There is a room in the exhibition “Why Draw? 500 Years of Drawings and Watercolors at Bowdoin College” where the sense of being surrounded by greatness is clear. Centered by a wall of watercolors by Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent and Andrew Wyeth, it opens up with more Homer and Sargent drawings to works by John Marin, the Zorachs, James Smillie and Charles Burchfield.

Smillie might not be a household name, but his 1872 Hudson River School-styled charcoal and white chalk drawing “Yosemite” is an easy thing to appreciate: The artist matches the grandeur of the scene with the boldness of his marks.

The surprise here for me was the Burchfield, one of the handful of artists beloved by the contemporary art audience but with whom I have struggled to find the appeal. His “From Clingman’s Dome, No. 2,” however, erased any doubt in my mind that Burchfield made great art. This watercolor follows a forested mound into the gray horizon like the bow of a ship into a stormy sea. Soaring among patches of blue sky are swirling cumulus clouds, cottony white above but black-tinged with anger below. Ok, Burchfield, you finally got me.

If you step back from the Burchfield, you can see a work by Gustave Courbet – a 19th century giant of realism, but the leading figure of the five or so major artists whose work I have struggled to like – and it might be the most beautiful drawing in a huge and extraordinary show. It’s the head of a man, dark and soft but energized and alive. And it was found at the museum – unattributed – in a box.

“Why Draw?” features an excellent catalog that presents a solid history along with a series of pronouncements and polemics about drawing. But with 150 objects, the exhibition is huge and broad enough to incidentally present dozens of major strands and themes as it follows artistic drawing from the High Renaissance to the present day. The college is uniquely positioned to mount the show: Bowdoin’s collection is the oldest public collection of drawings in America. The first room of “Why Draw?” is lined with work after old master work labeled with an acquisition date of 1811, a collection amassed by college founder James Bowdoin III and his father.

“Portrait of a Man,” by Gustave Courbet, 1870, charcoal and white highlights.

The 1811 works are divided rather equally among Northern European and Italian masters. There are big names among the lot, but the driving force is excellence. This is uncomfortable space for some, since viewers are incidentally but directly challenged with the task of connoisseurship in the overloaded front room. This is where you should be careful: It’s too easy to get caught in the 40 or so works in the front room when there are many more styles and directions in the rooms to follow. If you have a thing for red and black chalk and ancient ink, well, welcome to heaven. Most don’t, however, so you might want to first walk through the entire show so your personal gravity can be your guide instead of the sometimes Sisyphysian slog of chronological history. (That said, curator Joachim Homann is clearly my kind of nerd.)

Rather than laying out any grand reading of “Why Draw?” – which is hard to avoid for any visitor who takes time with this show – the goal here is to list some high points, insights and asides. First of all, with this show, Bowdoin tries to position itself as Colby’s colleague. Bowdoin may be smaller, but it’s one of the best museum buildings in the country and it makes a powerful case for historical heft.

“From Clingman’s Dome, No. 2,” by Charles Ephraim Burchfield, 1915, watercolor over graphite.

One key component is Homer’s watercolor masterpiece “End of the Hunt,” acquired by the museum in 1894, only two years after it was made: It is a rare contemporary acquisition. This work alone is worth the trip: The abstract band of wet watercolor as it sets off the central figure could well be the most glorious passage Homer ever painted. This is not some vague assertion of a passing picture crush. Homer was at his best with watercolor, and we Americans have underestimated his relationship to the British watercolorists because of our macho postwar fixation on oil painting.

In fact, hanging next to “End of the Hunt” is “Marine,” a watercolor Homer painted on the ship during his 1881 crossing to England. The glorious balance between bravado and restraint of the 1892 work is outstripped by the shifting geometrical brilliance of “Marine.” On the swell-tilted deck, we see a figure before us, leaning right to be upright. With an easel-like shape before him, he is the painter. And he is us, the viewer.

The highlights of “Why Draw?” are practically inexhaustable: the great Tiepolo’s 1752 head of young man, William Henry Hunt’s psychedelically detailed 1858 fungi hanging next to exquisite architectural studies by his champion, the critic John Ruskin. John La Farge’s “Meditation of Kuwannon” is a reminder that watercolor is a great painting medium. Mary Cassatt’s bold and orangey 1897 “Barefoot Child” is a local favorite and a statement about the fresh possibilities of powder pastel. Egon Schiele’s 1914 portrait of Friederike Maria Beer is a humanized version of a well-known sitter featuring fine flashes of Schiele’s virtuoso pencil. John Marin’s 1912 Brooklyn Bridge practically quivers with inventive intelligence. George Bellows’ 1920-ish walking woman matches a level of mark-making usually only found in his small Maine coastal oils. As the summer when Marsden Hartley is set to reclaim Maine begins, his Cezannesque still life is a crispy reminder of his engagement with history. Jacob Lawrence’s 1946 Schomburg Library scene features a writing figure of undeniably awkward power. Franz Kline’s 1955 composition sizzles with the exact type of calligraphic virtuosity he sought for his large scale paintings; and Philip Guston’s work of the previous year stands up to it in black and white, a rather unexpected argument for his own abstractions. Christo’s 1976 “Running Fence” is a reminder of the planning aspects of drawing.

Untitled by Franz Kline, 1955, brush and black ink.

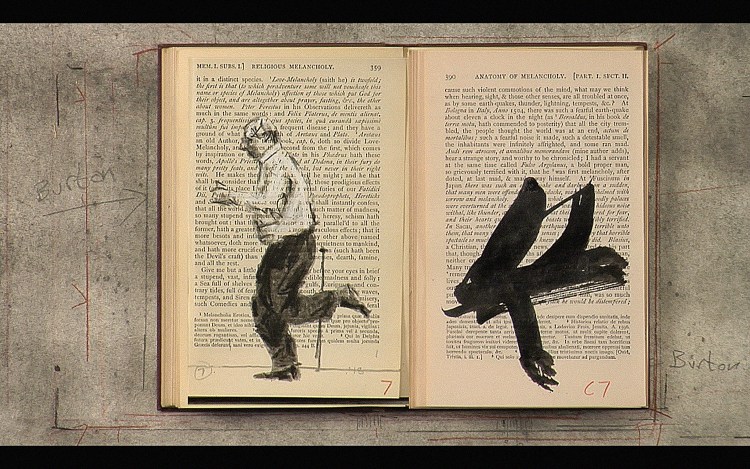

The most exciting work in the show just might be William Kentridge’s boldly hand-drawn in-a-book 2013 “Tango for Page Turning,” Bowdoin’s recent film acquisition shared with several collegial schools.

And this is to leave out strong works by Picasso, Gorky, Klee, Miro, Lachaise, Ossorio, Giacometti, DuBuffet, Matta, Man Ray, Arthur Dove, Anne Ryan, Julio Gonzalez, Henry Moore, Eva Hesse and Lois Dodd, among many other Modernist and Contemporary greats.

There are few disappointments. The front room has too much work and features an unfortunately awkward giant head by Alex Katz. In a way, it’s hilariously apt, but it gets pulled down hard the moment you notice the old master marks all around it. And as the show starts with some drier works on the left side (and the Katz wall) of the front room, it ends with a suite of works by Natalie Frank. It’s a potentially interesting series based on the Brothers Grimm’s story of a young woman who escapes her father’s sexual advances only to be rewarded by having the devil cut off her hands. Here, however, Frank’s unmediated touch and unrestrained color don’t hold up at the end of the soaring standards set by the first 130 works.

“Why Draw?” is vast and exciting, so set aside several hours and be prepared to find your own conclusions, questions and conversations. The possibilities are endless.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.