Ten years ago, Stephen Conant came to Maine to outline his company’s plans for a multimillion-dollar, high-voltage transmission line that would ship renewable power to Boston. Coursing through an undersea cable from Wiscasset known as the Maine Green Line, the power would be turned on by 2013, said the senior vice president at Anbaric Transmission in Wakefield, Massachusetts.

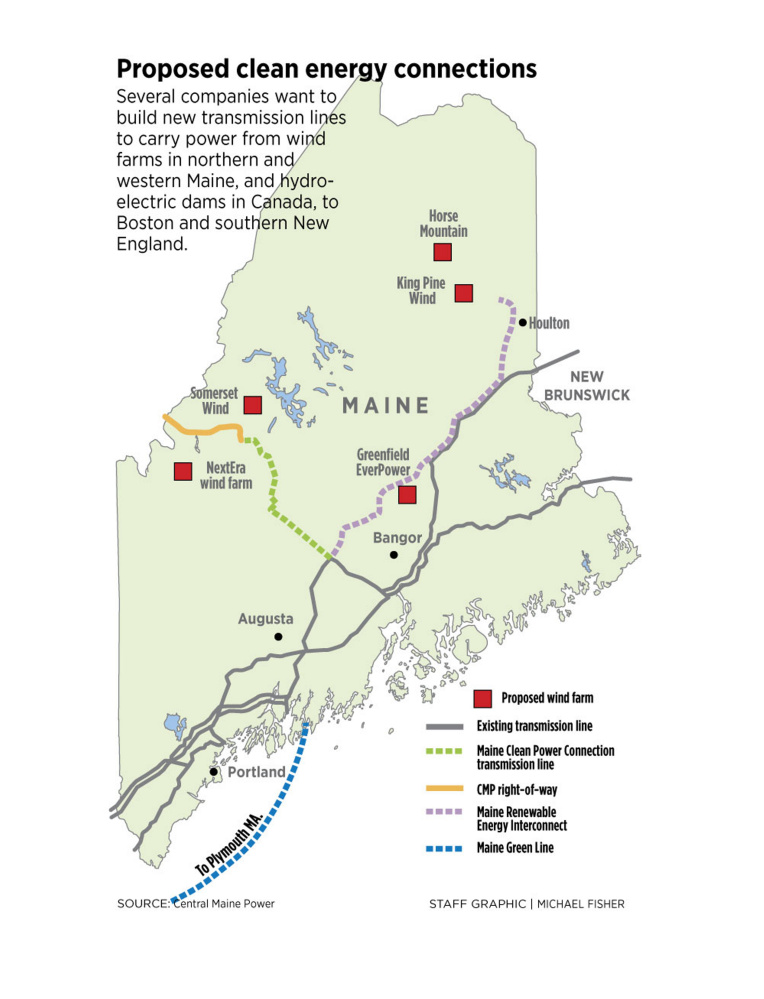

But as 2017 approaches, the Maine Green Line exists only on websites and in PowerPoint presentations. The same is true of 10 or so other transmission ideas that promise to release a flood of renewable energy into southern New England, mostly from wind projects in northern and western Maine and hydroelectric dams in eastern Canada.

A region whose residents and businesses say they want clean, affordable power so far has found it too costly and too divisive to build the transmission lines needed to make it possible.

In October, transmission developers got more bad news. Several big wind and hydro projects, along with the transmission lines that would connect them, were rejected by three southern New England states in a highly anticipated bid competition for long-term clean-energy contracts with their utilities. Passed over were projects that could have brought billions of dollars worth of investment to Maine.

Now Conant and other transmission developers – including the parent companies of Central Maine Power and Emera Maine – are looking to the next opportunity. They’re pinning their hopes on a new and larger bid competition expected this coming April for clean-energy contracts in Massachusetts, part of a sweeping law passed last summer.

“I’m still optimistic,” Conant said recently about the Maine Green Line, which would have initially brought power from a substation at the former Maine Yankee nuclear plant. “There is a policy desire to shift dependence away from fossil fuels. I’m still optimistic we’ll get it done.”

A ‘COLLISION COURSE’

The failure to build new transmission lines for renewable power, after years of trying, is bringing a conflict about New England’s energy future into stark relief.

Many residents and politicians support a transition away from power plants fired by fossil fuels. The problem is, the transmission lines needed to carry renewable energy hundreds of miles, from remote areas where it’s captured to cities where it can be used, are expensive to build and sometimes opposed by people living in their path.

This conflict is playing out across the country. But in New England, there’s a third dimension.

Half of the region’s electricity comes from generators that burn natural gas, supplied by existing lines that are too small on the coldest winter days. Clean energy advocates have largely succeeded in blocking large new gas lines that would tap into the nearby, plentiful shale fields in Pennsylvania. So without more gas lines from the south, or new transmission lines from the north, where will the region’s power supply come from in 10 years?

“We have a demand for power and an opposition to big projects and the cost of them,” said Mark Vannoy, chairman of the of Maine Public Utilities Commission. “Right now, those two things are on a collision course. At some point, something has to give.”

A dozen Maine wind projects have been able to squeeze their power onto existing wires over the past decade, despite opposition from residents who don’t want the massive turbine blades lining forested ridgelines. Together they have a peak generating capacity of around 600 megawatts, enough energy to power more than 100,000 homes. But because they only run when the wind’s blowing, their contribution in New England, which requires 17,000 megawatts on a late fall day, remains quite small.

It’s also possible that small-scale renewable generation – such as solar panels on residential rooftops and solar farms that supply local grids – will reduce the need for big new transmission lines. Many solar advocates see that day coming, as battery technology improves and it becomes more economical to store power onsite.

But for now, developers are proposing far-flung, mega-projects with overall capacities rated in the thousands of megawatts. These include wind farms in Aroostook County and off the coast of Massachusetts, as well as hydro dams in Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador. Hooking them up to the cities will require transmission lines that are long and strong.

TRANSMISSION PUZZLE

Projects that could run through Maine have appealing names:

• The Maine Green Line: It could move up to 1,200 megawatts of Canadian hydro and Aroostook County wind underseas to Greater Boston.

• The Maine Clean Power Connection: This is Central Maine Power’s plan to transmit roughly 550 megawatts of wind from western Maine.

• The Maine Renewable Energy Interconnect: CMP and Emera would team up to link proposed Aroostook County wind farms with the regional electric grid.

CMP recently spent five years on a $1.4 billion upgrade to its aging transmission system through central and southern Maine. But that project was different from these other proposals. It was designed to assure reliable service and keep the lights on. By contrast, no major transmission lines have been built in the region for so-called policy reasons, such as helping states meet mandates to use increasing amounts of renewable energy.

That’s what the New England Clean Energy RFP was all about. Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island requested bids earlier this year for renewable energy projects. They wound up bypassing transmission projects and proposed wind farms that depended on them, including the joint CMP-Emera line that would have given the Number Nine Wind Farm a path south from Aroostook County. The failure to gain that connection contributed to a decision last month for EDP Renewables to temporarily withdraw its application with Maine environmental regulators for the wind farm.

The southern New England states instead mostly chose solar proposals that were closer to home or of a size that could be hooked up to existing wires. The winners included two large solar projects in Maine, part of a package submitted by Ranger Solar of Yarmouth.

The three-state process is confidential. There’s no public scorecard that explains the reason for their choices. But Conant rebuffed a suggestion that perhaps the transmission projects simply cost too much.

“I didn’t see it as an anti-transmission vote,” he said. “I think they were picking the last of the low-hanging fruit. They will need transmission to meet the next, larger goals.”

Conant also pointed out that the winners have a total generating capacity of 461 megawatts. But these solar and wind projects that were picked only produce one-quarter to one-third of their rated capacity, because the output is intermittent. That’s why some of the big transmission projects proposed by Anbaric and others include Canadian hydro in the mix, to back up solar and wind with 24/7 power.

But big transmission lines supported by state-sponsored mandates face another obstacle – opposition from existing power plant owners. They say the cost of building these lines will translate into huge rate hikes for customers.

Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association, has compiled figures to show transmission rates in the region already are five times higher than they were in 2005. During that period, he said, wholesale electric rates have fallen by 48 percent. That drop is tied to the lower cost of natural gas, which is used to generate half the power supplied by members in Dolan’s association.

But the southern New England states don’t want to become even more dependent on natural gas, because prices could rise again and because of their goals of reducing emissions linked to climate change. They have put the brakes on large-scale gas pipeline expansion proposals that would have been subsidized by electric customers, aided by legal action from environmental activists such as the Conservation Law Foundation.

Greg Cunningham, the group’s vice president and clean-energy program director, agreed that the next big jump in renewable energy for the region will depend on at least one new transmission line project. He, too, is looking ahead to the process in Massachusetts this spring.

“I think there are enough transmission projects proposed in northern New England that, given the (renewable energy) commitments in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island, they are going to find a way to make it happen.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.