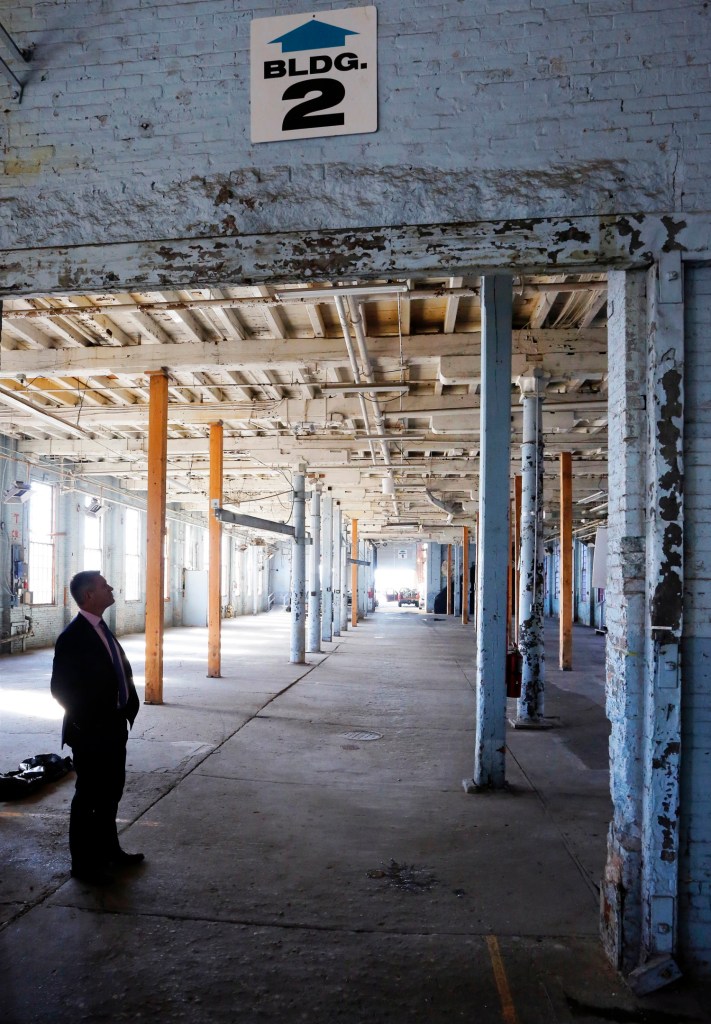

Jim Brady stood in the middle of a shadowy alleyway that, in many ways, epitomizes Portland’s decades-long transition from a gritty working town to a city where waterview condos sell for seven figures.

To his right was a cavernous empty building where Portland Co. workers once built locomotives and massive metal machinery. While the nearly 170-year-old building shows its age, Brady can envision a restored structure housing a thriving marketplace akin to Boston’s Faneuil Hall.

On his left were the crumbling facades of industrial structures built into Munjoy Hill that Brady said are likely too far gone to save. In their place, Brady pictures two- to three-story residential buildings – brick-faced but modern – overlooking Portland Harbor at the base of Portland’s hottest real market.

“It has so many attributes that make it wonderful but also make it challenging to deal with,” Brady, a developer, said last week of the former Portland Co. complex at 58 Fore St.

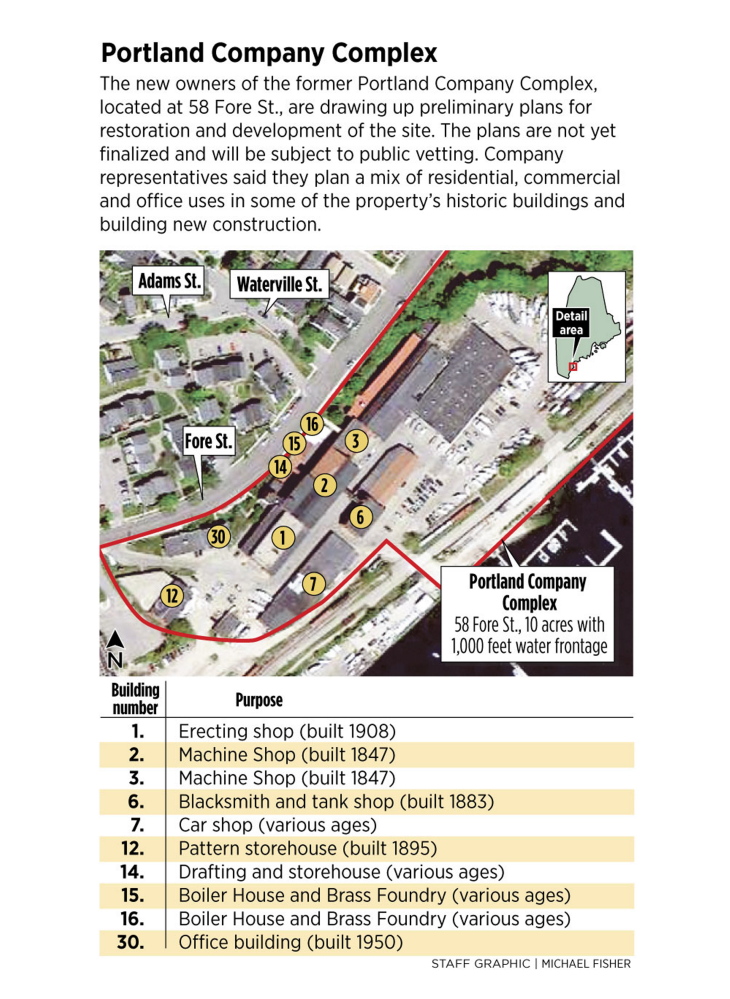

Brady and Casey Prentice – two business partners with the company CPB2 LLC, which purchased the Portland Co. site last year – shared some of their ideas for restoring and redeveloping the historic complex occupying 1,000 feet of waterfront adjacent to Portland’s downtown business district.

They stressed that the ideas are still preliminary because much depends on the outcome of a pending rezoning request, subsequent planning steps and market conditions. But any plans are guaranteed to draw close scrutiny from city planners and historic preservation groups who view the Portland Co. site as a key piece of the history of the city itself.

The vision the two men laid out was to retain the “historic core” of the complex, including:

• The two large “machine shop” buildings – Nos. 2 and 3 – dating to 1847 are where the Maine Boatbuilders Show and the Portland Flower Show are held annually.

• The “pattern storehouse,” or No. 12, which features the large black-and-white painted “Portland Co.” logo visible from Fore Street and the waterfront along Thames Street.

• Building No. 6, the former blacksmith/tank shop now housing the “Room with a View” banquet room and connecting to the machine shop via an elevated walkway.

• The No. 24 tower “vault” across from the two large machine shops.

Other buildings they deem of lesser historic value could be demolished, including the No. 1 “erecting shop,” which is the first industrial building visitors encounter while driving into the complex, the No. 7 “car shop” and the modern office building dubbed No. 30.

In the case of the low-slung “car shop,” CPB2 currently envisions removing that building in order to create a roughly one-acre public plaza that opens onto the harbor and connects to the Eastern Promenade Trail, which would also be re-routed to run along the water line. Prentice and Brady said they hope to use hard-stone landscaping to connect Fore Street and Munjoy Hill to the waterfront.

The railroad tracks currently used by the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Co. would remain on site, although they may be relocated closer to the water.

“It was never our intention to come in here with a bulldozer and tear everything down,” said Brady, who is currently converting the former Portland Press Herald building on Congress Street into a boutique hotel. “We think there are great attributes to the historic buildings. But we also don’t think every building has to be saved.”

A historical and architectural analysis commissioned by the city of Portland called the complex “one of the most historically important sites in the city of Portland.”

The Portland Co. began production at the Fore Street site in 1847 and ceased operations in 1982. During that period, the company produced more than 600 locomotives, hundreds more ship engines, navigation buoys, lighthouse components and countless pieces of heavy machinery for the textile and paper industries. The complex was one of the largest employers in the city and actually influenced the shape and road layout of the Portland waterfront.

The study by Sutherland Conservation and Consulting states that the Portland Co. complex has national historic significance because it appears to be the country’s first and only remaining site where all aspects of manufacturing railroad equipment – from the foundry to the machine and car shops – were housed in a single complex. While the study authors said some of the more modern buildings could be removed to free up space for new development, they added: “The removal of any of the historic buildings existing in the complex will diminish the ability of the complex to demonstrate the historic manufacturing process of the Portland Company.”

Greater Portland Landmarks, a nonprofit organization that works on historic preservation, has requested that the Portland Co. property be designated as a historic district. Such a designation would subject any development plans as well as changes to historic buildings to greater scrutiny.

Last week, members of a City Council committee recommended handling CPB2’s rezoning request before dealing with the historic district designation.

There are more than a dozen buildings within the Portland Co. complex, many of which are still in use. The property’s previous owner, Phineas Sprague Jr., still operates his boat repair and service facility out of the buildings as he builds a new boatyard on the western end of Commercial Street. Other spaces are filled by artists, craftsmen as well as The Portland Forge, a forge operated in the same location as Portland Co.’s original location and using the same blacksmithing techniques used in the mid-1800s.

The condition of the buildings varies widely, although Brady noted that a firm hired by CPB2 to study the structural integrity of the buildings rated only one as being in “fair” condition. Most, he said, were rated as poor or worse and would need extensive, expensive renovations to bring them up to code, if they were salvageable at all.

The two large machine shops feature what appear to be the original vertical beams, although support poles and beams have been added over the decades to support the ceiling. The walls are bare brick with no insulation, and one of the buildings alone costs an estimated $6,000 a month to heat during winter, Prentice said.

The uppermost level, visible by dormers added later, is cluttered with old equipment and assorted junk. One room, unlit and spooky even during the day, still contains Portland Co. register books from the early 1900s.

Hilary Bassett, executive director of Greater Portland Landmarks, said her organization is “very excited” about the potential reuse of the historic buildings as well as the opportunities for integrating contemporary architecture on the site. She believes the site, if done right, could create a property that is “uniquely Portland.” Bassett said members of Greater Portland Landmarks look forward to meeting with Prentice and Brady in the coming weeks to hear their latest plans and discuss options for the site.

“We still have some concerns about how many of the historic buildings will be retained,” Bassett said. “We also feel there are some opportunities to integrate modern buildings with historic buildings … in a way that couldn’t be anywhere than Portland.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.