As the number of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder has soared, a nationwide effort is gaining ground to spread the word about the likelihood of their wandering off from a safe environment.

Of the over 500,000 children on the autism spectrum, about half are prone to wandering. This behavior has been linked to the deaths of dozens of children with autism since 2008. One such tragedy — involving a New York City boy found dead in a river three months after he walked away from school — has spurred the U.S. government to fund GPS tracking devices for children with autism spectrum disorders.

But while the effort to expand families’ access to tracking devices is a worthy one, it shouldn’t overshadow the lower-tech strategies for preventing and responding to wandering by children with autism: collaboration, education and sharing information. Though safety can be enhanced by technology, it shouldn’t depend on technology.

This year, the Justice Department agreed to cover the cost of GPS tracking devices for children with autism. Distribution will be managed by local law enforcement agencies. Sen. Chuck Schumer, who initiated the push for federal coverage, said he’ll continue to press for legislation to secure long-term federal funding for the devices.

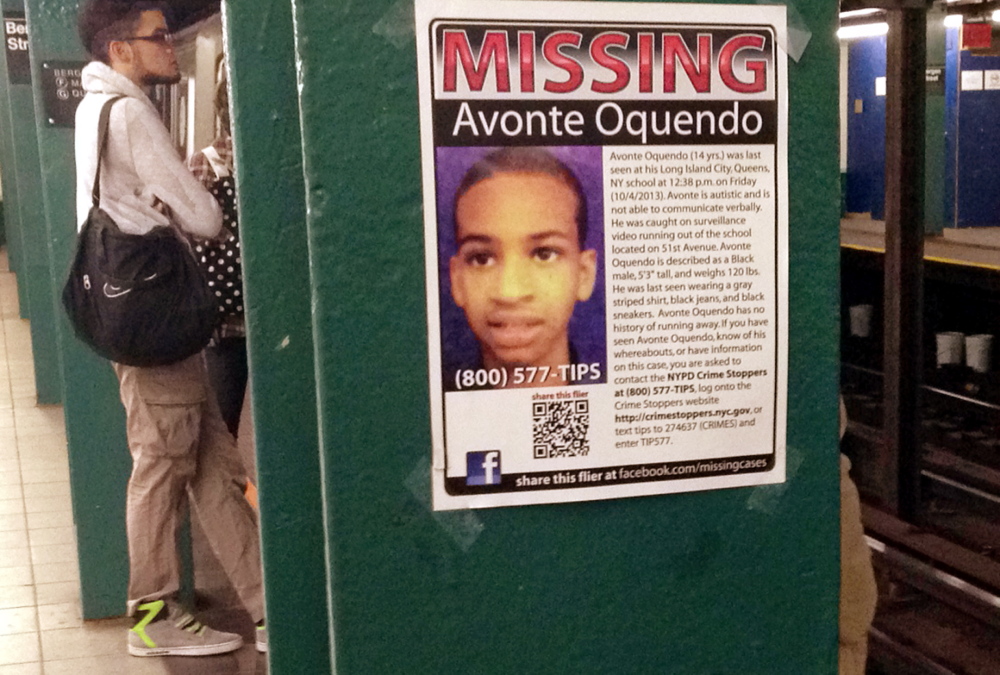

GPS might have saved Avonte Oquendo, a Queens boy who had a severe form of autism and couldn’t speak. It’s also highly probable, though, that stricter school safety protocols would have helped. Videotaped surveillance footage indicates that a security guard saw the 14-year-old leave the building last Oct. 4 but didn’t stop him.

And it’s far from clear whether tracking devices would have made a difference for Jaden Dremsa. The Waterboro 15-year-old’s body was recovered May 17, nine days after he told his family he was going for a walk; state officials concluded that he drowned in a nearby lake after hitting his head. But GPS units aren’t waterproof, and they’re not always reliable in wooded or rural areas. What’s more, some experts have said, wearing a tracking device might seem unnecessary and stigmatizing to young people like Jaden Dremsa, who had a high-functioning form of autism.

Maine’s autism community is pioneering efforts to educate families and the larger community about wandering. Through the Autism Society of Maine, federal probation officer Matt Brown — father of a boy with autism — has trained several thousand Maine law enforcement officials in searching for people with the disorder.

Brown also encourages parents to tell local police that they have a child with autism and offer specific information, like how their child might behave when approached. He’s hoping this data can be put into electronic form so it can be more easily shared in the field by officers from different agencies.

Making GPS units accessible to more families can’t hurt, but there are other ways to ensure the safety of children with autism, and the advent of electronic tracking devices should encourage more — not less — creative thinking on this issue, which is so urgent to so many families.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.