen Dickson, a marine geologist with the Maine Geological Survey.

Dickson said the location of sandbars can affect rip currents from year to year. Sand makes its migration toward land from about May to September.

In the shorter term, swells have a bigger effect on rip currents, he said.

Conditions for continued high surf aren’t expected today. In fact, the wind will change direction and knock down the surf, said Eric Sinsabaugh of the National Weather Service in Gray.

“Things are generally quiet out there,” he said. “Will be for the foreseeable future.”

Staff Writer Ann S. Kim can be contacted at 791-6383 or at: akim@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.