Tony Hoagland understands why you don’t like poetry – or why you think you don’t. It has to do with the way generations of Americans were introduced to poetry in school. It was boring and tedious and emphasized memorizing lines instead of figuring out what they meant.

It’s only gotten worse, Hoagland said in a phone call from Texas. Education’s results-oriented fixation on the Common Core curriculum has pushed poetry off the table. “People make the argument that if we teach math skills or science skills or computer skills, it will increase the lifetime earning potential of students by X amount,” the poet said.

“The problem is, when you buy into that equation, everything else gets left out. We should not have to argue that creativity improves the quality of life, but in this era we are forced to argue things that are incredibly obvious. The joy of creativity should be part of every day. It’s part of what makes us human. It improves everything.”

Hoagland, a past Guggenheim Fellow, will make a stand for poetry and humanity April 16 in Portland as the inaugural speaker in a new visiting poets series, which organizers hope will continue the populist poetry agenda of Maine Poet Laureate Wesley McNair. McNair, a quiet, lanky man from Mercer, is in the final year of a five-year term as poet laureate. He’s taken advantage of the soapbox that comes with the position, making it his goal to remove poetry from its ivy pedestal and return it to the daily lives of Mainers.

McNair’s success will be measured with time, but there’s no question that Hoagland comes to Maine during a time of renewed interest in and acceptance of poetry. In part because of its literary heritage and also because of the efforts of McNair and others, Maine is a place where poetry flourishes. “What I hope is that people are now more aware of poetry’s presence in Maine and of the excellence of Maine poetry,” McNair said. “And I hope that poetry has come to matter just a little more to people outside the poetry beltway.”

On April 7, McNair will host Poetry Day at the Capitol in Augusta. Keeping with the “Poetry for the People” theme of his term, McNair moved the event from the Blaine House, where it was invitation-only, to the Hall of Flags, where it is free and open to everyone. As part of Poetry Day, McNair is inviting everyday Mainers to read their favorite poem. Among the readers will be a Sawn’s Island lobsterman.

APRIL IS National Poetry Month, a time of mixed blessings for poets. The attention the month brings is nice, but poetry isn’t synonymous with springtime bliss, said Joshua Bodwell, executive director of the Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance. Poets worry the attention of April comes at a cost. “We’re here the other 11 months of the year.”

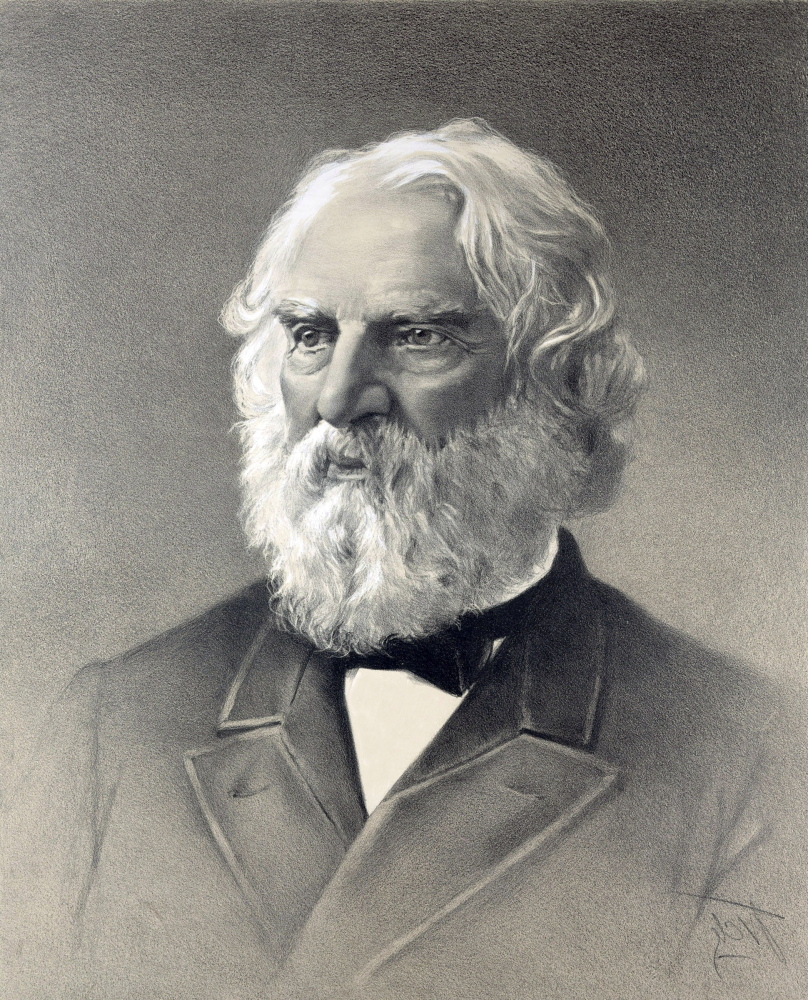

Maine is home to many poets who publish nationally, including most famously Richard Blanco of Bethel, who wrote and delivered a poem for President Obama’s second inauguration in January 2013. Blanco filled Merrill Auditorium in Portland when he read a few weeks later, exhibiting celebrity star power among poets not seen in these parts since native son Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Maine also is home to many poetry presses – small niche publishers motivated by passion for language and hopeful for nothing more than breaking even. Communities from Portland to Belfast to Weld have municipal poet laureates, and Maine has a rich poetic legacy that extends beyond Longfellow’s prodigious reach. Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote her first poems in Camden, and Gardiner’s Edwin Arlington Robinson has the distinction of winning three Pulitzer Prizes.

It’s not just a dusty history, Bodwell said. Every generation of Maine readers since can claim a poet of distinction.

Given all that, why does poetry remain a fringe art form? Why do poets attract friends and colleagues – as McNair puts it, “all the usual suspects” – to their readings, but not necessarily a general audience, with Richard Blanco being the exception?

HOAGLAND, WHO spent many years in Maine teaching at Colby College and the University of Maine at Farmington, thinks it comes back to how we teach poetry in schools. He thinks generations of Americans are “traumatized” from their experience with poetry when they were kids. By instinct, they find poetry intimidating and inaccessible because it conjures the worst of the leftover nightmares from school: standing in class, mouth agape with no words on your lips and none coming.

Standardized testing aside, Hoagland likes to teach poetry that is fun and full of humor and joy. He will promote contemporary American poems when he comes to Portland “that are full of the world, full of images and full of metaphors that are light on their feet.”

As he does in his classroom, he will appeal to the integrity of the language and the satisfaction of a well-constructed sentence.

Our language has been broken by hucksters, he said. Twitter has reduced acceptable communication to run-on sentences and fragments.

It’s time, Hoagland said, to “take the American language out for a run. That’s worth doing.” Next time you go to dinner at a friend’s house, bring the gift of a poem in addition to a bottle of wine, he said. “It’s a way of inseminating contemporary social life and culture with this thing called poetry. That’s a civilized life,” he said.

ALICE PERSONS is among the lucky ones. She began writing poetry in grade school and always seemed to find “saint-like teachers” who encouraged her interest in language. These days, the Westbrook woman publishes small books of poetry under the Moon Pie Press banner. She’s been at it 12 years and considers her publishing career successful because she’s helped many writers publish their poems for the first time.

It’s never been about the money, she said. “The need is there. Zillions of talented poets have books and no place to publish them. It seems I will never run out of manuscripts.”

For each one she publishes, she turns down 10. Persons fits publishing in among her other jobs, one of which is teaching. She agrees with Hoagland. Poetry’s biggest obstacle is fear: People fear poetry because they don’t understand it.

Emily Vail sees that fear or something like it on the faces of students and teachers at Mt. Ararat High School in Topsham. For six years, Vail has tried to persuade her English department colleagues to rally behind the statewide Poetry Out Loud recitation competition for Maine high school students. For the most part, her prodding hasn’t worked. She’s enlisted an enthusiastic teacher or two, but sometimes feels she’s on a poetry island.

“It has bedeviled me,” Vail said. “I think maybe some teachers are uncomfortable with poetry themselves. I think for some of them, poetry was ruined by their experience with poetry as kids.”

THIS YEAR, Rose Horowitz is among Vail’s students. Horowitz fears no poem.

The 16-year-old junior from Harpswell won the state Poetry Out Loud competition and will represent Maine in Washington, D.C., at the end of April. She will recite three poems: “Lovers’ Infiniteness” by John Donne, “Discrimination” by Kenneth Rexroth and “Entirely” by Louis MacNeice. But she doesn’t merely recite them. Horowitz performs them, infusing her language with drama that matches the lyrical complexity of the written words.

Horowitz said her closest friends understand her love of poetry. But most of her peers don’t.

“When I say I recite poetry, I think they picture someone older saying a poem very slowly in a monotone. But that’s not what Poetry Out Loud is about.”

Poetry Out Loud is about finding the emotional core of a poem and expressing it physically and orally.

Poetry, she said, “is like the world without physics. There are no rules. You can express yourself however you want.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.