EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second in a two-part series on Maine water. Read part 1: Poland Spring reaches high water mark

HARRISON — The label on Summit Spring’s bottled water from Maine, priced at $46.57 for a 50-ounce case on Amazon, practically screams the word: RAW.

The more demure text below (“Pure Natural Untouched”) doesn’t include an explanation of what “raw” water is, nor why it costs so much.

For that, it’s best to go to the source itself in Harrison, where Summit Spring’s owner Bryan Pullen hovers protectively over both the past and future of his prize, a hilltop spring that has been a commercial operation on and off for over a century. Pullen, a pilot who makes his living flying for American Airlines, entered the bottled spring water market in 2003 and has been working with mixed success to build his spring’s boutique brand ever since.

His pitch is that Summit Spring’s product is true spring water, bottled as it comes out of the ground – “raw” because it isn’t treated, true spring because no pumping is involved – and produced in what constitutes tiny batches, especially compared to its much better-known Maine neighbor in the bottled-water business, Nestle-owned Poland Spring.

His business, Pullen claims, is also far more in tune with sustainability, an issue that dogs the bottled-water industry. Even as bottled water is poised to surpass carbonated beverages as the most popular beverage in America, likely later this summer, environmental groups and citizens groups decry it as wasteful, particularly in its packaging, as well as a questionable use of the groundwater resource.

“Nobody is more sustainable than us,” Pullen said. “We’re only taking Mother Nature’s overflow.”

If owner enthusiasm were the primary means to achieve business success, Summit Spring would already be the best-selling boutique spring water in the land.

“He’s vociferous,” said Daniel Vitalis, who co-founded a website called Find a Spring that keeps track of public springs. He connected with Pullen about eight years ago and the two of them, with their shared interest in water, hit it off. “He’s boisterous. And he’s a teddy bear. When it comes to water, and when it comes to that spring in particular, it is like he is a bear and that’s his cubs.”

Pullen radiated that excitement on a recent tour, issuing an invitation to climb into his pickup truck where he immediately pulled out a binder to show off his Summit Spring ephemera. He’s got multiple reproductions of vintage photographs of the long-gone Summit Springs Hotel, which had 55 rooms, three stories, a wrap-around deck on the second floor and amenities that included a nine-hole golf course.

He backed up the pickup and repositioned it. “See that?” Pullen said, pointing to an undistinguished lump of rock with plants growing out of it. “That’s the remains of the chimney.”

Names tumble out of him. Nathaniel Burnham (“Buried right there”) was the first Anglo-Saxon steward of the spring – that’s Pullen’s phrase, and he considers himself its fifth steward. Francis Whitman, who traded his farm in Norway with Burnham’s for the Summit Spring location, was the first to ascribe medicinal values to the waters and start selling it. Whitman left in 1888, the year the Summit Springs Hotel opened (one timeline places construction in 1884).

The hotel, not to be confused with the Summit Spring Hotel in South Poland, was advertised in the Boston Evening Transcript in July 1889 as home to “the celebrated Summit Mineral Springs, whose waters have won so wide a reputation for the cure of kidney and dyspeptic troubles, nervous prostration, insomnia, etc.” Visitors drank it and bathed in it.

Finally, Pullen drives the car down to the springhouse, built by L. Franklin van Zelm, who bought the hotel in the 1930s and lived there with his family for some years, treating it as a manor rather than a hotel. “The famous cartoonist,” as Pullen calls him, Van Zelm had two strips that ran regularly in the Christian Science Monitor.

‘LIKE A LIVING CREATURE’

“There is a lot of energy in this building,” Pullen said as he unlocked the stone and brown-shingled springhouse. A sweet, simple building, it has views out over the green hills of nearby Paris and Norway. The entryway is lined with old Summit Spring bottles – like one labeled “Natural Alkaline Water” from the mid-20th century, long before Pullen acquired the land and started calling it raw. A metal cover shields the original collecting pool, and Pullen unlatches and peels it back reverentially.

“It’s like a living creature,” Pullen said.

The water below is 3 feet deep, but so clear it looks half that. In the corner, the sand moves as the water bubbles up and spreads into the pool. The sand around the spring takes on a circular shape; you could imagine some small sea creature rising out of it. But it’s just water, albeit it very clean water coming out of the ground at what Pullen says is a consistent 46 degrees.

Down the hill from the springhouse is the bottling facility Pullen built after he acquired the property in 2003. It operates on the simple principle of gravity. No pumping. The flow rate is such that the spring yields 3.5 million gallons of water a year, he said. Summit Spring bottles 300,000 gallons a year. (By comparison, Poland Spring bottles 800 million gallons of Maine water annually.)

The Amazon truck arrives every Monday to pick up orders (that $46.57 covers shipping costs as well). Pullen has tried selling it locally, including at Hannaford and Rosemont Market, but Summit Spring water is most readily available through internet sales. How does he reconcile his interest in sustainability with the environmental impacts of shipping water from Maine to regular customers as far away as Hawaii?

“There is always a carbon footprint,” Pullen said. “Unless you grew it in your backyard. But we’re going by gravity.”

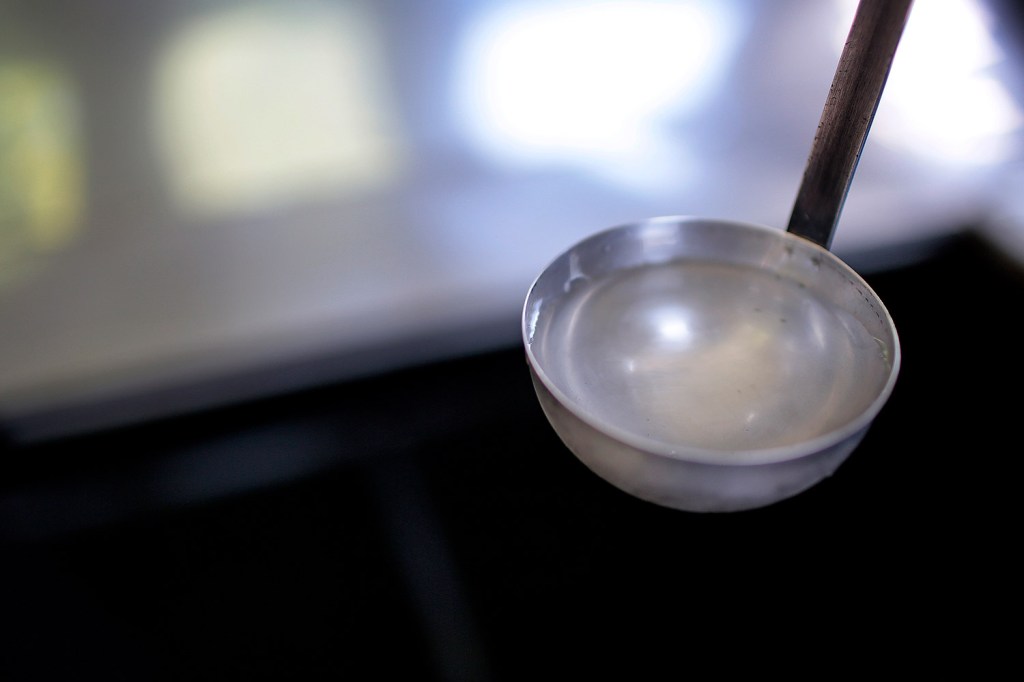

Pullen dipped a stainless steel ladle into the pool and held it out.

“Maine water is the best in the world,” he said. And his is the best of the best, he believes.

TASTE OF THE WILD

This water tastes like nothing and everything simultaneously, empty but satisfying. It’s almost soft. A spokesman for the Maine Drinking Water Program – part of the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention – which regulates bottled-water production, confirmed that Summit Spring water is tested regularly for more than 70 contaminants to ensure it meets the same quality standards as a community water system. But it is untreated, which Pullen is very proud of, considering this a hallmark of its purity.

The Maine Drinking Water Program declined to be interviewed for this article. In an email, Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention spokesman John Martins wrote that no requirement exists in Maine for a water bottler to install treatment. “However, all do except for Summit Spring.”

“This water is the purest thing you’ve ever put in your mouth in your life,” Pullen boasts. It does taste pure, and fresh, in fact so much so that raw doesn’t seem like the right word to brand it with; it sounds too messy and unsettled for something that feels so finished. (Not to mention its association with sewage.)

But raw is the word Pullen likes. And he gets to call it what he likes because this is Pullen’s water, literally. In Maine, rights to groundwater are determined by absolute dominion, i.e, the wishes of the person who owns the land above the water.

He could bottle every ounce that comes out if he wanted. He could drill wells into the aquifer. That’s what Poland Spring, the biggest bottled-water producer in the state and the best-selling brand in America, does to maximize its water production.

Until this point, Pullen hasn’t had the customer demand to warrant expansion.

That could change soon, however. That very morning he met a Pine State Trading Company tractor-trailer that had pulled up to the unmarked gate. The driver was there to pick up a new brand of water coming out of Summit Spring: Tourmaline Spring. Same water, new identity.

POLISHING THE GEM

“I’m my own worst enemy sometimes,” Pullen shrugs. Like when he wanders off on a tangent about how the composition of all surface water in the world changed after the nuclear bomb detonation in Hiroshima. He stops himself after noticing his visitor’s eyes glazing over.

“All of the stuff I am telling you sounds crazy, but it is true,” he said, shaking his head and then redirecting the conversation.

He resents it when Mainers ask him why his water can’t be as cheap, if not cheaper, than Poland Spring. After all, they’ve never heard about it, except from him. He gets irritated when locals ask him to donate water for events, because as he says, in the 12 years he has owned the spring, he has yet to make money from it.

There was that time he went to see executives at Via, the Portland-based advertising agency, and they suggested he consider changing his label from the uber-masculine eagle-on-top-of-a-mountain artwork he’s been using. He was indignant; that eagle pays homage to van Zelm, who introduced it to the brand, and also has a personal connection to Pullen. He said he flew F-15s in the Massachusetts Air National Guard, a plane known as the Eagle. He and Via quickly parted ways. “I walked out,” Pullen said. For a while, Pullen sold his water in a glass bottle wrapped in a brown paper bag. “The Sugar in the Raw people tried to sue me,” he said ruefully.

That was four years ago, but in May, a bottle of the stuff was still on the shelf at the Port Clyde General Store. The price was $6.49 for a liter, which may explain why it was still on the shelf.

Although there is a growing market for “super-premium” high-end domestic bottled water, according to Gary Hemphill, managing director of research for the Beverage Marketing Corporation, it can be challenging to brand.

“After all, water is something that you could, at the end of the day, say is just water,” Hemphill said.

But Pullen has a new partnership with one of Vitalis’ friends, Seth Pruzansky, who approached him about a year ago with an offer to give the water a more distinctly Maine image. They agreed on a rights deal. Pullen would still sell his raw water, Pruzansky and his partners would market the water – the same water – under the label Tourmaline Spring.

Tourmaline is the Maine state stone, and Pruzansky has been hobby mining for tourmaline for years.

“I just said, ‘Bryan, let me brand it in a way that is going to get people’s attention, make them realize this is the state’s true gem,’ ” Pruzansky said. “I believe I can make it a national brand.”

Pruzansky negotiated with Pine State Trading Company, and Tourmaline Spring water is now in 100 stores, Pruzansky said. The subhead on its label is “Sacred Living Water,” and the packaging is biodegradable (it takes at least three years). The branding is definitely more touchy-feely than Pullen’s, but Pruzansky is quick to give Pullen the credit. “I am riding off the back of Summit Spring and what Bryan has done to preserve that source.”

Pruzansky has a background in all-natural marketing, having cofounded the raw foods snack company Living Nutz. He also has had a recent life-changing experience; in 2015 he was released from prison after serving three years of a five-year sentence for marijuana trafficking. “For me it was an extended meditation retreat,” Pruzansky said. “I spent every day of almost three years meditating and really coming to terms with what I had done.… What were the patterns in my life that would cause me to make these decisions?”

He said he’s embarrassed and horrified by the impact his arrest had on his family. His path to redemption? “I just decided I am going to create goodness and do goodness.” He sees his involvement with Summit Spring as part of that “purification” process.

Pruzansky and Pullen are birds of a very different feather, the clean-cut airline pilot with the military background and the reformed hippie with a record. But they are united by their fervent belief in the waters of Summit Spring.

“It is literally like a national treasure,” Pruzansky said.

Before Pullen locks the spring up for the day, he gulps several ladlefuls. How does he survive those multiday trips when he’s flying, after he runs out of the bottled water he brings from home? His gaze is straight, his eyes sincere.

“I suffer,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.