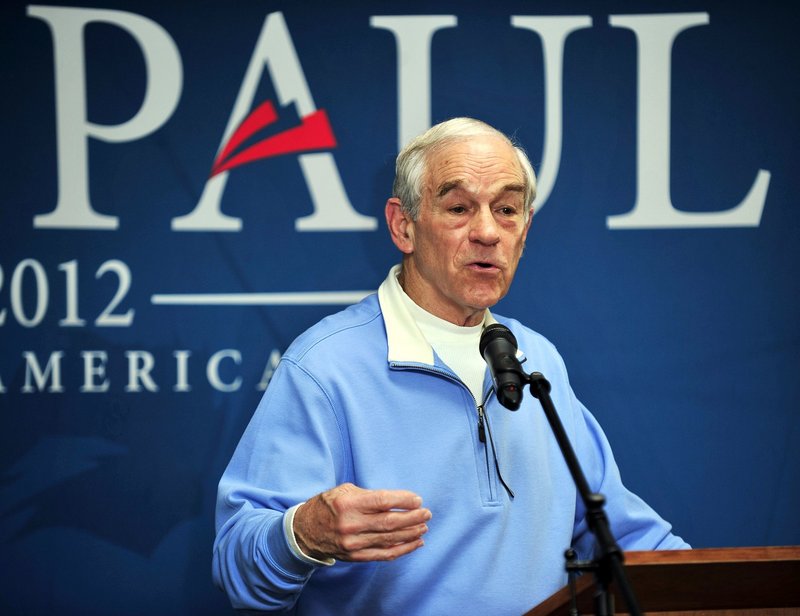

What, exactly, is Ron Paul up to? The Texas congressman has, by all reasonable reckoning, lost his bid to be the Republican presidential nominee. Lost it big. In the GOP’s 35 primary and caucus votes, Paul has won as many as President Obama. Zero.

But now, Paul is using an unorthodox tactic to add more delegates to the national convention this summer. In Nevada, Maine, Massachusetts and elsewhere, his supporters have flooded the party’s snoozy state conventions — and then elected themselves to delegate slots.

That’s prompted a question now transfixing the GOP: What does Paul want?

Paul still has little shot at the nomination. But, with these numbers, the perennial outsider could gain enough leverage to demand a speaking slot, or changes to the party platform at the convention, if GOP bosses fear that Paul’s unhappy fans could disrupt their big moment.

“What are we supposed to do? Tell these people, ‘Look, the poor (Mitt) Romney campaign isn’t organized. They don’t know how to do this. We ask you that you please vote for Romney’?” said Doug Wead, a historian and a senior adviser to Paul’s campaign.

Wead’s answer was no. Instead, Wead said he hoped that Paul’s additional delegates would win him a formal delegate vote on his nomination and a speaking slot in the convention’s spotlight. That could help raise Paul’s profile, and the profile of the son — Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky. — he is grooming for bigger things.

“It’s already too late” to stop Paul’s strategy from working, Wead said. “We’re going to have a ton of people on the floor of the Republican national convention.”

In an interview with CNN on Wednesday, Paul said of his continued campaign: “It certainly isn’t for the reason of disrupting the convention. I’m in it for very precise reasons: to maximize our efforts to get as many delegates as we can. I’m still a candidate, and to promote something that is very, very important, that is a change in the direction for the Republican Party.”

By the numbers, the GOP race looks as finished as the Civil War.

Romney has an estimated 919 delegates, nearing the 1,144 he needs to win the nomination. Paul has just 100, less than ex-candidates Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich.

But Paul, unlike those two, is still fighting. Last weekend, for example, Paul’s fans were so successful at the Maine state convention that they added 20 delegates to his total. Romney — who had won Maine’s caucuses in February — got two.

Romney’s camp professes to be unworried.

“Make no mistake that the Tampa convention will nominate Mitt Romney, and it will be his convention,” Andrea Saul, a Romney campaign spokeswoman, said in an email. She said Romney “has a lot of respect for Dr. Paul and the energy his supporters bring to the process.”

But privately, some Romney advisers say Paul’s convention tactics have become a distraction — diverting time and personnel at a time when Romney wants to shift his focus to Obama. In Maine, for instance, Romney sent one of his top lawyers to try to counter the Paul camp’s procedural tactics.

The idea behind Paul’s “delegate strategy” is to exploit the difference between what the GOP nominating process looks like and what it really is. What it looks like is a rolling series of miniature election days, with attack ads, flag-waving rallies and statewide votes.

It really is an eye-glazing, posterior-numbing series of meetings.

These usually happen after the votes: Local conventions elect delegates to state conventions. State conventions elect delegates to the national convention. Then, in Tampa in August, national delegates will cast the votes that choose the nominee.

In nine states, the first step determines the later ones: All delegates are “bound” to vote for whomever the voters chose. But in the other states, delegates are split between candidates. Or they are allowed to ignore the voters and choose for themselves.

For Paul, that means a battle lost at the polls can be refought in a hotel ballroom.

“They stepped off the field after the first inning. We stayed on the field,” said Carl Bunce, Paul’s campaign chairman in Nevada. In February, Romney won Nevada’s statewide caucuses by 30 points. But at the state’s series of conventions, the Paul campaign got its people in 22 of the state’s 25 delegate slots.

That’s not as big a victory as it sounds: 14 of Nevada’s delegates will still be “bound” to vote for Romney on the convention’s first ballot.

But Bunce said there’s always a chance that Romney won’t win on the first ballot. And even if he does, Paul’s people will be able to clamor for policy priorities, such as stopping foreign wars, radically shrinking the government or auditing the Federal Reserve.

“It’s kind of movement versus moment. The moment here is the 2012 campaign. But we’re also trying to build a strong liberty movement” for the future, Bunce said.

“We’re not going to be let down by a moderate like Mitt Romney being our nominee.”

Paul’s people hope to win similar victories at conventions in Minnesota, Iowa, Louisiana and Washington.

As Paul’s numbers grow, so does his ability to disrupt the convention’s rituals of Republican unity: His supporters might be able to put Paul forward for the nomination or vote against the GOP’s official platform.

“The Paul folks don’t necessarily have to play the usual game. And by at least holding the threat of embarrassing (Romney) at the convention, they can hope to leverage something,” said Josh Putnam, a professor at Davidson College in North Carolina who studies the minutiae of delegate selection. “What that is, I have no earthly idea.”

But so far, Paul’s campaign has not threatened this kind of disruption. The reason, Paul’s advisers said, is that Paul’s long-term goal is not to fracture the GOP, but, over time, to remake it in his libertarian image.

It would be counterproductive to embarrass other Republicans with a screaming-match convention that weakens the party’s nominee.

Seen in that light, what does Paul’s delegate strategy mean?

“The future. The sun also rises. I’ll put it that way. It means that congressman has a son who’s a U.S. senator. That’s what it means,” said Wead, Paul’s senior adviser.

Maybe that son could be a presidential candidate someday? “Now, I won’t say that,” Wead said. “But that’s a good point.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.