You might think “Confabulations of Millenia” is an ostentatiously fancy title for a show of art about craft. You would be right. And that’s precisely why it’s an apt title.

“Confabulations” is a particularly worthy show about the intersection of historical decorative arts with current contemporary art. The decorative arts as they appear in this exhibit at Portland’s Institute of Contemporary Art are really “les art decoratifs” with a clear and deep – however impure – dedication to European aesthetic programs of centuries past.

This is only reinforced by the pair of old-school paintings by Melora Kuhn – “Banished” and “Neuschwanstein” – which fall painfully short of the otherwise stellar level of craftsmanship throughout the show, including Kuhn’s witty pair of porcelain busts on which she has transferred images in blue to reference their conflicted status as china – as in her “Delft Bust.”

Similarly, Oscar Sancho Nin’s acrylic on canvas “Monarch” has a one-of-these-things-is-not-like-the-others feel aside from its decorative guilded frame. But here, Nin’s skill echoes Francis Bacon’s expressionistic versions of past paintings sufficiently to activate the Pop Art game at the foundation of “Confabulations.”

“Confabulations” was curated by New York textile artist Richard Saja who is also treated to his own mini retrospective in the ICA’s handsome side gallery. “Historically Inaccurate” features Saja’s bad-boy embroidery on traditional French toile. But even this requires a bit of explanation. “Toile” means “cloth” or “canvas” in French. In an art context, “toile” would be taken as artist’s canvas. In a fashion or decorative context, “toile” implies the patterned French cotton fabric “toile de Jouy,” which came to popularity in the 1760s. Saja embroiders on traditional toile, generally taking the images in flip directions one might assume from a bored college teenager drawing in his art history book – adding, for example the anti-Trump symbol of “45” with a line through it into an otherwise idyllic scene. To be sure, Saja can handle a needle, but even when he piles on his skill, it still pales in the shadow of his Rococo antecedents. And let’s not fool ourselves, Saja is piling onto the toile prints’ fascination with risqué Rococo works like Fragonard’s seminal (and supremely saucy) “The Swing” of 1767 in which a young man swings his lover with the occasion, perhaps, to glance up her skirt. Saja reminds us that while Rococo might not have been avant-garde, echoed as it was in toile de Jouy, it was Pop Art avant la lettre. And this is no smugly simple insight; it’s a reminder that the relationship between fine arts and popular culture has been of critical/philosophical interest since the waking moments of the Enlightenment. (For my art history nerds out there, Saja credibly hints that Modernism was visible with the popular culture reception of Rococo.)

While Saja’s work offers depth (and a few refreshingly Pop Art phrasings of juvenile wit), much of the work by the other 18 artists appears with more immediate content. Jeremy Hatch’s “Accident,” for example, features a wet-pantsed porcelain cherub with a puddle of gold luster pooling as pee. It’s an inglorious play, not only on the materials, but the famous “Manneken Pis” of Brussels, a sculpted cherub that would pee beer during festivals.

Martha Arquero’s “Pop Figures” use traditional Native American (Cochiti?) pottery styles but to render Mickey Mouse, Spiderman and Pokemon figures, hinting at what comic strangeness, wit and irony the original works might have conveyed to their owners and admirers. And while Arquero’s figurines might seem to throw off the Eurocentric strand of decorative arts, in fact, they reel it in with a needed nod to cultural imperialism and even a wisp of border culture logic. Mexican culture, after all, is currently under fire from the White House, but it is a complex culture that runs deep with ancient indigenous religions, Catholicism, regional aesthetics and a varied blend of cultures. Arquero’s works strike me as a very specific type of “Southwest” pottery as it would honestly meet the modern world: In other words (and please note that I know nothing about her intentions), the irony of including Arquero’s work is that there is nothing at all ironic about it.

Beth Katleman’s “Hostile Nature, USA” is a brilliantly titled work that looks like a Baroque decorative wall one would expect to find at, say, Versailles. It features porcelain figures and elements presented on robin’s egg blue painted rectangle on the wall. Only, instead of classical imagery or genre morality scenes, we get a dose of American moral surrealism. A girl with a tennis racket un-idyllically swats at birds, for example, in what should be a scene of pastoral tranquility.

Douglas Goldberg’s sculptures – gorgeously sculpted drapery tossed over modern objects like microphones and nightlights – also pose a challenge to the viewer in a stunningly humble gesture by the artist: Goldberg rather clearly acknowledges that pretty much any classical sculptor blew the technical doors off the sculptors of today. Rendering drapery was a basic ability for all sculptors past, and now it has become a rarity. Goldberg doubles down on his own wit by obviously hiding his subject in plain sight – and announcing this even with his titles. We don’t see a microphone in “Microphone,” for example. We see gorgeously sculpted drapery shaped like a handkerchief thrown over a microphone on a stand mounted on a podium played by a pedestal. This is a witty bit of theatricality that slickly brings the actual pedestal into the installation. But even beyond that theatrical wit is a nod to the modernist sculptural brilliance of Anthony Caro. Goldberg’s alabaster drapery hangs over the edge of the pedestal. It’s a table-top piece that must be displayed at a table’s edge. Goldberg’s material humility bubbles up through his conceptual vigor and craft virtuosity, but he still manages to give a nod to the formal intelligence of modernist sculpture.

Kehinde Wiley’s “Penitent Mary Magdalene” is a searing disappointment. Wiley was selected to paint President Obama’s official portrait for the National Portrait Gallery, and it is his painterly precision that drives his work. But “Confabulations” merely presents a digital print of one of his paintings – a young black male doubled up in costume and pose overdeterminded by hip-hop clichés and the rhetorically iconographic gestures of the reformed prostitute (Magdalene) around whom floats a field of decorative wallpaper-ish yellow flowers. Wiley’s paintings generally convey a disquieting power, and I imagine the original of this work does too. But “Magdalene” is like serving a picture of cupcakes to real people as their dessert. It’s saccharine without substance. Nonetheless, it tantalizes. Conceptually, and maybe even ideologically, that’s a good thing.

Livia Marin’s “Nomad Patterns” series porcelain cups brilliantly spill their decorative content rather than expected liquid contents. Oh, that we could lap it up – and, visually, we do. The transitive quality of the Delft styling is echoed in Kuhn’s nearby Delft-decorated porcelain busts.

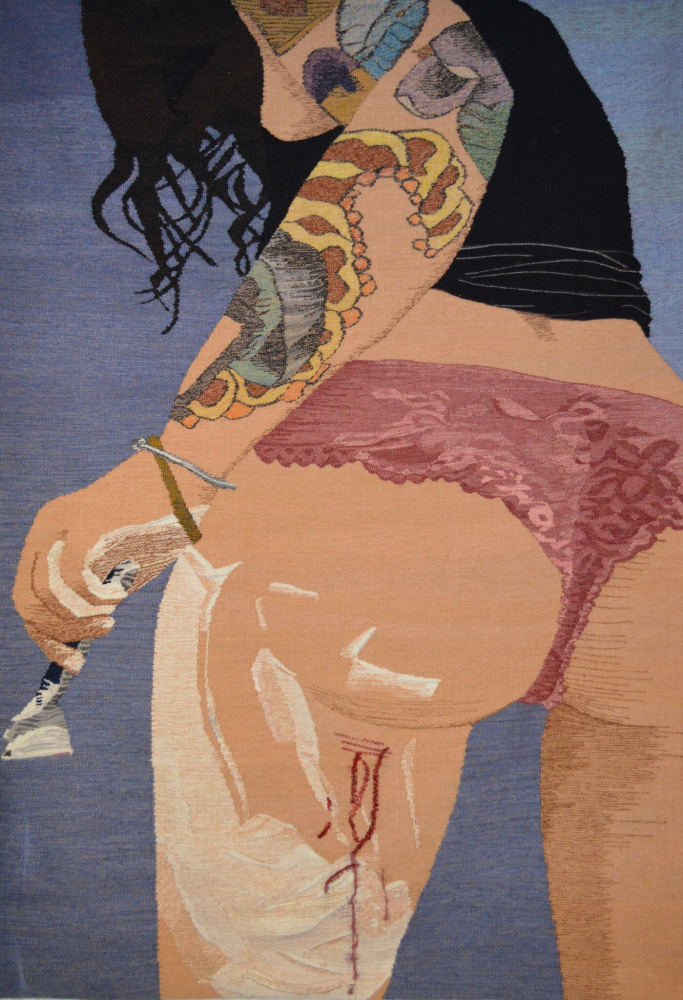

Grandly greeting visitors visually to the ICA’s grand Lunder Gallery, Erin Riley’s tapestries monumentalize ephemeral moments, such as a woman prepping for a 4 a.m. hookup call – a fleeting sexual encounter. We see the figure from the rather insouciant porn-like perspective of looking up towards her lingerie-covered buttocks while she is shaving, the act which has opened a bleeding nick on the back of her upper thigh. We can imagine the image might have been taken as a selfie so that the shaver could better survey the minor cut – a throwaway image of an unintended trace of removing unwanted sexual markers like body hair. Maybe the combination of the grandeur of the medium with the debased subject will be too much for some, but the real content is the subjectivity of the image. Most viewers won’t know that tapestry in its time was more highly valued than painting. Others will see the action as a woman in private at her toilet. Others still will use the distraction as an excuse to take a long, hard and clear look at her impressive behind. With distance – well offered by the installation – we can sense this entire range.

And that is the great accomplishment of “Confabulations”: It offers enough context and distance for us to see and sense the scales that hold the decorative arts and contemporary work in a sort of conceptual balance. What at first might look like a conceptual mess, comes quickly clean into surprisingly succinct focus. What makes it easy and enjoyable is that Saja isn’t insisting on some specific philosophical polemic. He’s merely pointing to current aesthetic conversations between contemporary studio practice and older traditions of decorative arts. What you make of those conversations is up to you.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.