Bonfires lit up the night sky on Feb. 22, 1864, as residents of Portland and Cape Elizabeth celebrated George Washington’s birthday, unaware of the large ship steaming toward them.

Two miles offshore, most of the passengers aboard the RMS Bohemian slept as the ship neared the end of a long, rough crossing from England. All was peaceful on board until the veteran ship captain suddenly found himself and the ship in a “peculiar haze” that proved both disorienting and disastrous.

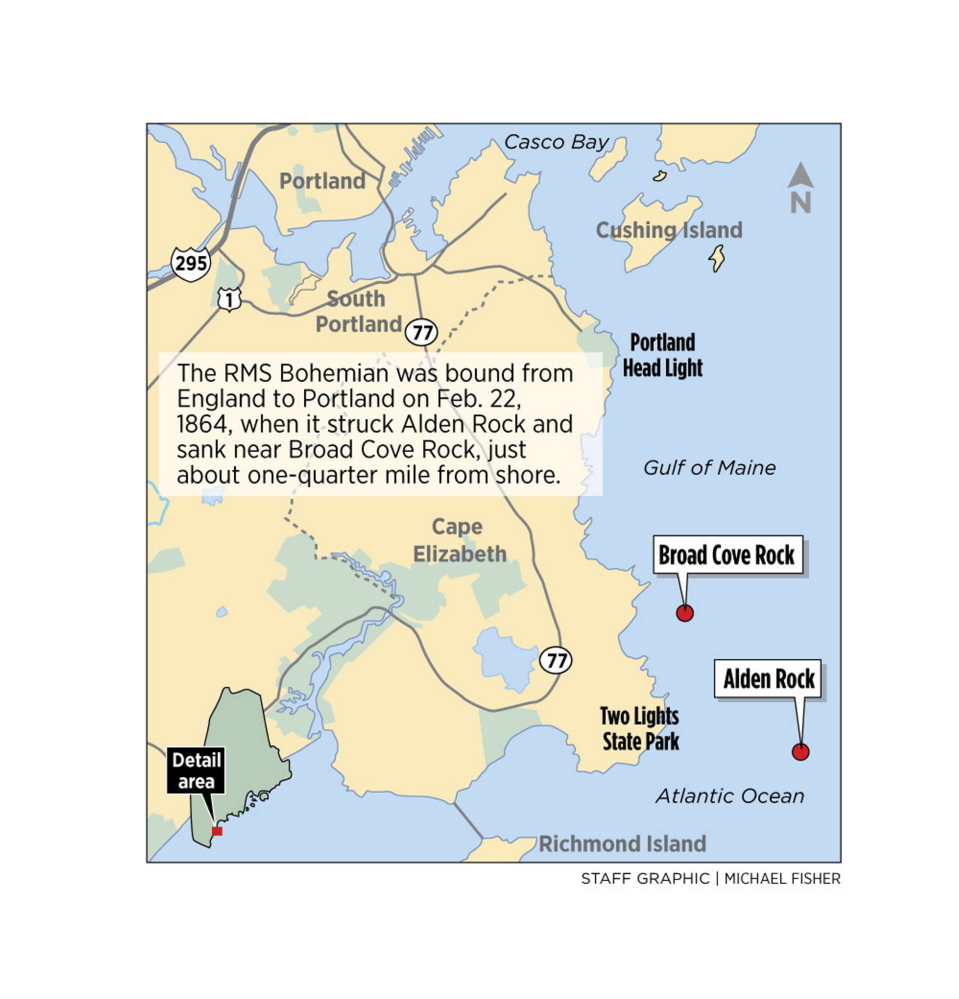

By the end of that night, the ship would strike Alden Rock, an underwater ledge off the coast of Cape Elizabeth. Forty-two people drowned, most of them Irish emigrants planning to start new lives in Boston, New York or Quebec. The ship’s cargo spread across Casco Bay.

Back on shore, local residents mistook the distress flares and gunfire from the sinking ship as part of the holiday celebrations.

It would remain, even 150 years later, the worst shipwreck ever recorded in Casco Bay and one of the worst along the Maine coast. But except for a few reminders scattered around Greater Portland, it is largely forgotten.

“As a general rule, the story of the Bohemian is relatively unknown,” said Matthew Jude Barker, a local historian and author.

Barker will recount the harrowing tale of the Bohemian during a lecture at the Irish Heritage Center on Saturday, the 150th anniversary of the shipwreck. The free event, which begins at 2 p.m., will feature Barker talking about the ship and its connection to the history of Maine’s Irish community.

DISORIENTED BY ‘PECULIAR HAZE’

It was a calm winter evening in 1864 as the Royal Mail Ship Bohemian headed toward Casco Bay, loaded with $1 million in silk, pottery and other cargo, 218 passengers and 99 crew members.

The three-decked ship was 295-feet long. It was steam-driven but also had three masts and sails for propulsion.

Most of the passengers aboard were Irish emigrants, traveling in steerage compartments with all of their belongings and dreams of a better life in America or Canada.

The Scottish-built ship, slowed by bad weather, was 18 days out of Liverpool and five days overdue to reach Portland.

Capt. Robert Borland had sailed into Portland nine times before. But on this night, he would say, he found himself disoriented by a “peculiar haze” a few miles off shore. Other survivors would also describe the haze. Borland set off rockets and flares in an attempt to summon a pilot boat, not realizing he was so off course that his signals for help would go unnoticed.

A pilot boat, expecting the overdue Bohemian, was elsewhere in Casco Bay looking for the larger, three-masted ship, but was unable to find it. Borland, thinking the ship was five miles off the coast of Cape Elizabeth instead of three, continued toward land.

Then, without warning around 8:30 p.m., the belly of the ship struck Alden Rock hard enough to rip open its iron hull. The ship, then nearly two miles southeast of Cape Elizabeth, began rapidly filling with water.

Recognizing how dire the situation was, Borland ordered the ship to go full steam toward land. It was a move later credited with saving many lives.

The sinking steamship wallowed toward Cape Elizabeth for nearly a half-hour before coming to Broad Cove Rock, another underwater ledge about a quarter-mile from Maxwell’s Point. Borland ordered both anchors dropped and told his crew to start evacuating passengers.

But those passengers, groggy with sleep and stricken by fear, panicked.

SOME ESCAPE, SOME LEFT ON SHIP

In their rush to get off the ship, 16 people jumped aboard a lifeboat too soon, snapping a pin and sending them plunging into the icy water.

“A cluster of frenzied souls was unexpectedly pitched into the black ocean water where 16 quickly perished. The next day the overturned boat was found on shore containing the bodies of a man and a child,” author Peter Dow Bachelder wrote in “Shipwrecks and Maritime Disasters of the Maine Coast.”

The ship’s other lifeboats were successfully launched and carried shivering passengers to the beach. When the last boat was gone, nearly 80 people remained aboard the wreck as it tossed in the waves.

Some passengers were so panicked at being left behind that they jumped into the water, including a mother who first strapped her infant to her shoulders.

The remaining passengers clung to the half-submerged ship, the deck steeply sloped toward the water below. Borland led a group of women and children into the foretop, the platform at the top of the foremast.

The remaining men climbed up into the rigging. Two men strapped their 61-year-old mother to the mast to save her as they waited hours for lifeboats to return, Barker said.

At 10:30 p.m., the ship sank in 30 feet of water, with only a small section remaining above the waves.

Finally, around midnight, the lifeboats returned for the stranded passengers. The 61-year-old woman was among those rescued from the rigging. She would live another 40 years, according to Barker.

CAPE COMMUNITY RUSHES TO HELP

Borland and the few officers still aboard the ship rode the last lifeboat to shore.

On land, they found two communities scrambling to help strangers left stranded and destitute by the wreck.

“Neither the sound of the Bohemian’s guns nor the glare from her rockets and flares had attracted much notice along the sparsely settled section of Cape Elizabeth shore opposite where the steamer sank,” Bachelder wrote in his book. “It wasn’t until the first of the several lifeboats bearing cold and bewildered shipwreck victims had landed that news of the tragedy spread throughout the vicinity, precipitating a spontaneous outpouring of humanitarian acts.”

Cape Elizabeth residents built bonfires along the shore to warm the passengers, then offered them food and shelter. Many of the passengers had nothing but the clothes on their backs.

“The only people who drowned were the very poorest emigrants on the ship,” Barker said. “It was definitely chaos after, when they didn’t know who had survived and who didn’t.”

Bodies washed ashore for days after the wreck. Workers set up an emergency morgue in the blacksmith shop of the Ocean House hotel in Cape Elizabeth, while others brought survivors into Portland. There, Mayor Jacob McLellan provided apartments to many victims in the new City Hall on Congress Street.

Businessmen in the city immediately kicked off a relief fund, raising $700 in the first three hours, according to Bachelder.

Many of the emigrants who survived the wreck eventually continued on to Boston, New York and Quebec, Barker said. But the bodies of 30 victims remained unclaimed in Maine.

Twelve victims were buried in an unmarked grave at Calvary Cemetery in South Portland. The rest were laid to rest in a pauper’s grave at Forest City Cemetery.

SHIP’S CARGO FLOATS ASHORE

Although there were rumors that Capt. Borland was drunk the night of the wreck, an inquest would later find that the crew of the Bohemian was not at fault, Barker said.

“The captain tried to do the right thing,” said Nathan Lipfert, senior curator at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. “It could have been much, much worse. If he had gone down in deeper water, there would have been a much greater loss of life.”

In the weeks after the wreck, the ship was pulled apart by waves, spilling sacks of mail and the $1 million worth of cargo into the water. For days and days, residents headed to the beach to collect pottery, reams of cloth, buttons and other items washing ashore.

“Some of the pewter and cloth, gold embroidered silk, is still to be found in the houses on the Cape as it has been handed down from family to family through the years,” according to a Maine Sunday Telegram article published in 1940. “Even after a lapse of 76 years, some of these pieces retain much of their original luster and quality.”

Lipfert said people rowed out in boats to collect debris and items from the ship. A newspaper article would later say that every child in Cape Elizabeth had a new pair of shoes that year.

Yet there are no known remaining artifacts from the Bohemian on public display. In the entire 50 years that it has been collecting items, the Maine Maritime Museum has never come across anything from the ship.

“It’s very surprising there isn’t more stuff around,” Lipfert said. “The shipwreck was a big story at the time, but it faded from memory fast.”

RECOGNIZING EMIGRANT VICTIMS

For 120 years, the Bohemian tragedy remained nearly forgotten until a local postal worker took notice of the “Shipwreck at Night” mural painted by Alzira Peirce in 1939.

Bartley Conley, who worked at the South Portland post office for many years, began asking questions in the early 1980s about the mural of the Bohemian painted on the post office wall. When he learned that many of the victims lay buried in an unmarked common grave at Calvary Cemetery, he launched an effort to raise $3,500 for a stone Celtic cross to erect in their honor.

Conley told the Sunday Telegram in 1984 that he felt compelled to do something after learning most of the victims were Irish emigrants.

“My mother and father came by ship to this country. … I put them in that boat – those people on the Bohemian, they were human beings, babies and middle-aged and elderly,” he said. “They left Ireland to seek a better life in America. My mother and father were fortunate enough to make it here, but there were a lot of others who didn’t.”

Today, the Bohemian cross stands in a quiet back corner of Calvary Cemetery in South Portland, tucked away from the busy intersection of Route 1 and Broadway. The simple monument lists the names of most of the victims buried there, including 41-year-old Thomas McDonough, his wife, Mary, and their children Patrick, Thomas and Mary. Only one of the people buried there is not named. The engraving at the bottom of the list says only: “child (little girl).”

Less than a mile away, the other 18 unclaimed victims of the wreck are buried without recognition.

Barker, the historian, wants to change that. He and other members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, a fraternal order of Irish Catholics, are planning to raise money to mark the grave with a simple monument recognizing the tragic end to their quest for a new life in America.

“This is a poignant story that should be well known,” Barker said. “For these emigrants to be so close to shore and drown is a tragedy that should be remembered.”

Gillian Graham can be contacted at 791-6315 or at:

ggraham@pressherald.com

Twitter: @grahamgillian

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.