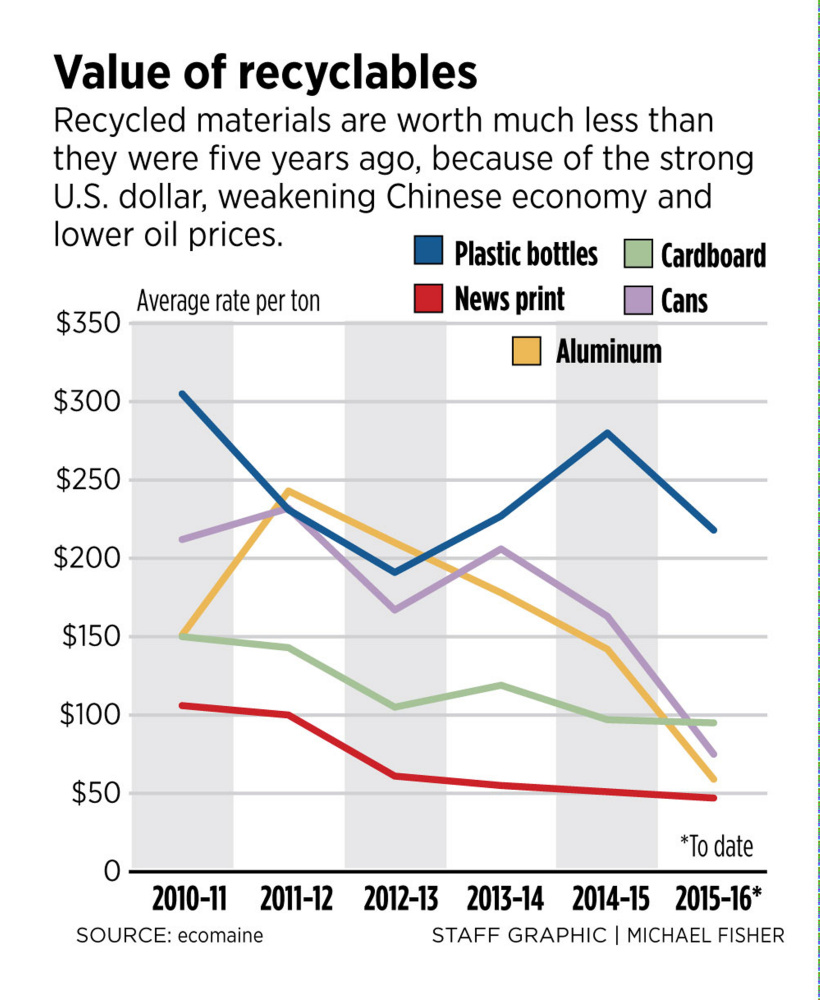

Just over a year ago, the metal soup and sauce cans that many Mainers diligently wash and toss in recycling bins were worth $184 a ton at ecomaine, the nonprofit agency that handles solid waste for Portland and four dozen other communities. At the start of 2016, the value of those cans had fallen by two-thirds, to $63.

A grade of plastic used for salad dressing and peanut butter containers fetched $240 a ton last winter. This past January, ecomaine could get only $160 a ton, one-third less.

The depressed value of recycled materials worldwide means that ecomaine is earning less money. The shortfall is contributing to a revenue loss totaling $3 million, compared to three years ago. Expectations that recycling values will remain low and that ecomaine will have to make up for the lost revenue are raising prospects that Greater Portland residents may begin paying more to dispose of their waste next year.

To help cover the current cost of operations, ecomaine two years ago began charging haulers $35 a ton when they bring recycled materials to its waste-to-energy plant. Charging money to recycle has become a national trend in the last couple of years, although ecomaine is using cash reserves to temporarily insulate the communities that own the waste-to-energy plant on the outskirts of Portland.

Of course, it’s residents who ultimately will pay the bill, through their taxes or through what their trash collector charges. Despite this new normal, ecomaine is encouraging people to keep recycling. It processed a record 43,667 tons of recycled material last fiscal year, aided by an outreach campaign around sustainability conducted online, through social media and traditional outlets.

This seeming contradiction is rooted in the state’s waste management hierarchy. In sum, it’s better for taxpayers – and for the planet – to reduce, reuse, recycle and compost than to burn or landfill. It’s expensive to site and build new waste disposal facilities, and no one wants to live next to them.

But the idea of paying to recycle might take some getting used to, according to George MacDonald, who directs the sustainability division at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. People may be surprised, he said, because they’ve been conditioned to think that if they do their part, government and the markets will take things from there. They assume the money made from recycling more than covers the cost of collecting the material.

“As long as commodity markets remain depressed, we are going to see that approach,” MacDonald said of paying to recycle. “It costs money to run a truck around and pick up materials and process them. And if the final value isn’t there, a company has to figure out how to support the services.”

‘STARS HAVE ALIGNED IN A NEGATIVE WAY’

Global events are driving the sharp decline in recycling values. A major factor is the weakened economy in China, which for years bought mountains of used metal, plastic and paper to create consumer goods. China’s slowdown has coincided with a strong American dollar, which makes exporting materials more expensive. On top of that, the plunge in oil prices has dulled the incentive to recycle plastic.

But ecomaine has a further challenge.

The waste-to-energy plant burns 180,000 tons of trash a year, generating enough power to serve 14,000 homes. But its latest wholesale electricity contract is down 10 percent from last year, due to the falling cost of natural gas. That will cut overall power revenue by $425,000. Electricity prices look like they’ll stay low for a while, so there’s little hope of more-favorable contracts.

This winter, ecomaine sought help in the Legislature through a proposed law change that would have increased the rate subsidy for renewable power from waste-to-energy plants. The impact on electricity customers would have been tiny, maybe a dime a month, according to ecomaine. But the proposal has failed to gain support.

“The stars have aligned in a negative way,” said Kevin Roche, ecomaine’s general manager.

The latest financial statements compiled by Roche lay out the trend. Year-to-date operating revenues from January 2013 to 2016 show the total falling from $14.3 million three years ago to $11.3 million this past January, a loss of $3 million.

Contributing to the shortfall is the drop in recycling value, from a peak of $2.2 million in 2014 to $1.4 million last January. Electricity sales are down from $3.4 million last year to $2.7 million in January.

On top of that, waste disposal costs, known as tipping fees, declined in 2014, after ecomaine cut the charge per ton for owner communities by 20 percent. Tipping fees now bring in a total of around $7 million a year.

This give-back to owner communities was complemented by halting an annual assessment set years ago to secure debt financing. As with the tipping fee, the zero assessment was a welcome windfall for cities and towns, but it drained $1 million from the plant in the last fiscal year.

ADAPTING TO ‘THE NEW NORMAL’

Despite all this, ecomaine and its owners are in an enviable position. The plant has paid off all its debt. And it has strong cash reserves, roughly $27 million.

But to be conservative, ecomaine needs to consider raising the tipping fee next year, Roche said, probably 3 percent or so. He’ll present his recommendations later this month to the agency’s board and expects the finance committee to weigh in this fall as it updates the five-year plan.

“We have $27 million in reserves, so our balance sheet is able to withstand a downturn in the market,” Roche said. “But if this is the new normal, that’s a problem.”

At least one industry leader sees low commodity prices as a new normal.

Casella Waste Systems operates throughout Maine, with trash pickup, recycling and composting. It also runs the state-owned Juniper Ridge landfill in Old Town, with plans to expand it.

Unlike ecomaine, Casella is a for-profit company. In a financial report last year, the company’s chairman and chief executive said he saw the downturn in commodity prices as an international and long-term condition.

“We have taken action,” John Casella said, “to begin to reshape our recycling business model through increased tipping fees at our recycling facilities and pricing increases to our collection customers to reflect the dramatically lower recycling commodity values.”

Casella is doing this through what it calls a “Sustainability/Recycling Adjustment Fee.” Joe Fusco, a Casella spokesman, said the fee varies and adds up to a few percentage points on a customer bill. In Greater Portland, for instance, a home customer who pays $30.88 a month for trash pickup is paying a recycling fee of $1.64.

“The challenge is, how do we over the long run structure the cost of recycling, so it becomes economically sustainable?” he asked.

At ecomaine, the $35-a-ton recycling fee is half the cost of waste disposal. That’s a good compromise, according to Jim Gailey, South Portland’s city manager and ecomaine’s chairman.

“If we didn’t recycle,” he said, “it would all be burned and turned into ash, which would have to go to the ash landfill.”

Gailey said the value of recycling goes beyond dollars, because there’s strong public support for taking reusable materials out of the waste stream.

“The last thing I want to do is discourage people from recycling,” Gailey said.

But it took many years to gain that public support and change behavior. Part of the evolution, according to Travis Wagner, a professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Southern Maine, is that people think recycling is free. Few people would be agreeable to paying an upfront fee to recycle something that has no apparent value, he said.

“I think there would be a tremendous outcry and backlash,” he said.

Only a small subset of residents, whom Wagner refers to as “true greens,” will knowingly pay to recycle. That model is being tested with organics, which make up nearly 40 percent of the home waste stream. Uneaten salad greens and coffee grounds are heavy and don’t burn, but make good compost. Start-up businesses such as Garbage to Garden in Portland collect buckets of household organics each week and compost the contents at a farm in Gorham.

Garbage to Garden charges $14 a month for the service, or $154 a year prepaid.

Correction: This story was updated at 1:44 p.m. Monday, March 14 to correct the cost of Garbage to Garden’s services.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.