When life gets rough, and incivility and cheap competitiveness seem to be the order of the day, it’s nice to imagine there might be a hidden refuge where politeness and sense of community are encouraged and people work to excel for the benefit of their compatriots, rather than only for themselves.

That’s the appeal of Karen Crouse’s “Norwich,” a non-fiction portrait of a small New England town where all children are encouraged to pursue the sports they enjoy, and the quest for Olympic gold is supported as a reasonable ambition. Norwich has produced 11 or 12 Olympians, depending on how you count. (Snowboarder Kevin Pearce sustained a career-ending brain injury a month before he would have departed for the 2010 Winter Olympics.)

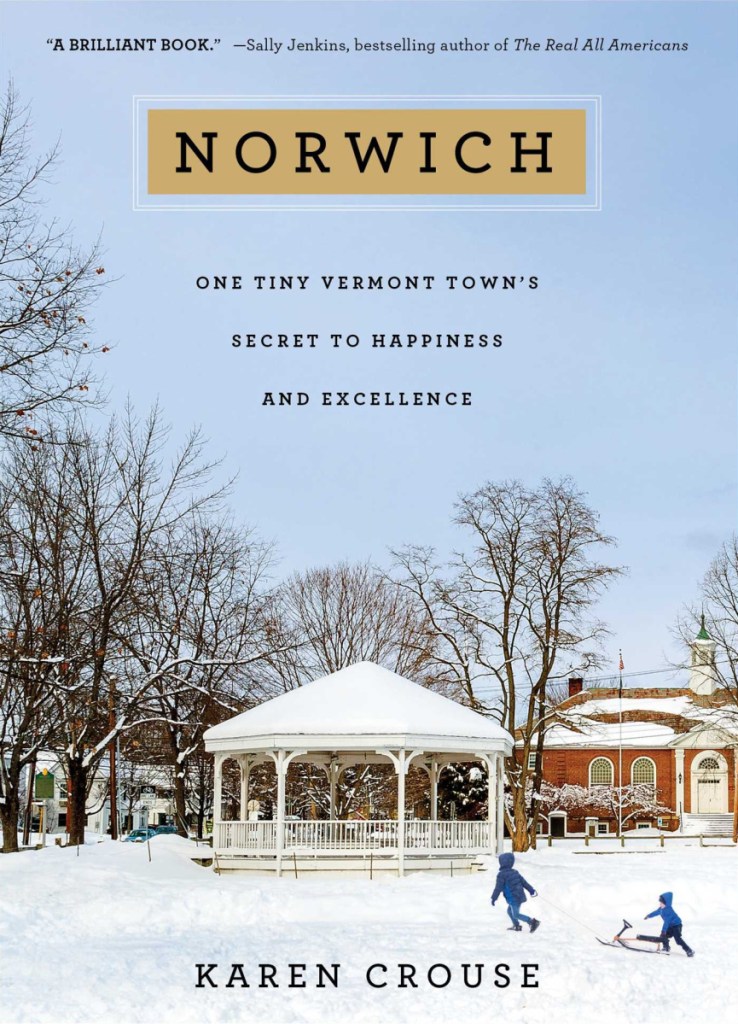

With approximately 3,000 residents, Norwich, Vermont, has sent an athlete to nearly every Winter Olympics in the past 30 years. Three Norwich athletes have brought home medals. New York Times sportswriter Karen Crouse wanted to know what the town is doing to attain such success, and talked to students, teachers, parents and coaches to see whether they could articulate the magic formula that seems to have seeped into the drinking water.

Crouse writes, “The well water in Norwich is perfectly delicious, but the town’s outsize success in Olympic sports has more to do with the way it collectively rears its children, helping them succeed without causing burnout or compromising their future happiness. It’s how harried parents across America would like to bring up their children if not for the tiger moms and eagle dads in their midst.”

Founded in 1761 as a farm community, Norwich is located two miles from Hanover, New Hampshire, and Dartmouth College. Described by a local columnist as “Disney World with maple trees,” the town is mostly white and middle-class, its residents enjoying median household incomes of $89,000. Although many families aren’t affluent, many have plenty of disposable income to be spent on sports equipment, travel and training. Kids from families of lesser means often do receive assistance.

Crouse structures “Norwich” around six chapters that each focuses primarily on one Olympic athlete and one lesson to be learned from his or her story (e.g. “Teach Your Parents Well”).

The first Norwich Olympian Crouse profiles is also perhaps the saddest: Alpine skier Betsy Snite, who with her younger sister, Sunny, endured the constant attention and ceaseless micromanaging of their father, Albert O. Snite, whose diabetes prevented his own participation in sports. The Snite girls’ tale is a cautionary one. Betsy won a silver medal in 1960, but at a cost. She and Sunny were estranged for many years, and Betsy died of lung cancer at age 45.

The friendship of ski jumpers Mike Holland and Jeff Hastings offers a happier example of the spell Norwich can cast. Ten-year-old Holland got his start in the sport with hand-me-down equipment supplied by Hastings. The boys would eventually both go on to compete in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, and the residents of Norwich organized a heartfelt send-off that would become a tradition for nearly every Olympian from the town.

The town also rallied for those athletes who felt they had let everybody down by not bringing home gold. Moguls skier Hannah Kearney felt she hadn’t performed up to her potential when she won a bronze medal at Sochi, but the town nevertheless organized a homecoming celebration to cheer her up.

Perhaps the most moving story is that of Kevin Pearce, who qualified for the 2010 Winter games, only to have his life changed irrevocably in the wake of massive head trauma sustained when he attempted a variation on a twisting double backflip and slammed his forehead on the edge

of the half-pipe structure. Norwichians rallied around him, providing some of the strength he needed to put his life back together and become an advocate for survivors of brain trauma. Seven hundred and twelve days after his accident, Pearce returned to his snowboard.

Crouse, who has covered nine Olympic games, sells the specialness of Norwich a little harder than necessary, but she makes it easy to see why she is so enamored with the place. She unearths anecdotes that illuminate the best principles of sportsmanship and neighborliness and writes, “The residents look out for one another, and their connectivity provides a social safety net that no amount of money can buy.” The book touches on some complicated issues about competition, ambition and grace.

Crouse wraps up “Norwich” with some autobiographical details about her youth in California. Inspired by the record-breaking success of Mark Spitz at the 1972 Munich Olympics, she took up competitive swimming at the Santa Clara Swim Club. She never came near to being an Olympian, but she tells of how an encounter with one coach led her to want “grow up to tell people’s stories for a living.”

Crouse acknowledges that Norwich’s success isn’t easily replicated. She writes, “… it takes people with time, money or expertise to give freely to fund athletic programs, to find facilities and to create facsimiles if none exist in towns less blessed than Norwich with its nearby Ivy League campus or Santa Clara with its three-pool swimming facility.”

What isn’t clear from “Norwich” is how the gung-ho attitude toward sports affects kids who simply aren’t that interested in athletics. Assuming there are such individuals in Norwich, how much support do they get from their fellow townspeople to pursue their interests in literature or the arts, for example?

Crouse argues that the lessons she has gleaned from Norwich point toward a more humane philosophy of athleticism and of child-rearing, one in which the kids choose their interests and compete on their own terms. She makes her case through thorough and insightful reporting, delivered in an authoritative and engaging style.

With passion, humor and elegance, Crouse’s “Norwich” celebrates the good in people, athletes or not. Her book provides a welcome beacon of light in a time of wintery darkness.

Berkeley writer Michael Berry is a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, native who has contributed to Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, New Hampshire Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and many other publications. He can be contacted at:

mikeberry@mindspring.com

Twitter: mlberry

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.