Plans to build a major wind project in the western Maine mountains could again test the legal separation between power generators and distribution utilities, a bedrock rule in deregulation of the state’s electric industry 15 years ago.

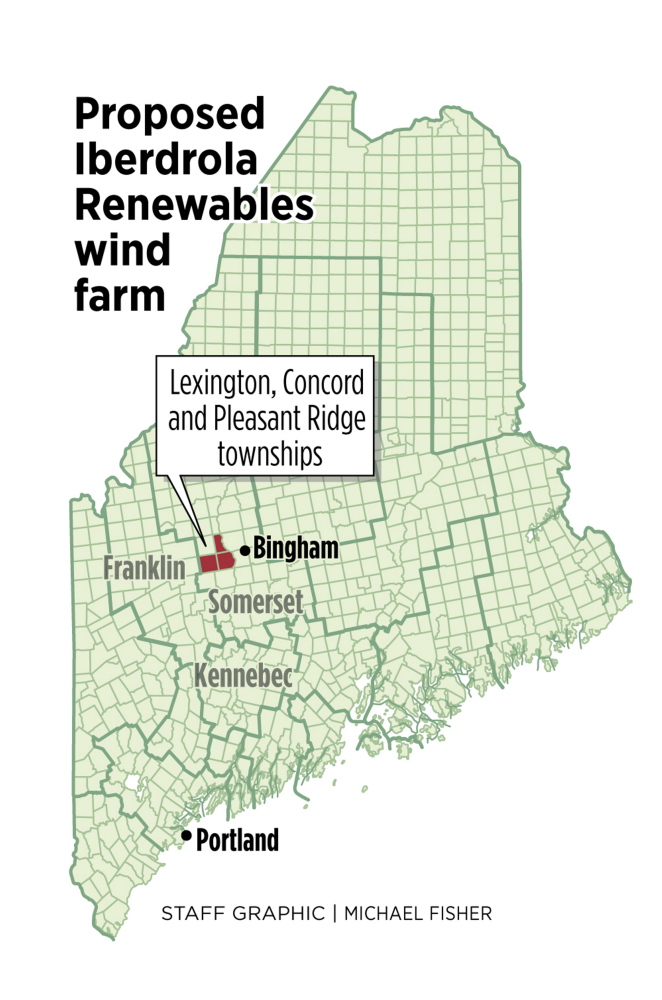

The project is being proposed by Iberdrola Renewables, a subsidiary of Central Maine Power’s parent company, the Spanish energy giant Iberdrola S.A. Called West Range Wind, the project would be located in Concord, Lexington and Pleasant Ridge townships, between New Portland and Bingham.

Although the layout is still being refined, plans call for up to 33 turbines reaching 500 feet high. The wind farm would have a capacity of 100 megawatts, generating enough power for 36,000 homes, based on average demand and the developer’s output estimates.

Beyond its scale, West Range Wind will be a significant test for Iberdrola Renewables, the second-largest wind operator in the United States. It is evaluating other sites in Maine and has proposed a second, large-scale wind project in Washington County, where it has leased thousands of acres of land in Trescott and Whiting.

But Iberdrola Renewables must first clear a legal hurdle meant to protect electric customers from self-dealing by affiliated power companies. Next week, an influential interest group concerned about whether the project could receive favorable treatment from CMP plans to intervene in the approval process now getting underway at the Maine Public Utilities Commission.

At issue is the relationship between power generators, such as Iberdrola Renewables, and distribution utilities that connect them to the grid, such as CMP. A key part of the state’s deregulation law created competition among generators by eliminating common ownership.

That policy had been challenged in recent years, when Boston-based First Wind and Emera, the Canadian energy company that owns utilities in eastern and northern Maine, formed a joint venture in 2012. The PUC approved the deal with several conditions, but opponents who saw the opportunity for favoritism between the two fought the approval at the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. They won, throwing the case back to the PUC. Again the PUC gave its approval and again opponents mounted an appeal, which is ongoing.

But in November, a large solar energy company, SunEdison, announced that it was buying First Wind. That dissolved the First Wind-Emera joint venture. As a practical matter, it also resolved any issues about their relationship and the deregulation law.

“But it doesn’t change the policy question and it doesn’t tell us what it means for the future,” said Andrew Landry, a lawyer who represents the Industrial Energy Consumer Group.

The group, made up of paper mills and other large power users, is preparing to intervene in the pending PUC case to see whether the CMP-Iberdrola Renewables link raises similar issues as First Wind-Emera.

For example, Landry said: Would CMP have an incentive to build a new transmission line to help move power from projects owned by a sister company?

That’s not likely, said Paul Copleman, a spokesman for Iberdrola Renewables. The western Maine project isn’t being proposed as a joint venture, as was First Wind and Emera.

“CMP has to treat us like any other developer in this process,” he said. “We’re two different companies with a set of rules about how we interact and do business.”

Copleman noted that Iberdrola is in the early stages of developing West Range Wind. It’s still seeking a power-purchase agreement to sell the output. It may submit an application next year to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, but it could be a few years before any electricity is being produced.

Some of the questions that people have about the project will be discussed next week, when the PUC staff has an initial meeting with the parties, said Jeremy Payne, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association. In his view, the agreement that CMP seeks to connect the project to the grid doesn’t present the conflicts that some opponents envision.

“This is pretty standard,” Payne said. “Utilities do this for generators anyway.”

The legal wrangling isn’t the focus of local residents who have been fighting wind projects in the unorganized townships. They just don’t want to see and hear giant turbine blades spinning on the forested ridges near where they live.

Karen Bessey Pease, who lives in Lexington Township, said the majority of residents there have signed petitions opposing the project.

“This is a quiet rural area that will be forever changed in a big way,” she said. “We are absolutely opposed.”

It’s way too early to guess how the PUC will rule on this case, but it’s noteworthy that two of the three deciders will change.

The commission’s chairman, Tom Welch, is retiring this week and Gov. Paul LePage has yet to nominate a replacement. The term of a second commissioner, David Littell, ends in March.

In the First Wind-Emera case, both Welch and Littell voted in July for approval of the joint venture. The lone dissenting vote was Mark Vannoy, a LePage appointee.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.