Korczak Ziolkowski, a Polish American sculptor, once joked that he was “the world’s biggest chiseler.”

Few would have disputed the description of a fiery-tempered man who devoted half his life to carving a monument to the Sioux warrior-chief Crazy Horse that promised to dwarf the presidential heads at nearby Mount Rushmore.

The work would be colossal, perhaps the largest modern sculpture in the world.

Ziolkowski (pronounced jewel-KUFF-ski, first name CORE-chok) began the task in 1948 after buying a granite peak in the Black Hills of South Dakota that he named Thunderhead Mountain. Crazy Horse defeated the cavalry of Col. George Armstrong Custer during the 1876 Battle of Little Big Horn, but he was bayoneted to death the next year by a white soldier.

While Ziolkowski went about his undertaking on a shoestring — he refused offers of federal funding, saying it would be an insult to American Indians — he was supported unconditionally by his wife, Ruth, who died Wednesday at 87.

She lived with him in a log house, bore 10 children and tended to the museum and gift shop near the planned monument.

She also tended to his tempers, which struck as often as the lighting on Thunderhead Mountain. “He can still rant and rave and yell,” she once told Newsweek. “It’s when he’s not talking that we all get worried.”

Curious passers-by stopped in to see the couple and helped underwrite their quixotic fixation, leaving a few dollars at a time.

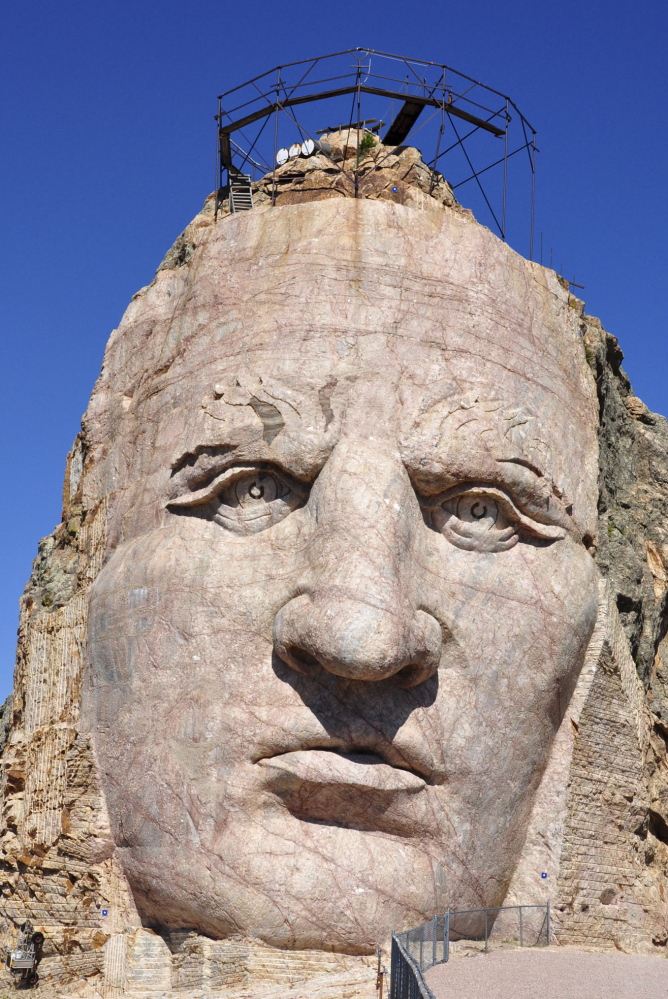

Korczak Ziolkowski designed the sculpture to be 641 feet long and 563 feet high — higher than the Washington Monument. It will depict Crazy Horse astride a wild stallion and pointing east in tribute to the burial place of many Sioux.

The four presidents on Rushmore are 60 feet high. The Crazy Horse Memorial stallion’s eyeball alone is about 30 feet across.

Korczak Ziolkowski died in 1982, at 74, with much of the outline of the horse and rider visible but no finished sculpture. Ruth, who had made an art form of stretching a nickel, succeeded her husband as chief executive of the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation and helped redirect efforts toward faster completion.

For years, her husband had focused on carving the stallion, but Ruth Ziolkowski felt it would speed fundraising if the face of Crazy Horse were done first. The image of Crazy Horse began to take shape in time for an official dedication in 1998 at a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the project’s inception.

Mrs. Ziolkowski also expanded and developed the 1,000-acre site, which includes an American Indian history museum, a restaurant and the Indian University of North America, which works with the University of South Dakota to offer credits for college-bound high school students.

The site draws 1.2 million visitors annually, said memorial spokesman Mike Morgan, who confirmed Mrs. Ziolkowski’s death from cancer at a hospice in Rapid City, South Dakota

Stories about the couple noted Mrs. Ziolkowski’s low-key authority. She wore white moccasins, hair bands, simple dresses and smocks — a look that disguised her bourgeois New England roots.

Ruth Carolyn Ross was born June 26, 1926, in Hartford, Conn., and grew up in West Hartford, where her father was an insurance executive and noted amateur golfer.

Ruth once said that she met Korczak Ziolkowski, who was living blocks away, when she was 13 and heard that the movie and stage actor Richard Bennett was a guest in his home. She obtained the actor’s autograph and also became swept up in Ziolkowski’s efforts to raise money for a memorial he was building to honor a West Hartford native son, lexicographer Noah Webster Jr.

She recalled that Ziolkowski, then 30, scandalized the town with his habit of working stripped to the waist and on Sundays. He was a barrel-chested 6-foot-1, and in later years his shaggy whiskers and rustic wardrobe led to descriptions on the order of “Bunyanesque.”

After he returned from Army service in World War II, Ziolkowski asked Ruth to be one of his assistants and join his small caravan heading to South Dakota. They left early one morning in April 1947. Her parents were not overjoyed.

Korczak Ziolkowski was born in Boston and endured a hardscrabble early life before he began winning sculpting contests. He went to South Dakota in 1939 as an assistant to Gutzon Borglum, the eccentric visionary behind Mount Rushmore.

After Ziolkowski came to near-blows with Borglum’s son, the Polish American artist was persuaded by a Sioux leader, Henry Standing Bear, to build a competing monument. Standing Bear wrote to Ziolkowski, “We would like the white man to know the red men have great heroes also.”

Ziolkowski bought the mountain from the federal government, trading a parcel he owned elsewhere. He directed the dynamite blasts that initiated the work on June 3, 1948. Not long after, his first wife, a Boston socialite and concert violinist, filed for divorce, charging mental cruelty.

Korczak and Ruth wed on Thanksgiving Day, 1950. Over the years, they supported themselves running a dairy farm and selling gravel for road construction. Mrs. Ziolkowski also took care of her husband after heart attacks and severe work-related back injuries. She embraced the provincial life, once telling a reporter it had been 15 years since she had been anywhere beyond Rapid City.

Survivors include nine children, many of whom remain involved in the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation; 23 grandchildren; and 11 great-grandchildren. A daughter died in 2011.

The projected date of completion remains unclear, board officials said, because millions of tons of rock still need to be blasted away — carefully, so as not to destroy needed granite. Mrs. Ziolkowski will be buried at the base of the mountain, next to a tomb her husband carved for himself.

The project’s incremental pace confounded and fascinated many over the decades. Mrs. Ziolkowski said her life and her husband’s had not been, strictly speaking, about trying to whittle rock into art.

“He decided it would be well worth his life carving a mountain, not just as a memorial to the Indian people,” she told the Associated Press in 2006. “He felt by having the mountain carving, he could give back some pride. And he was a believer that if your pride is intact you can do anything in this world you want to do.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.