Mary Rolph Lamontagne can show you how to take that bit of leftover red cabbage taking up space in the fridge and turn it into soup. Or Asian chicken salad. Or fish tacos.

You get the idea.

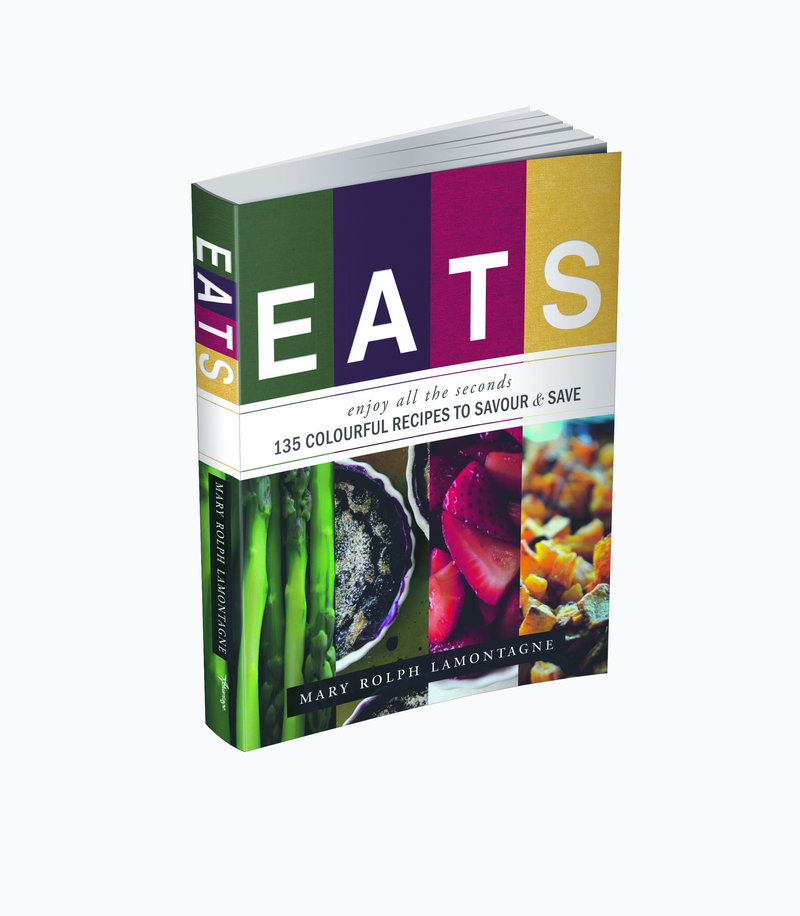

In her new book, “EATS: Enjoy All the Seconds” (Advantage, $29.99), she does the same with strawberries, zucchini, eggplant, butternut squash, spinach — all those leftover fruits and vegetables that end up rotting in your crisper because you either bought too much or don’t know what to do with them.

A resident of Prouts Neck and South Africa, Lamontagne was inspired by what she learned while working as a chef in South African game reserves, and was motivated by some shocking statistics. On average, she discovered, North Americans throw out 40 percent of the food that they buy or grow, and 23 percent of all methane emissions come from uneaten, decomposing food.

A native of Montreal, Lamontagne graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont and then attended the Ritz Escoffier Culinary School in Paris. She has worked as an event planner and a food journalist.

Lamontagne moved to South Africa in 2005, when her husband started a non-governmental organization there for entrepreneurs, but she still spends summers in Maine. She has worked as a food consultant for the Protea Hotel group and various upscale game camps.

After speaking with the Maine Sunday Telegram from her summer home, Lamontagne planned to go dumpster diving in New York to film a documentary for her website, savourandsave.com.

Q: So who’s cooking in game reserves?

A: Usually, there’s a young chef who has some sort of knowledge, but most of the prep work and a lot of the people who are cooking are from the villages around the camps. The bush camps are expensive. It’s mostly North Americans and Europeans, and they want to eat good foods, and a lot of them are somewhat picky.

We get a list before we start about what are your preferences and what are you allergic to, and what can you eat? It’s amazing how many people are either gluten-free or gluten-intolerant or don’t eat this, don’t eat that.

And we only get food delivered once a week, so you really have to be creative with the way you create your menus. Often, there will be a last-minute booking where the person is allergic to everything. It’s happened so many times, and you have to really go through the fridges, the cupboards, and say, “OK, what are we going to do this week?” And you can’t repeat as well, right?

Most of these villagers who are living around the camps don’t really eat Western food, so I started to realize that a lot of them were cooking, but they had no idea what they were cooking. They didn’t want to taste it. Part of my whole belief system is that anything you make, you need to taste. And so I got people to tasting and understanding why you do one thing or another. And then they taught me things as well with different recipes they had, and I started to work with them and incorporate their ideas and my ideas. It’s been a great journey, actually.

Q: It kind of sounds like what they call “glamping” now. Glamorous camping.

A: It is. People will pay up to $1,000 a night to stay in these game reserves. They get fed four to five meals a day, so you really have to be on your game. Rusk in the morning is something that’s very typically South African. That’s a really hard biscuit that you dip in coffee, and it sort of fortifies you. Everybody has a different recipe for that. That’s how you start the day, and then fruits and tea when you stop to have a little break. Then you come back, and you have a major brunch/lunch thing. And then you have a nap for four hours, and you come back and have another lunch/tea with cakes.

My butternut (squash) cake from my book; it’s cake that I created in the bush camp because butternuts and beet roots are two of the favorite things for South Africans to serve, and we had so much butternuts and beet roots that I created this butternut cake for a tea. It’s great. It’s really yummy. But that was created out of not knowing what to do next.

Q: You were working in a bush camp in Botswana when you had your “a-ha” moment about using leftover foods. What happened?

A: That was my butternut “a-ha.” The other thing was, the hyenas had come in at night and eaten all the sugar in the camp because we hadn’t closed it down properly. And (more) food wasn’t going to be delivered for another two weeks. You can go to other camps, but it’s three to fours hours away. You can fly in, but that’s expensive.

We started going through the root vegetables, and we had carrots and butternut. There were people flying in for tea, and I was like, “OK guys, we have got to do something.” We had roasted butternut from the night before for a roasted butternut salad. So I just said, “Let’s just use this leftover. Let’s figure it out.” And that’s how we got on our way.

I come back to Maine every summer, and for the first 10 days, I would just shake in my boots because oh my god, there’s so much waste. Anything from going out for dinner, and (there’s) way too much food, to the packaging and even my (own) waste. Here, I’m buying from markets and stuff like that.

There’s such an amazing array of fruits and vegetables here and colors, that you sort of get carried away. Then you get home and you’re invited out for dinner, and all of a sudden you have all this food that’s building up.

I started thinking about how my life is so different here compared to South Africa, and then I was trying to figure out why, and then I realized we waste so much food here, and that’s how this whole thing started.

Q: What are the most common foods that are thrown out here in the United States?

A: If you look at them, they’re really fruits and vegetables that you use on a regular basis. Butternut and beet and cabbage, carrots and peaches and plums — those are all the things that, when I think of summer or winter, I always think of those things. I think of apple picking or strawberry picking. They’re all the things we come home with bags full of stuff. Or tomatoes at the end of the summer. In the past, you’d be canning or making applesauce, and doing all sorts of fun things, and I don’t think we do that as much.

Q: What are the overall messages you want people to get from this book?

A: One is to start thinking about what we’re putting into the bin, and to try to come up with solutions for the amount of waste we’re creating by eating what we have in the fridge and not overbuying and not impulse buying. Probably the best thing is, when you go shopping, make a list and stick to the list so you don’t buy excessive amounts of stuff and you reduce the amount of waste you’re creating in the kitchen.

If you do have leftovers, see them as treasures and not as things that go in the garbage. Try and celebrate using the leftovers rather than just going “ooh, yuck” and throwing them out. Those are probably the biggest things.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.