AUGUSTA — Linda Baldwin doesn’t need anyone to teach her about poverty; she’s living it. For as long as she can remember, she has worked hard and struggled for a living, as had her family before her.

As a child, Baldwin, 59, watched her mother take in other people’s ironing for a little extra cash. When the Gardiner woman had children of her own, she worked multiple jobs to cover her bills, often skipping meals so her children could eat.

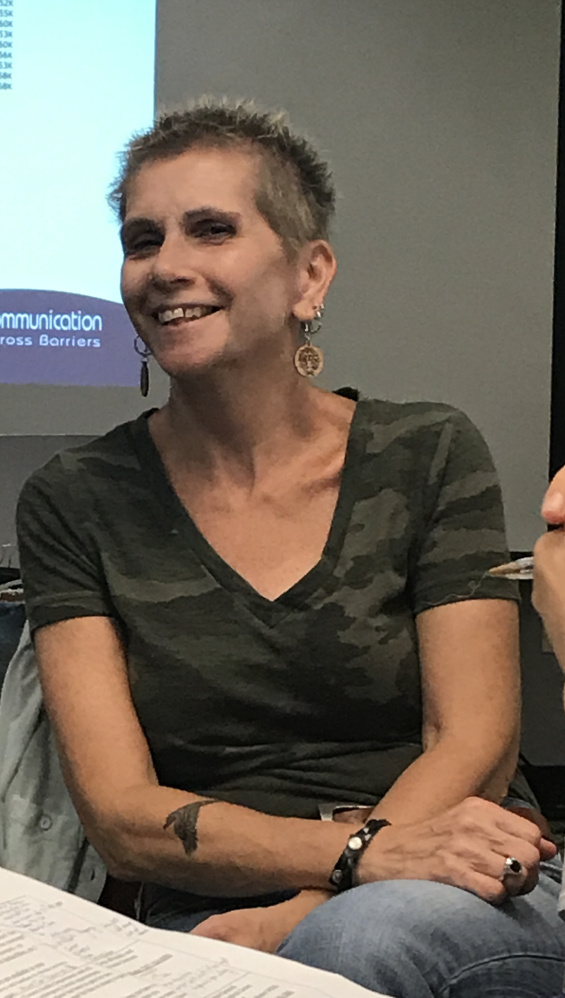

Yet there she was on Tuesday in a carpeted conference room in the Augusta Civic Center, attending a two-day seminar run by Donna Beegle, an expert who travels the country training government officials, educators and service providers on how to best serve people in what she describes as “the war zone of poverty.”

Beegle herself grew up in deep poverty in Arizona in a family of migrant agricultural workers who had, for generations, struggled for food, clothing and shelter. Today Beegle educates others about the true causes and consequences of poverty, the various forms it takes and its devastating toll on the people living in it.

After years of suffering the daily heartbreaks and routine indignities of a life of poverty in the U.S., Baldwin and Beegle have each come to similar conclusions about what must happen to combat it. People must be more “poverty-competent,” as Beegle says, in order to dispel the cultural myths and stereotypes about poverty that help perpetuate it.

“I feel like we really need to change the attitude about poverty and the language that we use,” Baldwin said. “When that happens, I think we’ll really be able to make changes.”

It’s an idea that is taking root in Maine, in no small part because of Beegle’s work. This week marks her sixth visit to the state, where she has worked in communities from Machias to Farmington to help providers and people in poverty forge more trusting and productive relationships.

At the heart of Beegle’s outlook is a deep empathy for others, those in poverty, those working in the field, and even those ignorant about poverty and its causes. She starts with a simple premise, that there is no comprehensive poverty education in the U.S., and without a deep understanding of the nuances and complexities of poverty and its effects, even good faith efforts to address it can be hampered.

Through that lens she has come to see even the worst misconceptions about poverty as learning opportunities. In her opening remarks Tuesday, Beegle talked about listening to a radio host expound on the true cause of poverty. His conclusion? That poverty was a choice and people who lived in it wanted to.

“I want to help him,” Beegle said to the astonished gathering.

If Beegle seems preternaturally tolerant, it’s because she knows from experience, research and work in the field that judgment is a nonstarter in relationship building. So instead of focusing on the individual, Beegle looks at the circumstances that helped shape a person’s worldview. Without education, she reasons, how can we expect people to know any better?

ROLE PLAY AND REFLECTION

In her seminars too, Beegle focuses on lived experience. Many of the exercises attendees perform involve role play or reflection that provides deep and sometimes painful recognition of the cyclical and systemic nature of poverty.

In one exercise, Beegle has all of the conference attendees line up in a row. “This is you under the age of 18,” she tells them. Then she asks anyone with a mother who received a bachelor’s degree to take a few steps forward. If father or grandparents also completed college, take a few more steps.

But if you were ever evicted, she says, take a few steps back. If you had your utilities shut off, a few steps more. Soon enough the staggered line begins to reflect the spectrum of social class in the room and, in a visual and visceral way, the extent to which some people, through no doing of their own, had a head start on others.

It’s not that Beegle wants people to feel ashamed of their upbringing or their privileges. Instead, she wants them to recognize how circumstances completely out of their control set them up for greater or lesser access to opportunity and success.

“That’s really what this institute is all about,” Beegle said in an interview. “Let’s immerse in this subject. Let’s walk the walk of what people are experiencing so you’re not only intellectualizing it and understanding the history of poverty, the labels we’ve used to describe people, the facts about poverty, but you are feeling how poverty steals hope.”

At the end of the exercise, Beegle reminds everyone that this line represents only a small slice of economic inequality in the U.S., where 1 percent of the population owns up to 40 percent of the country’s wealth.

In another exercise, Beegle asks the group to figure out which bills to pay on a limited income. At the end, no one had paid for health insurance. Most chose not to buy diapers, assuming they could find them somewhere else. A large contingent chose to pay only part of their rent.

Beegle relayed the story of a woman she met in Texas who was struggling to get out of poverty. The woman had gone through one of Beegle’s programs and cried as she described how for the first time in six years she was able to cover her rent after receiving help to set up an ironing business.

Asked why she was crying, the woman said, “Well, there are other women who can’t pay their rent.” Asked why that was so upsetting, she said, “Our owner of our apartments, the only way he’ll take partial rent is if you do sexual favors for him.”

Turning to the group, Beegle asked how many would still choose to pay only part of their rent. No one volunteered.

For Beegle, cultivating this kind of awareness about other people’s burdens is the first step in addressing the systemic causes and consequences of poverty in a more humane and humanizing way. Once people can meet each other as fellow human beings, free of preconceived notions about one another, she says, they can more effectively work together.

THINKING ABOUT POVERTY

In Baldwin’s experience, Beegle’s work is absolutely necessary. She can remember, in painful detail, moments of deep humiliation at the hands of social service case workers and unseen moments of despair as she struggled to support her children.

Once, Baldwin recalled, she went looking for information on General Assistance benefits. After waiting for what felt like an eternity, she was called in to speak with a woman who proceeded to grill her on the most intimate details of her life. What kind of tampons did she use? Was she sleeping around with men she didn’t know?

“I remember very clearly her looking at me and saying, ‘I know how you women are,’ ” Baldwin said. “I also remember telling her to ‘go to hell.’ ” What the woman didn’t know was how hard Baldwin was already working to support her young children. In one attempt, Baldwin remembered, she took multiple jobs cleaning apartments to get them ready for new tenants. She could not afford child care so she would bring her two toddlers with her, setting them up with a blanket and toys while she cleaned.

Then one day she arrived at an apartment in complete disrepair. When they walked in the door, Baldwin and her children were greeted by air thick with the smell of urine and lingering smoke.

“I can still see my beautiful, blond-haired, happy children playing in the middle of the dirtiest environment they had ever been in,” Baldwin said. “I cried the whole time, trying to hurry.”

Had the caseworker been better educated, Beegle believes, she may have treated Baldwin with more respect and done more to help her. It’s a belief born of her own experiences growing up feeling like no one cared about her or her family’s struggles, then learning that many people did care but didn’t have a clue what to do about it.

After teaching people how to think about poverty, Beegle moves on to the actions they can take. She is currently working with 20 communities across 12 states to set up Opportunity Community Models, which connect existing networks of law enforcement, education and social service providers in an effort to provide more comprehensive support to people living in poverty.

Franklin County is the first community in Maine to adopt the model. Earlier this year, participants in the program celebrated their first batch of trained poverty navigators and participating “neighbors,” or people in poverty.

Beegle was back in Maine this week to pilot a new program called “If not me, then who?” that emphasizes every individual’s responsibility to help people in poverty, regardless of their role.

“Every person can make a difference,” Beegle said. “Every person can leave people in a better place than they find them.”

Kate McCormick can be contacted at 861-9218 or at:

kmccormick@centralmaine.com

Twitter: KateRMcCormick

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.