The owners of Five Fifty-Five in Portland have worked with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute for a couple of years now.

Steve and Michelle Corry participated in GMRI’s Out of the Blue program last year, making it a point to place under-used fish from the Gulf of Maine on their menu to give overfished species a break.

And they always have a drink on their menu dedicated to the organization; every month, a portion of the sales of that drink are donated to GMRI.

Now, Five Fifty-Five has gone a step further by joining a new program GMRI has developed called Sustainable Seafood Culinary Partners.

Culinary Partners, which began in February, has a list of requirements that restaurants have to meet to join, and members must commit not only to seafood-centric goals but also goals that focus more broadly on sustainability. Think more energy-efficient refrigeration and composting and less water consumption.

“For me that’s great, because as a business owner you want to do such things,” Michelle Corry said, “but you’re often mired down with day-to-day stuff that you’re not necessarily thinking, ‘OK, what can I do now to be more sustainable?’ They’re actually throwing down the gauntlet and saying you have to think of something.”

Samuel Grimley, sustainable seafood project manager at GMRI, said the institute has been planning Culinary Partners for a little over a year now, and held a couple of feedback meetings with restaurateurs to get their input as the program was developed.

Since February, five Maine restaurants have joined up and set goals for themselves for the coming year. In addition to Five Fifty-Five, the other members are Sonny’s and Local 188 in Portland, Sea Glass at Inn by the Sea in Cape Elizabeth and the Jordan Pond House restaurant on Mount Desert Island.

“We really would love to see the program grow and be expanded to other restaurants, even if the restaurants are down in Massachusetts or other areas,” Grimley said. “We don’t have to limit it to just Maine. We’d love to see these restaurants kind of work collectively to raise awareness of Gulf of Maine seafood.”

COMMITMENT BY RESTAURANTS

Restaurants that join Culinary Partners must agree to:

• Commit to sourcing at least 20 percent of the seafood items on their menus from the Gulf of Maine.

n Include a minimum of one species of local seafood on their menu that has been verified as responsibly harvested.

• Meet annual requirements around improving sustainability of their business operations. The restaurateurs themselves set these goals, with help from GMRI staff.

• Send up to three staff members to a four-hour sustainable seafood education seminar each year.

• Pay a $500 annual fee, an amount that was set with input from local restaurants.

• Explain to their customers what they are doing and why.

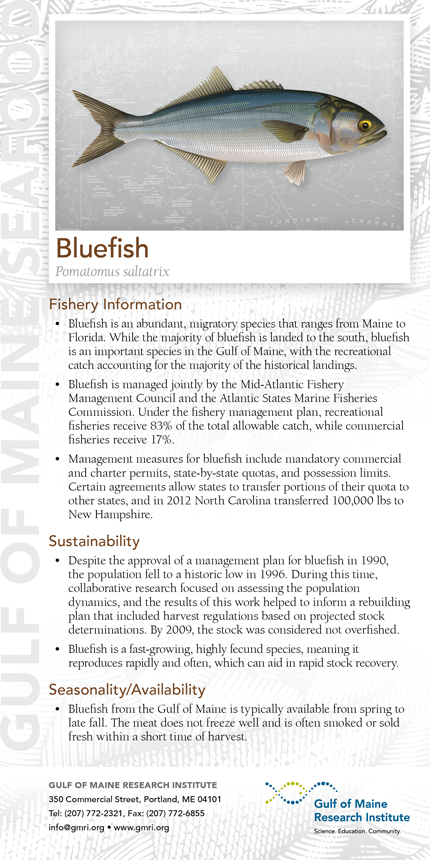

GMRI prints rack cards that have an overview of the program and a list of all species that are harvested locally. The cards will be given to the restaurants and posted at tourist centers. The restaurants also get “species cards” they can give to customers that show what a particular fish looks like and explain how the species is faring and how it is managed.

The bluefish card, for example, explains that bluefish are not considered overfished and they are typically available from spring to late fall.

“The meat does not freeze well and is often smoked or sold fresh within a short time of harvest,” the card reads.

Restaurants also receive a monthly newsletter covering both research news and culinary trends in seafood.

The latest edition contains information on federal legislation that would address the mislabeling of seafood, notes about the scallop and shrimp seasons, and links to seafood-related events and news stories.

SEAFOOD AT JORDAN POND

Popovers are the iconic menu item at the Jordan Pond House on Mount Desert Island, but the restaurant is just as well known for its lobster stew and other seafood dishes.

Michael Daley, who manages the restaurant, says about 35 percent of its food budget goes to seafood. There’s a laser focus on local species. All of the restaurant’s scallops and shrimp, for example, are purchased and frozen during scallop and shrimp season so they’ll be available year-round.

“We buy an awful lot of lobster meat, lots of scallops, Maine shrimp,” he said. “We used to buy a lot of haddock when you could get haddock, and now we’re substituting for that with under-utilized species like hake and redfish, monkfish, the kind of things that the Gulf of Maine Research Institute is promoting as an alternative to some of the overfished species.”

The Jordan Pond House is already part of an environmental program through its association with the national park system. An outside firm comes in every year to audit the restaurant and make sure it is meeting its goals for recycling, waste reduction and composting. (Daley says they go through “cases and cases” of lemons to make fresh-squeezed lemonade, and all those spent lemons end up as compost in the restaurant’s gardens.)

With such a good track record already, why does the restaurant want to join Culinary Partners?

Daley said the Jordan Pond House is “always working on extending that reach for local products.”

“We’ve pretty much been 100 percent successful in seafood,” Daley explained, “but we are very reliant, for example, on Port Clyde seafood, so we would like to develop some other sources.

“And I think that’s going to be a moving target with seafood in the Gulf of Maine. Every year there are new limitations, there are new fishing methodologies and so forth, and that’s something that, in the restaurant business, it’s awfully hard to keep track of all that.

“So one of the attractions in being associated with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute is that’s what they’re doing all the time. They’re experts on that. They know which fishing methods are being developed that make the most sense. They know which species make the most sense to be trying to utilize, and so we’re kind of relying on them to provide that kind of information.”

A BOON TO FISHERMEN

Daley said he’s also hoping the program will grow beyond the handful participating now, because the more restaurants that participate and buy locally, the better it will be for struggling fishermen.

“The guys who are fishing along the Gulf of Maine, they’re having an awfully hard time,” he said.

At Five Fifty-Five, Michelle Corry estimates the restaurant sources 80 percent of its seafood from the Gulf of Maine.

The restaurant already recycles and sells all its cooking oil. So the Corrys have set a goal of starting a composting program, which they have wanted to do for a long time but have had trouble finding the space.

The Culinary Partners program, Corry said, “kind of gets you off your butt to do the right thing.”

“They’re very open-minded,” she said. “They take into consideration all aspects of the sustainability chain — the restaurant, the fisherman, the government. They’re not just coming at you. They get that it’s a business, and we have to make some money to survive.”

Having said that, restaurants that participate are expected to follow the rules.

Restaurants have to submit quarterly reports of their progress during their first year in the program, then annually after that.

GMRI staff will visit regularly to make sure they are in compliance with the guidelines. If they get three violations in a row, they’re kicked out of the program for a year and their fee is not refunded.

Rauni Kew, who works on the green programs at the Inn by the Sea, says the hotel is a “huge supporter” of Culinary Partners.

“I can’t imagine Maine without a fishing industry,” she said. “It’s so important to the Maine tourism industry, and of course we have lobster boats out here bobbing on the horizon when you’re sitting in Sea Glass dining, so supporting the fishermen in any way that you can when they’ve been so hammered with all of these restrictions is also a no-brainer for us. It’s the right thing to do.”

Kew said Sea Glass chef Mitchell Kaldrovich already sources most of his seafood locally; his goal is to reach 100 percent. Under-used species are already regulars on the restaurant’s menu, and there is only Gulf of Maine seafood in the paella.

Kew is most excited about the opportunity to educate and engage diners about species that are in trouble, and get them to “broaden their palates” by trying alternatives to foods like cod and haddock.

“When we say to them, ‘Why not try whiting’ or ‘Why not try redfish’ or ‘Why not try pollock’ today, and then they question it, we tell them the story of how difficult it is for the Maine fishermen right now, so it’s important to eat other fish,” she said. “And then we bring out these cards. It really adds value to their dinner. They become involved with the fishermen’s story.

“It’s a Maine story.”

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.