For as long as I can remember, I have been intrigued by the use of the term “the Judeo-Christian ethic” to describe the values and the moral, ethical and spiritual teachings that define American exceptionalism and this nation’s understanding of itself and its mission in the world.

That Jews and Judaism, a community that makes up less than three percent of the American population, can be equated with Christianity, a religion to which the majority of Americans adhere, is nothing less than astonishing. But a close look at the historical record belies this concept. Until very recently, no more than 50 or 60 years ago, there was practically no precedent whatsoever for understanding Judaism and Christianity as sharing a common core of beliefs, practices or morals. It was not until 1952, perhaps with an eye toward the devastating effects of the Holocaust that destroyed more than two-thirds of European Jewry, an event whose consequences he personally witnessed, that President Dwight D. Eisenhower made the concept a part of our national religious vocabulary. In connecting the term with the ideals of the Founding Fathers, he stated that ” ‘All men are endowed by their Creator.’ In other words, our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is. With us, of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with all men created equal.

What Eisenhower did not say was that from its very creation, the U.S. Constitution was denounced by anti-Federalist opponents as a “godless”document. The separation of church and state, so important to the vision of the Founding Fathers, and the role of religion in political life became major issues in the 1860s and 1870s, a period where “Know Nothing” nativist sentiment increased in response to the growth of immigrant populations. The National Reform Association, a coalition formed in 1863 by 11 American Protestant denominations emphasized the “Christian” character of the nation and advocated an amendment to the Constitution that would permanently and officially align the United States with Christianity. Roman Catholics were not included in this effort to “baptize” the American Constitution, and Jews were clearly not a part of this vision.

Although the efforts of the National Reform Association never reached beyond the House Judiciary Committee, where it languished for years, and even though it was periodically reintroduced with no success, the “Christian” character of America was self-understood by large parts of our nation.

For American Jews, a Christian America meant quota restrictions to Ivy League universities, as well as to medical and law schools, jobs that were advertised as “Christian only” and a growing national antipathy that revealed a dislike of Jews at the beginning of World War II only exceeded by negative feelings toward Germany and Japan.

Much of that pronounced anti-Semitism disappeared or went underground in the years after 1945. It became “uncool” to be connected to openly anti-Semitic feelings although Jews were systematically excluded from certain exclusive neighborhoods, summer establishments and private clubs well into the 1960s and beyond. Such restrictions were a part of Maine’s history as well.

But in the early 1960s, a sea change occurred in Christian-Jewish relations, highlighted by the Roman Catholic Church’s Nostra aetate (In Our Time) declaration, promulgated during the Second Vatican Council in 1965. American Catholic bishops were in the forefront of the efforts to remove the charge of deicide, the crucifixion of Jesus by the Jewish people, and the recognition that Judaism maintained an eternal covenant with God, a fact that was denied in the church’s centuries old Adversus Judaeos, its teaching of contempt against Jews and Judaism.

In response, segments of Judaism recognized the legitimacy of Christian scriptures as a means of helping Jews understand themselves in the period after the death of Jesus Christ.

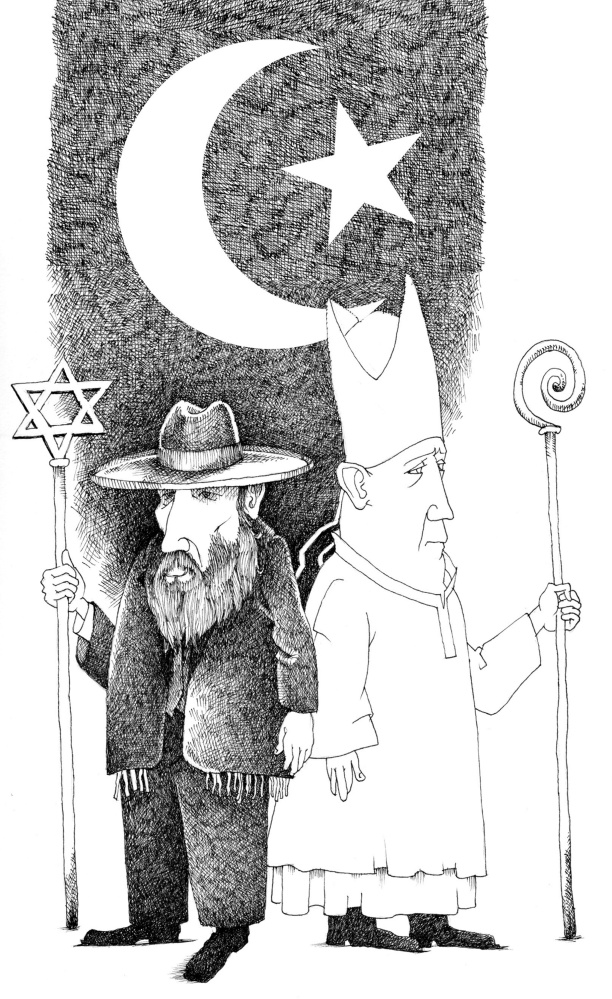

The idea of a Judeo-Christian ethic and the growing importance of interreligious dialogue helped to give credence to a new era of positive relationships between the Christian and Jewish communities.

Then the nation was traumatized by the events of Sept. 11, 2001. A year after this national tragedy, a group of Jews, Christians and Muslims, representing an organization called Interfaith Maine, that was founded in the months before 9/11 (I was one of the co-founders) stood on the grounds of Blaine House, the home of Maine’s then-Gov. Angus King and declared in part that “We are people who worship God, yet we acknowledge and respect our differences; the Jewish people worship God and await the coming of the Messianic age; Christians worship God as revealed in their Savior, Jesus Christ; Muslims worship God and believe Muhammad to be his last prophet.

“We want to send a message of reconciliation to the people of Maine and the world. On the first anniversary of the September 11 tragedy we join together and follow the light of peace. We invite members of all Maine’s faith communities, its political leaders, its educational leaders and all of its residents to join us by signing their names to this declaration.

“We ask the people of Maine, the peace state, to discover their common humanity and to appreciate and to live peacefully and constructively with the profound differences that define the religious pluralism of our nation and our world.”

What I fear is that in the past 15 years since 9/11, the events of our world, highlighted by a heretical radical terrorism that distorts the teachings of Islam, have reshaped the notion of a Judeo-Christian concept to become once again a term of exclusion rather than inclusion. It has become a term that means a belief that the United States can accept Jews into the social contract while Muslims are permanently excluded.

If we are to rely on the religious roots of America as a beacon of freedom, both religiously and politically, should we not offer an equal seat to a religious community that shares the inherited values of Judaism and Christianity while bringing its own set of definitions to the trialogue? How else can the religions grow to understand and respect one another? The Jewish experience in America is a reminder of how an idea so relevant in its implication as a thing of profound faith and understanding can be manipulated for purposes of hate and exclusion.

Expanding the national vocabulary from the Judeo-Christian tradition to the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition is overdue. How else can American Muslims feel a part of the national religious conversation and add to it?

Indeed, isn’t our interreligious table large enough to seat Buddhists, Hindus and Bahais (who are monotheists), among other smaller religious communities, which also bring great spiritual values that include a firm belief in the Golden Rule?

If we can do it in Maine, perhaps that can be the model for a larger national reinterpretation of the religious values we hold dear and that help to guide us through perilous times. After all, don’t we still believe in the maxim “as Maine goes, so goes the nation?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.