FOX LAKE, Ill. — He gave teenagers their own keys and 24-hour access to the police department. He forged the police chief’s signature to obtain surplus military equipment. He often refused to wear his police uniform on duty in favor of camouflage fatigues. And he spent most of his workday on a police-sponsored youth program that he was supposed to run on his own time.

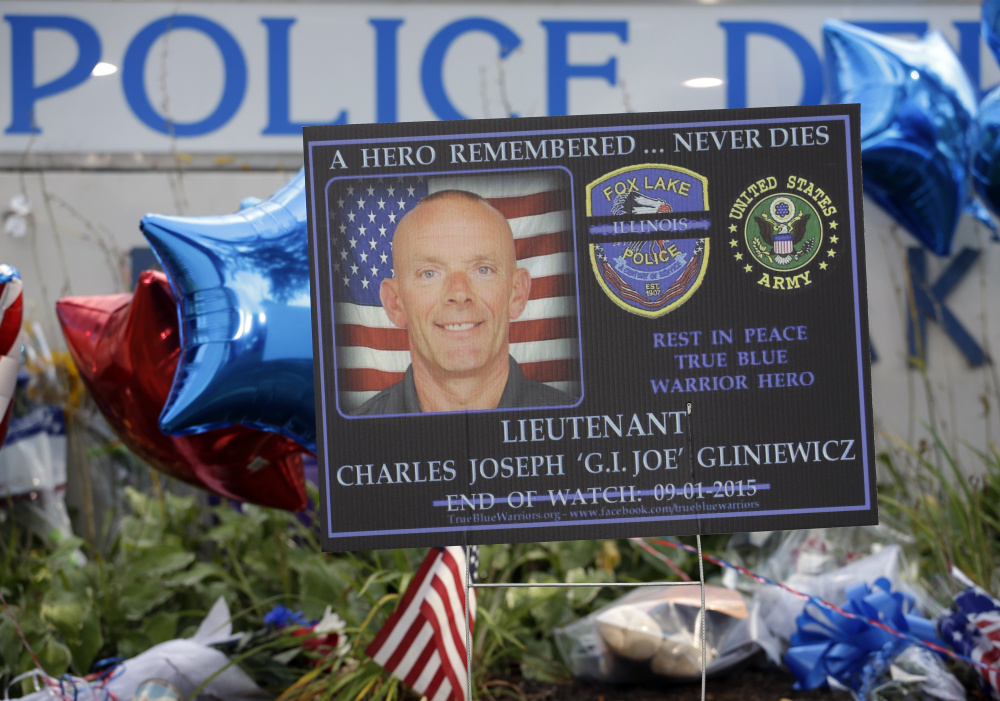

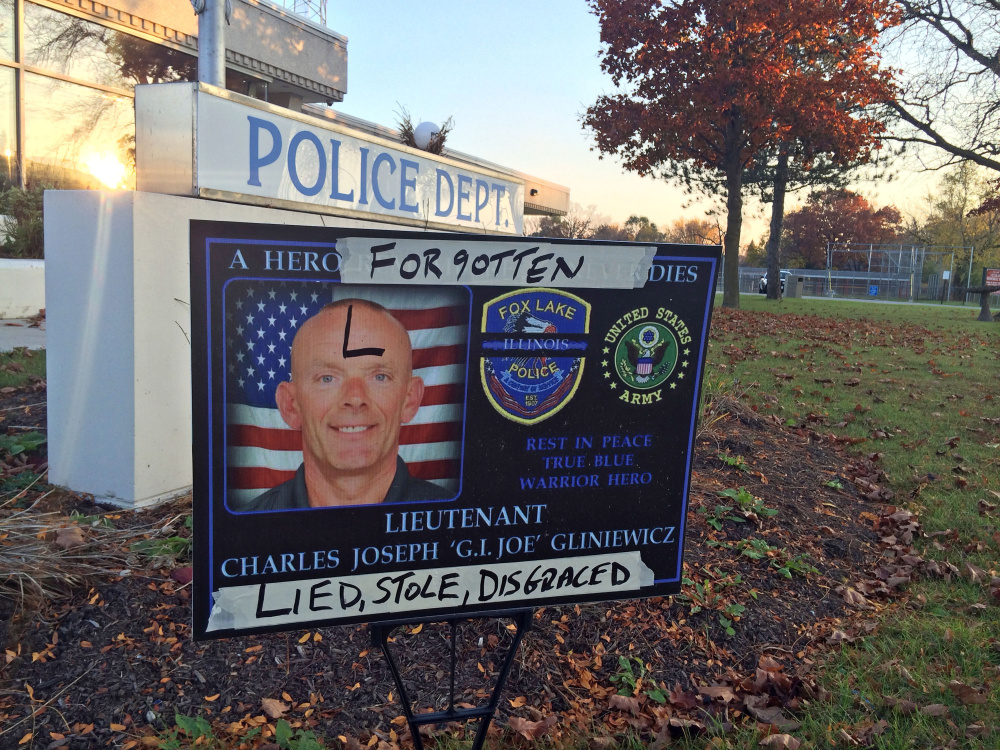

Lt. Charles Joseph Gliniewicz, the small-town Illinois cop who staged his own death to look like a homicide after realizing he would be exposed as a thief, was able to run roughshod in the department for years because officials exerted little control over him or the award-winning youth program that made him a popular figure known as “G.I. Joe” in the bedroom community of 10,000 people 50 miles north of Chicago.

They glossed over serious transgressions – including allegations of sexual harassment and intimidating subordinates – rather than fire the public face of the police department, according to internal documents and interviews with officials.

Now, the investigation of Gliniewicz’s death on Sept. 1, which touched off a massive, weekslong manhunt for killers who didn’t exist, is bringing to light not only the officer’s abuses but the official acquiescence that nurtured his behavior.

“Joe Gliniewicz was allowed to do whatever Joe Gliniewicz wanted,” said Michael Keller, a Lake County Sheriff’s detective who was brought in to run the department after Gliniewicz took his own life in an apparent attempt to cover up his theft of thousands of dollars. “He should have been fired a long time ago.”

A reconstruction of Gliniewicz’s 30-year career in the department shows a series of problems followed by second and third chances, and eventually promotions to positions of more authority.

When a sheriff’s deputy found Gliniewicz passed out in his truck after drinking, his foot on the gas, a Fox Lake officer took him home and had the truck towed. Gliniewicz, who reported the truck stolen, was not punished.

When a female officer complained in 2001 that she was pressured for sex in exchange for him protecting her job, the police chief at the time gave Gliniewicz six, 5-day suspensions to avoid informing the village police commission, which had to approve suspensions longer than five days, according to court records.

The woman told The Associated Press that Gliniewicz got off easy because “he was the one that ran the whole Explorer program. He put out the news releases and talked to the reporters.”

Keller agreed: “He was put on a pedestal,” even though his fellow officers distrusted him – so much so that none attended a party earlier this year for Gliniewicz’s 30th year on the force, Keller said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.