AUGUSTA — Hayden Stratton knelt beside Bond Brook Monday to watch the half-dozen tiny Atlantic salmon alevin he had just carefully poured into the water from a plastic cup begin their new life in the wild.

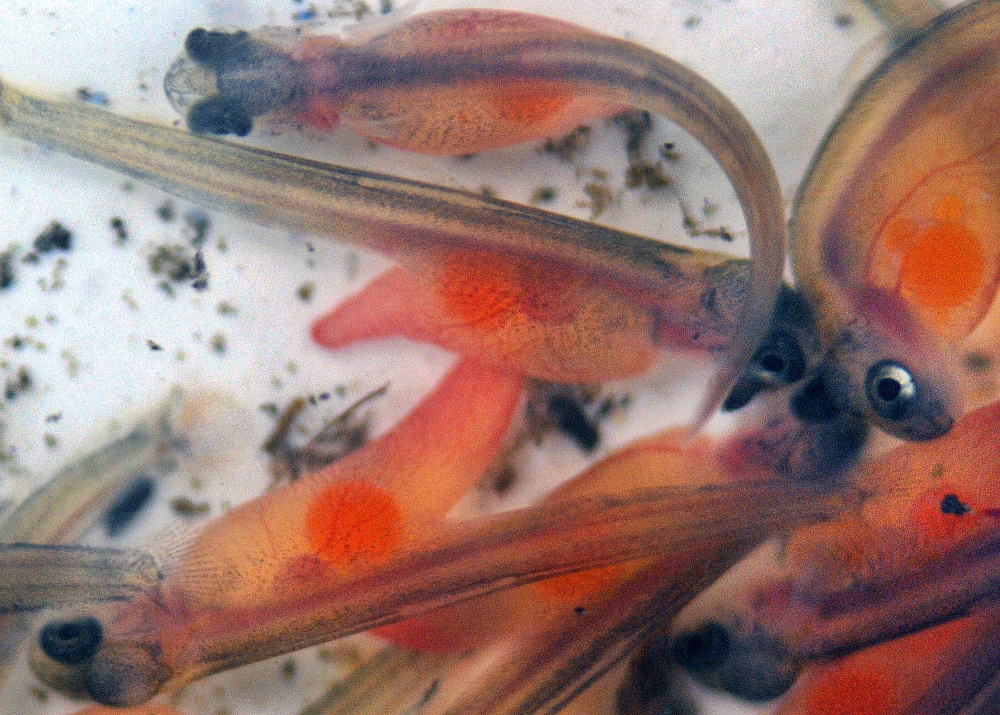

“They didn’t go too far,” Stratton said of the small visible salmon in orange yolk sacks. “They’re just chilling, dude.”

The fish will chill in Bond Brook for about two years, struggling for life as they learn to eat and hide from predators. If successful in those two things, they will grow to reach their fry stage, then parr stage, and then smolt stage before slowly making their way out to sea.

They’ll spend about a year heading down the Kennebec River, acclimating to the changing conditions along the way, said Peter Kallin, of Rome, president of the Maine Lakes Society. Kallin accompanied about 35 students from Messalonskee High School in Oakland as part of teacher Colin Hickey’s “Topics in Non-Fiction: Hunting and Fishing” class field trip. Each student placed some of the roughly half-inch long, endangered Atlantic salmon in the brook in hopes of helping restore their population.

Kallin said the fish came as eggs from the federal Green Lake National Fish Hatchery, part of a group of some 6,000 eggs Maine conservation groups will place in partnership with schools to help restoration efforts. He said their federal permits specify how many fish they can release and where.

He said the return of massive alewife runs in Maine rivers are good for Atlantic salmon, as well. He said the millions of alewives provide cover for the much smaller population of salmon and food for predators that might otherwise nab salmon for a meal.

Stratton, a sophomore from Sidney, is a frequent fisherman and said he appreciated the lessons Kallin shared about salmon.

“I enjoy the class, I hunt and fish, I’m always outside,” he said. “I like knowing about the fish I’m catching.”

Once back in school, the students will be expected to write their own newspaper articles about what they saw, heard and learned (Hickey is a former reporter for the Morning Sentinel in Waterville). The class is part of the English program at the school, but Monday’s lesson clearly involved a lot of hands-on science lessons about the life cycle of salmon.

That was fine with Belgrade senior Kyle McFarland, who said he was involved in a similar project back when he was in elementary school.

“Hands-on, you learn more and remember more,” he said of getting out of the classroom on a rainy Monday.

Matthew Leahey, education and outreach coordinator for the Belgrade Regional Conservation Alliance, a conservation group focused on the Belgrade Lakes watershed, said he works with several classes in Oakland-based Regional School Unit 18. He said these types of programs are valuable in making subjects such as English and science more relevant and interesting to students.

“It’s about making those connections. It makes it more meaningful, more relevant in their lives,” Leahey said. “Each student got to take some salmon and put them in (the brook) and be part of doing science.”

Kallin said the odds are slim any one of the 200 salmon they released Monday will survive the six years or so that’s necessary for the fish to swim back up the Kennebec River and Bond Brook to spawn. That process involves swimming some 2,000 miles to the Greenland Sea, between Greenland and Iceland, before returning.

He told students two adult salmon have around 3,400 eggs, but odds are only two of those eggs will grow into salmon that will complete the life cycle to spawn themselves.

“Their entire lives, something is trying to eat them. They’re very tasty,” Kallin said. “It’s not an easy life.”

Logan Parker, community engagement coordinator for the Maine Lakes Resource Center in Belgrade, played parent to a small cooler full of 200 salmon, slowly adding cupfuls of Bond Brook water to the cooler, giving time for the fish to acclimate to the temperature of their soon-to-be new home.

When the fish were ready to be released, each student grabbed a cup, reported how many fish were in it to Parker so he could record it, and then went down to deposit them into the brook. Some of the fish got swept downstream in the current, while others huddled in the slower water along the bank amid rocks and fallen branches.

Keith Edwards can be contacted at 621-5647 or at:

kedwards@centralmaine.com

Twitter: kedwardskj

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.